Are We in a Recession?

Former President Bill Clinton recently said that the U.S. economy is already in a recession. I view that as more of a political statement rather than an economic one, but let’s explore the question, “Is the U.S. economy currently in a recession?”

The frustrating answer is: we don’t know. To be more scientific, we can say that there’s currently no solid evidence that the U.S. economy is either in a recession or about to go into a recession. Obviously, that can quickly change.

In the most-recent CWS Market Review, I wrote that Wall Street has been paring back its forecasts for Q2 GDP: “Goldman lowered their GDP growth forecast from 1.8% to 1.6%. Morgan Stanley lowered theirs from 2% to 1.8%. JPM dropped theirs to 2% from 2.5%, and BofA Merrill went from 2.4% to 1.9%.” The catalyst was the poor retail sales report.

Let me make a few points. By recession, we mean that the real GDP is actually receding. As in, it’s getting smaller. Oftentimes, people will say that a bad but growing economy is in a recession. Yet we want to stick to the technical definition.

The commonly accepted standard for dating recession comes from the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER). The media often says that an official recession is two or more consecutive quarters of negative real GDP growth. That’s not correct. This is what NBER looks at when deciding if the economy is expanding or receding:

The Committee does not have a fixed definition of economic activity. It examines and compares the behavior of various measures of broad activity: real GDP measured on the product and income sides, economy-wide employment, and real income. The Committee also may consider indicators that do not cover the entire economy, such as real sales and the Federal Reserve’s index of industrial production (IP). The Committee’s use of these indicators in conjunction with the broad measures recognizes the issue of double-counting of sectors included in both those indicators and the broad measures. Still, a well-defined peak or trough in real sales or IP might help to determine the overall peak or trough dates, particularly if the economy-wide indicators are in conflict or do not have well-defined peaks or troughs.

So the keys are real GDP, employment and income, and we also want to look at sales and industrial production. The problem with looking at the entire economy is that the GDP data series is quarterly. In a perfect world, it would be monthly and highly accurate. Since it’s not, we have to rely on the other indicators listed by NBER.

Recessions and expansions tend to be symmetrical, meaning a sharp recession often leads to a sharp recovery. Shallow recessions lead to shallow recoveries. This time around is different—a sharp recession has led to a very mediocre recovery.

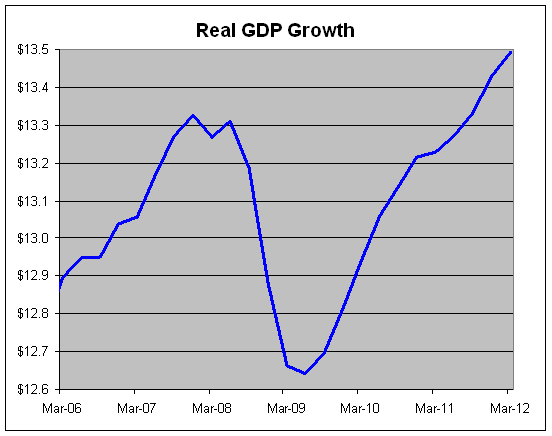

Keeping with NBER’s methodology, let’s first look at real GDP.

During the recession, real GDP fell for four quarters in a row, and for five out of six. We then had one mildly positive quarter followed by three goods ones. Since then, however, we’ve had very tepid growth. The last seven quarters have averaged less than 2% growth which isn’t enough to push down the unemployment rate. Growth for Q1 came in at just 1.9%.

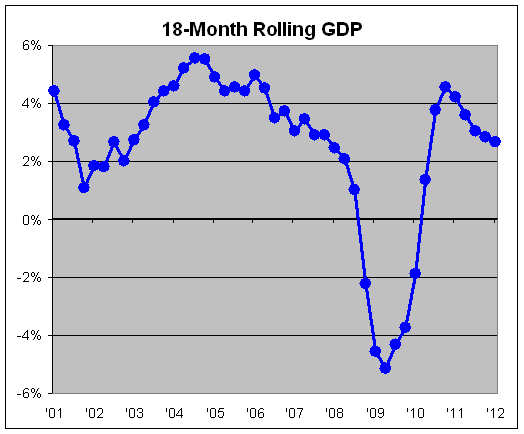

Interestingly we can see the clearest evidence for a trend by looking at real GDP over the trailing six quarters.

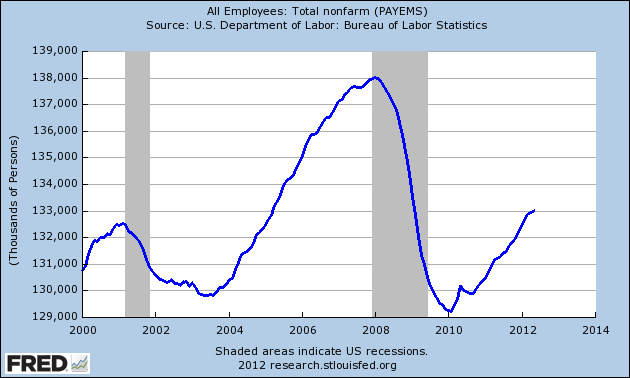

Now let’s look at another NBER factor: economy-wide employment. These are the seasonally adjusted non-farm payroll numbers.

What stands out is the marked contrast between GDP and employment. GDP has already surpassed its peak from before the recession. But we’ve made back less than half the jobs lost during the recession. Moreover, the rate of job gains is slowing. Last month, the economy created just 69,000 jobs. Nearly nine million were lost during the recession. Employment is clearly the weakest part of the economy.

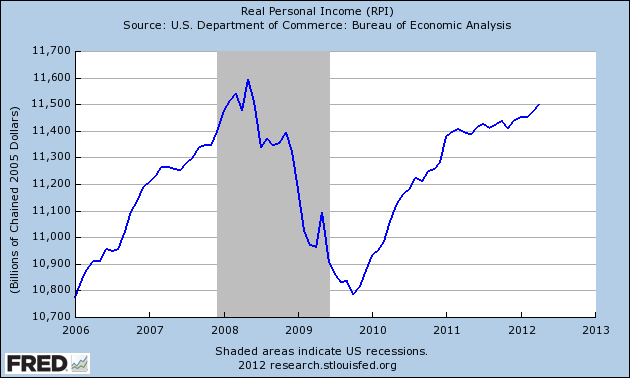

Here’s real personal income. We can see signs of a recovery but the trend dramatically slowed down starting at the beginning of 2011. There’s been a slight uptick recently, but it’s nowhere near the growth rate we saw in 2010.

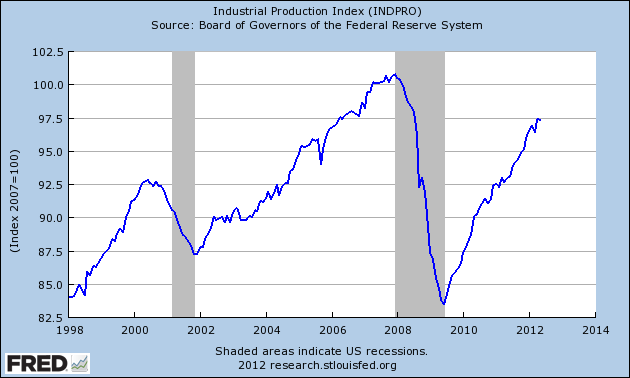

If I wanted to see signs of the economy slowing down, I’d expect to see a sharp drop in industrial production. Notice how IP slowed down before the 2001 recession began. Except for a few bumps, IP has climbed pretty steadily since 2009.

The May IP report showed an unexpected decline of 0.1%. This is probably the clearest sign that the economy may soon be in trouble. But we’ll need to see more data to confirm a trend.

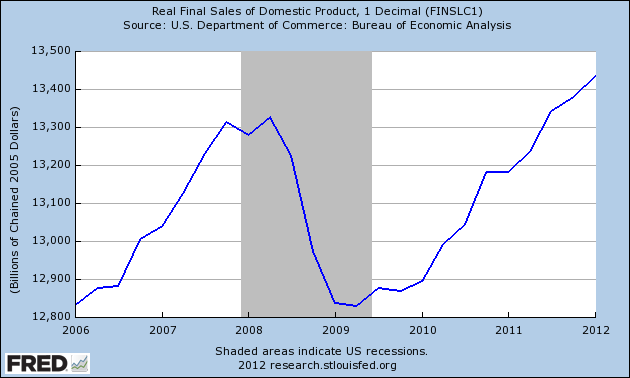

Finally, here’s a look at real sales which is probably the strongest variable. There doesn’t seem to be any visible drop-off yet.

Posted by Eddy Elfenbein on June 18th, 2012 at 11:16 am

The information in this blog post represents my own opinions and does not contain a recommendation for any particular security or investment. I or my affiliates may hold positions or other interests in securities mentioned in the Blog, please see my Disclaimer page for my full disclaimer.

-

-

Archives

- June 2025

- May 2025

- April 2025

- March 2025

- February 2025

- January 2025

- December 2024

- November 2024

- October 2024

- September 2024

- August 2024

- July 2024

- June 2024

- May 2024

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- July 2019

- June 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- May 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- July 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- March 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- July 2016

- June 2016

- May 2016

- April 2016

- March 2016

- February 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- July 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- April 2015

- March 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- December 2014

- November 2014

- October 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

- July 2014

- June 2014

- May 2014

- April 2014

- March 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- July 2013

- June 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- August 2012

- July 2012

- June 2012

- May 2012

- April 2012

- March 2012

- February 2012

- January 2012

- December 2011

- November 2011

- October 2011

- September 2011

- August 2011

- July 2011

- June 2011

- May 2011

- April 2011

- March 2011

- February 2011

- January 2011

- December 2010

- November 2010

- October 2010

- September 2010

- August 2010

- July 2010

- June 2010

- May 2010

- April 2010

- March 2010

- February 2010

- January 2010

- December 2009

- November 2009

- October 2009

- September 2009

- August 2009

- July 2009

- June 2009

- May 2009

- April 2009

- March 2009

- February 2009

- January 2009

- December 2008

- November 2008

- October 2008

- September 2008

- August 2008

- July 2008

- June 2008

- May 2008

- April 2008

- March 2008

- February 2008

- January 2008

- December 2007

- November 2007

- October 2007

- September 2007

- August 2007

- July 2007

- June 2007

- May 2007

- April 2007

- March 2007

- February 2007

- January 2007

- December 2006

- November 2006

- October 2006

- September 2006

- August 2006

- July 2006

- June 2006

- May 2006

- April 2006

- March 2006

- February 2006

- January 2006

- December 2005

- November 2005

- October 2005

- September 2005

- August 2005

- July 2005

Eddy Elfenbein is a Washington, DC-based speaker, portfolio manager and editor of the blog Crossing Wall Street. His

Eddy Elfenbein is a Washington, DC-based speaker, portfolio manager and editor of the blog Crossing Wall Street. His