The Disaster Of Confederate Monetary Policy

I won’t weigh in on the controversy surrounding the Confederate flag. But if you’re not persuaded by insurrection or slavery, at least consider the disaster that was Confederate monetary policy.

Wars are expensive things and the Confederacy had trouble raising revenue with taxes; nor could they borrow effectively in the international bond market. So CSA Treasury Secretary Christopher Memminger turned to an old stand-by — the printing press.

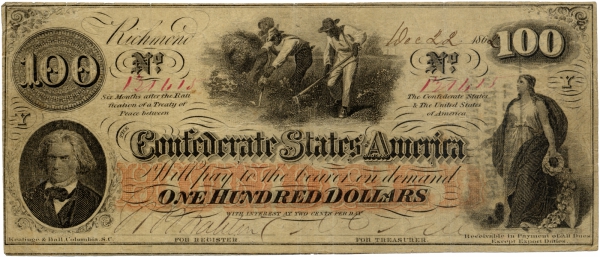

With no other avenue open, Secretary Memminger reluctantly turned to the printing press to meet the Confederacy’s financing needs. Memminger was aware that such a move would likely cause a rise in the price level and warned the government repeatedly about this danger, to no avail. The Treasury bills issued during the war had a peculiar feature: They were redeemable for gold two years after the war ended, which meant that the value of the bills was partially tied to expectations of victory for the Confederacy. So rapid was the expansion of the Confederate money supply that at one point during the war, the orders for new currency exceeded the printing capacity of the Treasury’s presses. To fill the order, the Treasury began to accept counterfeit currency as valid to further expand the supply of money.

The enormous increase in the quantity of currency precipitated an era of hyperinflation in the Confederacy as more dollars chased fewer goods. The price level in the South rose by roughly 10 percent per month during the conflict and by the end of the war, the price level had increased in the Confederacy by a factor of 92, though imports tended to inflate more quickly and exports more slowly. At the same time, the blockade, military destruction, and the loss of workers to the war caused real wages and output to fall dramatically, with per-capita consumption falling by 50 percent in real terms. Indeed, if banks had not sharply increased their reserve ratios for fear of bank runs, the inflation created by excess money in the South would likely have been even more severe.

Hyperinflation had a number of negative effects on the Southern wartime economy. As currency became useless as a store of value, the rate at which people spent their cash reserves — the velocity of money — increased, driving prices still higher. In many areas of the South, Confederate dollars became worthless unless accompanied by some valuable underlying commodity such as cotton or leather, impeding the smooth economic exchanges on which healthy economies depend. In border areas, the Union greenback currency became the preferred medium for exchange due to its superior stability. Faced with the danger of imminent invasion and the burden of supporting and hosting the military, the border areas tended to be particularly harmed by the war.

The Confederate government passed the Currency Reform Act of 1864 in an effort to stem the rampant inflation ravaging the South. The Act effectively removed one third of all currency in the South from circulation by mandating that all large denomination bills be converted to 4 percent Treasury bonds before April 1, 1864, and imposing a 3-to-2 redemption ratio for small bills after the deadline. As people tried to get rid of their large notes, velocity spiked and in the months prior to the deadline, inflation rose to 23 percent a month. In the summer of 1864, though, price levels in the Confederacy finally stabilized and even declined slightly, just as monetary theory would predict following a contraction in the money supply. However, in the face of continuing pressure to meet war obligations, Congress authorized the printing of an additional $275 million in August of 1864, mostly reversing the effects of the Currency Reform Act.

In contrast with the South, the Union successfully raised the $2.3 billion necessary to fund its war effort without causing hyperinflation. Though inflation was high in the North during the war — prices doubled in most Northern cities — it paled in comparison to the hyperinflation that plagued the Confederacy. The North drastically changed its tax collection system and financial infrastructure to accommodate the burdens of a long, expensive war. These wartime changes ultimately helped reshape the economic face of America.

Whereas the South was mostly unable to raise funds through loans, the North financed roughly 65 percent of its war effort through borrowing. Wealthy Philadelphia financier Jay Cooke successfully orchestrated the sale of huge numbers of war bonds. In order to sell these issues, Cooke launched a massive advertising campaign aimed at middle- and working-class families who traditionally were not seen as a major source of funds. His campaign was a success, with almost 1 million working families purchasing war bonds. This advertising effort presaged the modern era in which bond issues to the general public were used to help pay for wars.

During the war, the Union also managed to expand its tax base and revamp its collection system. After some initial tax measures in 1861, including the first federal income tax in U.S. history, the Union passed the Internal Revenue Act of 1862 which raised the income tax, enacted luxury and consumption taxes, and created the Bureau of Internal Revenue. In contrast to the Confederate bureaucracy where central control was weak and administrative capability lacking, the Bureau of Internal Revenue streamlined federal tax collection, a process so effective that the North raised 20 percent of its wartime revenue through taxation.

The Union Congress also passed several important pieces of financial legislation during the Civil War. In 1861, the financial demands of the war began to deplete the gold reserves of both the banking sector and the Treasury. In response, private banks ceased redeeming currency for gold, and soon the Treasury followed suit. The government passed the Legal Tender Act of 1862, which allowed the issuance of legal tender currency not backed by gold. This marked the first time in U.S. history that a fiat currency, or a currency not backed by some underlying commodity, was used as legal tender. A year later the Union government passed the National Banking Act of 1863 which created a system of nationally chartered and regulated banks to ensure a market for Union war bonds. Preexisting banks were given very strong incentives to become nationally chartered. Once chartered they were subject to federal reserve requirements, had to accept all other national banks’ currencies at face value, and had to hold federal bonds as collateral against note issue.

Both the Legal Tender Act and the National Banking Act were intended to be temporary measures to meet the exigencies of war. However, both sets of reforms lasted long after the conflict ended. More broadly, these acts, coupled with the expansion of taxation and the creation of the Bureau of Internal Revenue, marked an important shift in the power of the U.S. government. After the Civil War, the federal government had much more control over banking regulation and monetary policy, and much more power over the states generally.

Posted by Eddy Elfenbein on June 23rd, 2015 at 10:37 pm

The information in this blog post represents my own opinions and does not contain a recommendation for any particular security or investment. I or my affiliates may hold positions or other interests in securities mentioned in the Blog, please see my Disclaimer page for my full disclaimer.

- Tweets by @EddyElfenbein

-

-

Archives

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- July 2019

- June 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- May 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- July 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- March 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- July 2016

- June 2016

- May 2016

- April 2016

- March 2016

- February 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- July 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- April 2015

- March 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- December 2014

- November 2014

- October 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

- July 2014

- June 2014

- May 2014

- April 2014

- March 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- July 2013

- June 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- August 2012

- July 2012

- June 2012

- May 2012

- April 2012

- March 2012

- February 2012

- January 2012

- December 2011

- November 2011

- October 2011

- September 2011

- August 2011

- July 2011

- June 2011

- May 2011

- April 2011

- March 2011

- February 2011

- January 2011

- December 2010

- November 2010

- October 2010

- September 2010

- August 2010

- July 2010

- June 2010

- May 2010

- April 2010

- March 2010

- February 2010

- January 2010

- December 2009

- November 2009

- October 2009

- September 2009

- August 2009

- July 2009

- June 2009

- May 2009

- April 2009

- March 2009

- February 2009

- January 2009

- December 2008

- November 2008

- October 2008

- September 2008

- August 2008

- July 2008

- June 2008

- May 2008

- April 2008

- March 2008

- February 2008

- January 2008

- December 2007

- November 2007

- October 2007

- September 2007

- August 2007

- July 2007

- June 2007

- May 2007

- April 2007

- March 2007

- February 2007

- January 2007

- December 2006

- November 2006

- October 2006

- September 2006

- August 2006

- July 2006

- June 2006

- May 2006

- April 2006

- March 2006

- February 2006

- January 2006

- December 2005

- November 2005

- October 2005

- September 2005

- August 2005

- July 2005

Eddy Elfenbein is a Washington, DC-based speaker, portfolio manager and editor of the blog Crossing Wall Street. His

Eddy Elfenbein is a Washington, DC-based speaker, portfolio manager and editor of the blog Crossing Wall Street. His