Archive for May, 2009

-

This Just In…

Eddy Elfenbein, May 19th, 2009 at 5:51 pmPeople With Higher IQs Make Wiser Economic Choices, Study Finds

People with higher measures of cognitive ability are more likely to make good choices in several different types of economic decisions, according to a new study with researchers from the University of Minnesota’s Twin Cities and Morris campuses.

The study, set to be published online in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences this week, was conducted with 1,000 trainee truck drivers at Schneider National, Inc., an American motor carrier employing 20,000. The researchers measured the trainees’ cognitive skills and asked them to make choices in several economic experiments, and then followed them on the job.

People with better cognitive skills, in particular higher IQ, were more willing to take calculated risks and to save their money and made more consistent choices. They were also more likely to be cooperative in a strategic situation, and exhibited higher “social awareness” in that they more accurately forecasted others’ behavior.I’m looking forward to authors’ follow-up study, “Your Ass and a Hole in the Ground: A Study on Dissimilarities.”

-

The VIX and Market Returns

Eddy Elfenbein, May 19th, 2009 at 4:17 pmMost commentators assume that low volatility is good for the market. That’s not necessarily the case. All a high low or VIX is at predicting is high or low volatility, not direction.

CNBC reports:Historically, the S&P has seen an average of 3% and 6% gains respectively over the 3 and 6 months that follow a crossover below 30.

That’s a completely useless stat. The general market averages close to those returns anyway. Given the historical sample size, that study simply measures noise and nothing else.

Here are some numbers I came up with:

Since 1990, when the VIX is below 15 (about 31% of the time), the S&P’s annualized return is 7.8%.

When the VIX is between 15 and 20 (27% of the time), the S&P’s annualized return is 2.8%.

When the VIX is between 20 and 25 (22% of the time), the S&P’s annualized return is -1.5%.

When the VIX is over 25 (20% of the time), the S&P’s annualized return is 11.1%.

To the extent there’s a tipping point, it seems to be a VIX of 13. Above 13, the S&P shows an annualized return of 3.0%, below 13 it jumps to 14.1%. However, 13 is a very low VIX reading; it’s been below 13 about 18% of the time.

Outside that, there doesn’t seem to be much of a trend. -

Amazon at $77

Eddy Elfenbein, May 19th, 2009 at 1:17 pmAmazon (AMZN) is at $77 a share!

Really? Is that real money, or Monopoly money or Canadian euros??

If they mean actual U.S. dollars, I wouldn’t pay half that much. -

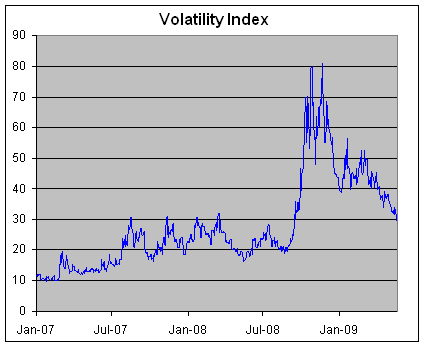

Volatility Chills

Eddy Elfenbein, May 19th, 2009 at 12:10 pmThe Volatility Index (VIX), which is also known as the “fear index,” dipped below 30 today for the first time in eight months. Personally, I’m glad I’m not in my 20s anymore.

At one point, the VIX nearly hit an intra-day high of 90. A lower VIX isn’t necessarily good for the bulls or bears, but it does show that the market is very different from a few months ago. -

Medtronic’s Earnings — Blah

Eddy Elfenbein, May 19th, 2009 at 11:47 amDespite getting some great press for Barron’s, Medtronic’s (MDT) earnings report was rather uninspiring. Their fiscal Q4 earnings came in at $250 million or just 22 cents a share. That’s a huge drop from the 78 cents a share they made a year. However, if you knock out all the charges, and there were many, the company made 82 cents a share which was in line with the Street.

The Wall Street Journal reports:Revenue slipped 0.8% to $3.83 billion. In February, the company had said it expected revenue of about $3.84 billion. Excluding currency fluctuations, revenue grew 5%. Sales of heart-rhythm devices fell 5% as ICD sales declined 3.2%. The spinal business grew 1%.

Cardiovascular revenue was flat amid a 15% fall for stents, the scaffoldings that prop open arteries. The company said late Monday that the Endeavor stent was the first coronary stent to receive the European Economic Area’s CE mark of approval for treating patients with acute coronary syndrome, which includes unstable angina and heart attacks.What’s more, the company is cutting 1,500 to 1,800 jobs. For this fiscal year, Medtronic projects earnings at $3.10 to $3.20 per share where the Street was looking for $3.20.

I have to agree that the stock is cheap, but I think it will become even cheaper. If you’re looking to add shares, wait for it to drop below $30.

Here’s a look at MDT’s sales and earnings for the past several quarters:

Quarter………..EPS………….Sales

Jul-01…………$0.28………..$1,455.70

Oct-01………..$0.29………..$1,571.00

Jan-02………..$0.30………..$1,592.00

Apr-02………..$0.34………..$1,792.00

Jul-02…………$0.32………..$1,713.90

Oct-02………..$0.34………..$1,891.00

Jan-03………..$0.35………..$1,912.50

Apr-03………..$0.40………..$2,148.00

Jul-03…………$0.37………..$2,064.20

Oct-03………..$0.39………..$2,163.80

Jan-04………..$0.40………..$2,193.80

Apr-04………..$0.48………..$2,665.40

Jul-04…………$0.43………..$2,346.10

Oct-04………..$0.44………..$2,399.80

Jan-05………..$0.46………..$2,530.70

Apr-05………..$0.53………..$2,778.00

Jul-05…………$0.50………..$2,690.40

Oct-05………..$0.54………..$2,765.40

Jan-06………..$0.55………..$2,769.50

Apr-06………..$0.62………..$3,066.70

Jul-06…………$0.55………..$2,897.00

Oct-06………..$0.59………..$3,075.00

Jan-07………..$0.61………..$3,048.00

Apr-07………..$0.66………..$3,280.00

Jul-07…………$0.62………..$3.127.00

Oct-07………..$0.58………..$3,124.00

Jan-08………..$0.63………..$3,405.00

Apr-08………..$0.78………..$3,860.00

Jul-08…………$0.72………..$3.706.00

Oct-08………..$0.67………..$3,570.00

Jan-09………..$0.71………..$3,494.00

Apr-09………..$0.78………..$3,830.00 -

The ungovernable state

Eddy Elfenbein, May 18th, 2009 at 10:37 pmThere’s an election tomorrow in California. If several initiatives pass, the state budget deficit will be $15.4 billion. If they fail, it will be $21.3 billion.

The state is royally screwed. It’s not economics, it’s the state’s political culture.

Between democracy, immigration and big government, you can choose any two. You can’t have all three.

The Economist reports:The broken budget mechanism and the twin failures in California’s representative and direct democracy are enough to guarantee dysfunction. The sheer complexity of the state exacerbates it. Peter Schrag, the author of “California: America’s High-Stakes Experiment”, has counted about 7,000 overlapping jurisdictions, from counties and cities to school and water districts, fire and park commissions, utility and mosquito-abatement boards, many with their own elected officials. The surprise is that anything works at all.

As a result, there is now a consensus among the political elite that California’s governance is “fundamentally broken” and that the state is “ungovernable, unless we make tough choices”, as Antonio Villaraigosa, the mayor of Los Angeles and a likely candidate for governor next year, puts it.Notice that what needs to be done is perfectly clear. We all know the answer. Like any tragedy, the problem is simply a lack of will.

-

My Lunch with Timmy

Eddy Elfenbein, May 18th, 2009 at 4:35 pmI went to see Treasury Secretary Tim Geithner be interviewed by Newsweek editor Jon Meacham today at the National Press Club. The back story is that after 76 years, Newsweek is relaunching itself. The new issue is out today and the magazine is smaller and more “engaged,” though it’s also more expensive. Today’s interview was part of their rebranding campaign.

The folks at Clusterstock were invited and they generously passed their invitation onto me. This was an odd day to see the Treasury secretary be interviewed since the Washington Post ran a story this morning on the sad state of affairs at the department. The article’s message was clear: Geithner is a weak manager and the White House has the whole department on a tight leash.Government officials, inside the Treasury and out, say the unresolved issues are piling up in part because of vacancies in the department’s top ranks. But some of the officials also cite the Treasury’s ad-hoc management, which is dominated by a small band of Geithner’s counselors who coordinate rescue initiatives but lack formal authority to make decisions. Heavy involvement by the White House in Treasury affairs has further muddied the picture of who is responsible for key issues, the officials add.

To his credit, Meacham led off by mentioning the article and asked Geithner about it. This turns to problem I have with Geithner—he seems to have the soul of a bureaucrat. He speaks too quickly and he avoids the heart of nearly every question.

This is, of course, what people in power are paid to do. But when someone as artful as Obama does it, you feel that the question has been answered. With Geithner, you simply feel like he’s evading you and he has contempt for the question. On top of that, he seems so damn ineffectual. Once you see the package at work, it doesn’t inspire much confidence. Especially when you compare him with his boss, the gap is downright embarrassing.

So what was his answer? He garbled on about more time, things were progressing nicely, yadda yadda yadda and the administration was “ahead of the curve.” You just knew that phrase was coming. Still, he never addressed the issue at hand which is him—and ironically, that answers the question.

When asked about the economy, Geithner said that things were stabilizing but there’s still a lot of pain out there. (Gee, thanks for that, Tim.) When asked about the efficacy of the Fed, he said that it’s performed “very well over time,” but didn’t comment more about the current Fed. Bernanke’s term as Fed Chair expires next year.

The closest Geithner came to being emphatic was we he reiterated the administration’s view that something had to be done quickly and be done big, so the issue of the debt and deficit weren’t top priorities. I would have like to see Meacham press him further about how the stimulus us being spent, but no such luck.

Meacham asked Geithner how much money he makes as Treasury secretary. Geither said that he’s generously compensated and that he makes under $200,000. Ugh. Here’s a question that can be answered with a specific number and its public information, yet even here, Geithner still bobs. Fortunately, he went on to say that he doesn’t favor compensation caps for bankers. Instead, he supports altering scope of incentives, but still he was vague on that point outside of the usual boiler plate like “say on pay.”

Meacham threw a bit of a curveball by mentioning critics to the left of the administration, specifically Paul Krugman, and the charge that they’re too soft on bankers. Geithner completely dodged the whole thing.

Perhaps the most illuminating part was when Meacham turned to the issue of California and states in general. Geithner said they’re in close consultation with the states. When Meacham pressed him about a federal bailout, Geithner said that he wouldn’t use the words “federal” or “bailout,” and repeated that he was in close consultation with the states. I’m not sure what to take from that.

Meacham concluded by asking Geithner about being named one of “Barack’s Beauties” by People. At this point the Treasury Secretary simply blushed. Meacham made some joke about Alexander Hamilton probably never blushed, and Geithner being in “close consultation” with People.

All in all, I would rather have seen Geithner (or anyone) interview Meacham. In addition to being a thoughtful observer of religion in America, he recently won the Pultizer Prize for American Lion, his book on Andrew Jackson. Plus, he’s in the middle of trying to revamp one of the country’s oldest and most influential news magazines. -

Geithner at the National Press Club

Eddy Elfenbein, May 18th, 2009 at 10:33 amI’m heading off to the National Press Club to hear Tim Geithner be interviewed by Newsweek’s Jon Meacham.

This is rather a delicate time for the Treasury Secretary. The Washington Post ran an article this morning saying there’s no coherence at the Treasury Department. The claims are that he’s a weak manager, important slots are still unfilled, important decisions are made on an ad hoc basis and the White House grants it little autonomy.

The article states that the White House even reviewed the department’s design for its web site (btw, the right side bar needs a wider margin).

I’ll have a complete report when I get back. -

The Strange Death of American Capitalism

Eddy Elfenbein, May 17th, 2009 at 2:54 pmBook Review of Bailout Nation by Barry Ritholtz

In The Strange Death of Liberal England, George Dangerfield famously described how the British Liberal Party—and by extension, England’s once-unshakable faith in liberalism—suddenly and unexpectedly vanished. Despite its outward appearance of solidity, once liberalism was challenged, it crumbled to dust. How could a faith that was so dominant for so long, suddenly disappear; not only die quickly—indeed with a whimper—but do so without putting up any resistance?

These are similar questions future historians will have when they look back at the first decade of twenty-first century America. At the dawn of the new millennium, America’s faith in capitalism was also unshakable. Yet, within a few short weeks in 2008, the entire edifice came crashing down. Even voting didn’t seem to matter. First under a Republican administration and then under a Democratic one, large sectors of the economy received unprecedented amounts of government support. A staggering $15 trillion of taxpayer money has been put on the line.

The American economy reached its humiliating nadir at Davos earlier this year when our fiscal profligacy was criticized by the Wen Jiabao, the premier of what was once-called Red China. Worst of all, he was right.

What Happened?

In Bailout Nation: How Greed and Easy Money Corrupted Wall Street and Shook the World Economy, Barry Ritholtz takes on that question with gusto and the result is a wonderfully engaging book. Bailout Nation describes not only what happened and what went wrong, but also why. Don’t worry, you don’t need an advanced degree in economics to follow the story. Bailout Nation manages to be both comprehensive and easy to read.

Ritholtz is already known to countless investors through his invaluable blog, The Big Picture. (Full disclose: He’s been a supporter of CWS from its earliest days.) I have to confess to having some initial reservations about Ritholtz’s book. What makes him a great blogger, I feared, might not transfer well to a 300-page sustained argument. Let’s just say that Ritholtz isn’t exactly a “shades of gray” kind of guy. When a rapier is needed, Ritholtz is fully willing to use a cluster bomb. If you don’t think it’s possible to get a true sense of moral outrage over, say, the latest BLS report, well…you haven’t read The Big Picture.

Fortunately, my fears were unfounded. Ritholtz does very well in book form. His editor, Aaron Task, served him well; the prose is compact and well-organized, though I’m fairly certain of the sentences where Ritholtz shook off all editorial changes. Where Ritholtz truly shines is in drawing connections between seemingly disparate events; the fall of Bear Stearns, oleaginous mortgage brokers, the repeal of Glass-Steagall, the growth of credit default swaps, even the effects of reforming the Consumer Price Index, all play a role in this complex mess of unintended consequences, vicious cycles, ideological blindness and abject stupidity. I can’t remember the last time I had so much fun reading about the Apocalypse.

There are, however, a few minor errors. The Jefferson quote, “Banking establishments are more dangerous than standing armies” (page 15) is probably bogus. Also, on page 96, Ritholtz writes, “the psychological impact that feeling financially flush has on spending cannot be underestimated.” He surely means overestimated. These errors are minor of course, and it may be a reflection of covering events in real time.

Even before its release, Bailout Nation itself became a news story. In February, McGraw-Hill, the originally publisher, announced that it was ditching the project. Ritholtz claimed it was due to his criticisms of the Wall Street ratings agencies (McGraw-Hill owns Standard & Poor’s). McGraw-Hill denied this although curiously, the editor Ritholtz had been working with, resigned one week later. Fortunately, John Willey & Sons picked up the project and brought it to life (or, if you prefer, bailed it out).

Lockheed Was the Original Sin

So how did we end up were we are? Ritholtz persuasively makes the case that we didn’t suddenly abandon our capitalist faith. Instead, he argues that our fondness for bailouts isn’t new. Ritholtz pinpoints our original sin in the 1971 bailout of Lockheed. By today’s standard, that bailout was laughably small—just $250 million.

The important point is that a new standard had been established, and the government and Corporate America responded accordingly. Soon, bailouts became like a narcotic. Our fixes could only be satiated by steadily larger rescues. Soon Penn Central received a bailout, followed by Chrysler a few years later, then Continental Illinois (which ironically found itself in the hands of Bank of America).

Ritholtz agues that the bailouts, even when successful in the short-term, do considerable long-term damage. After the Chrysler bailout, for example, the already somnolent auto industry grew even more complacent. Ritholtz considers an alternative history: What if Chrysler had been allowed to fail? Might Detroit have reformed itself? We’ll never know because as the public became slowly inured to these bailouts, they were free to grow larger.

Ritholtz expands his argument by adding the machinations of the Federal Reserve to the growing bailout trend. This is a crucial point because too few observers see the motives behind the central bank. Any good story needs a top-notch villain and in Bailout Nation, it’s a certain Randian jazz musician named Alan Greenspan.

The Mess That Greenspan Made

Ritholtz doesn’t suffer fools gladly and Greenspan gets a well-deserved skewering. Ritholtz tracks how Greenspan purposely and quite clearly altered the Fed’s mandate to include supporting asset prices. The facts Ritholtz presents are strong. The Fed-orchestrated bailout of LTCM had a profound effect on Wall Street’s risk-taking mentality. Whenever the market tumbled, Greenspan jumped in to cut rates. Bubbles, however, in tech stocks and later in housing were allowed to grow unchecked.

According to Ritholtz, it was Dr. Greenpan’s tonic of absurdly low interest rates that led to an historic housing bubble and all the unpleasantness that followed. The effect was far more damaging than easy money.

Ritholtz stresses that the Fed’s policies changed the rules of the game. For example, the bond market was now forced into a reckless “scramble for yields.” This in turn fed the practice of securitization which, in turned, fueled the disgraceful behavior of the ratings agencies. When yields were low, mischievous behavior flourished. At each juncture, the dots connect back to Greenspan who even disregarded his fellow members of the Federal Open Market Committee.

Incidentally, the section on ratings agencies (pages 111 to 113) is hardly controversial. Ritholtz simply states what’s widely known, that the ratings practiced a form of payola. There’s no other way to say it—the agencies abandoned their professional and moral obligations.

Real Capitalists Nationalize

As for the debt crisis, Ritholtz writes, “From 1 million B.C. up until the present day, the ability to repay the debt has always been the dominant factor—except, however, for a brief five-year period starting around 2002.” It’s sadly true. One strawberry picker in California got a $720,000 loan despite his annual income of $14,000. The system morphed into capitalism without capital.

Technically, the bubble wasn’t in housing, it was in credit. The numbers are staggering. At one point, close to half of all the new jobs created were tied to real estate. Between 2003 and 2006, 75% of GDP growth was solely due to mortgage equity withdrawals. From December 2006 to December 2007, the notional amounts outstanding of credit fault swaps more than quadrupled from $14 trillion to $58 trillion.

Bailout Nation is quick-paced and Ritholtz sprinkles the test with illuminating charts and eye-catching statistics (i.e., Bear Stearns’ liquidity pool dropped by 90% in three days). He wryly notes that it you want to play the bailout game, make sure you do it first and do it big. Ritholtz also has a novel theory for the explosion in executive compensation on Wall Street, but I won’t spoil it for you here.

Characteristicly, Ritholtz isn’t shy about naming names. In Chapter 19, he lists the folks most at fault for the credit mess. It won’t surprise you that Greenspan tops the list. Personally, I think the “savings glut” deserves more attention. Chapter 20 is an interesting take-down of the phony causes of our troubles, like naked shorting and the Community Reinvestment Act.

I should add that Ritholtz is an equal opportunity critic. Many liberals won’t be pleased by his criticisms of bailouts and his dismal of systemic risk (or more accurately, the threat of systemic risk). Parts of the book could have been written by Milton Friedman. Ritholtz even repeats Friedman’s famous mantra, “there is no free lunch.” Plus, any book with a chapter titled, “The Virtues of Foreclosure,” isn’t about to win a Bleeding Heart of the Year award.

Conservative will certainly take issue with Ritholtz’s criticisms of financial deregulation and his call for therapeutic nationalization. What I find most disturbing is how much of the government’s behavior was simply arbitrary. Ritholtz makes it clear: They were just making it up as they went along.

Ritholtz favors temporarily nationalizing insolvent banks. Mind you, this ain’t exactly Pol Pot. Ritholtz merely wants bad banks taken out, cleaned up and restored to health. He believes it’s the solution that will cause the least damage (“real capitalists nationalize”). I think he’s on sound footing here. It’s odd that we can watch Citigroup fall from $57 to 97 cents, yet bringing it that last bit to $0 is somehow unacceptable. Ritholtz concludes, “Real capitalists nationalize; faux capitalists look for the free lunch.”

At the beginning of The Strange Death of Liberal England, Dangerfield wrote of the Liberal’s final triumph, “From that victory they never recovered.” Let’s hope American capitalism doesn’t share their fate.

-

Barron’s Calls Shares of Medtronic “Cheap”

Eddy Elfenbein, May 16th, 2009 at 8:12 pmIn this weekend’s Barron’s, Neil Martin makes the case for Medtronic (MDT):

Good news or bad, Medtronic’s stock is cheap. The shares are trading for 11.4 times fiscal ’09 estimates, and 10.5 times fiscal ’10 projections of $3.20 a share. That’s well below the 13 price/earnings multiple on the Standard & Poor’s 500 Health Care Equipment and Services index, and a P/E of 15 on the broader S&P. Medtronic itself hasn’t had such a low P/E in at least 10 years.

Analyst Rick Wise at Leerink Swann rates the stock Market Perform, but hails the ability of management, led by Chief Executive Officer William Hawkins, to set “achievable growth targets” resulting in 5% to 7% organic top-line growth. “Longer term, for investors who have the patience to watch this scenario unfold, Medtronic is one of the least expensive stocks in the health-care universe,” he says.

Earnings are coming out on Tuesday.

-

-

Archives

- May 2025

- April 2025

- March 2025

- February 2025

- January 2025

- December 2024

- November 2024

- October 2024

- September 2024

- August 2024

- July 2024

- June 2024

- May 2024

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- July 2019

- June 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- May 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- July 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- March 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- July 2016

- June 2016

- May 2016

- April 2016

- March 2016

- February 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- July 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- April 2015

- March 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- December 2014

- November 2014

- October 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

- July 2014

- June 2014

- May 2014

- April 2014

- March 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- July 2013

- June 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- August 2012

- July 2012

- June 2012

- May 2012

- April 2012

- March 2012

- February 2012

- January 2012

- December 2011

- November 2011

- October 2011

- September 2011

- August 2011

- July 2011

- June 2011

- May 2011

- April 2011

- March 2011

- February 2011

- January 2011

- December 2010

- November 2010

- October 2010

- September 2010

- August 2010

- July 2010

- June 2010

- May 2010

- April 2010

- March 2010

- February 2010

- January 2010

- December 2009

- November 2009

- October 2009

- September 2009

- August 2009

- July 2009

- June 2009

- May 2009

- April 2009

- March 2009

- February 2009

- January 2009

- December 2008

- November 2008

- October 2008

- September 2008

- August 2008

- July 2008

- June 2008

- May 2008

- April 2008

- March 2008

- February 2008

- January 2008

- December 2007

- November 2007

- October 2007

- September 2007

- August 2007

- July 2007

- June 2007

- May 2007

- April 2007

- March 2007

- February 2007

- January 2007

- December 2006

- November 2006

- October 2006

- September 2006

- August 2006

- July 2006

- June 2006

- May 2006

- April 2006

- March 2006

- February 2006

- January 2006

- December 2005

- November 2005

- October 2005

- September 2005

- August 2005

- July 2005

Eddy Elfenbein is a Washington, DC-based speaker, portfolio manager and editor of the blog Crossing Wall Street. His

Eddy Elfenbein is a Washington, DC-based speaker, portfolio manager and editor of the blog Crossing Wall Street. His