Archive for February, 2014

-

Yellen’s Testimony

Eddy Elfenbein, February 11th, 2014 at 10:36 amTwice a year, the Chairman of the Federal Reserve heads up to Capitol Hill to take questions from Congress. This is part of the Humphrey Hawkins law. Each session is a two-day affair, one in front of each finance committee. Today is new Fed Chair Janet Yellen’s first Humphrey Hawkins testimony.

This is an interesting time for the Fed as they’ve started tapering but the last two job reports were rather mushy. While the Fed has consistently said they’re not on a pre-set course, they don’t appear to be wavering. At least, not yet.

Here are the key parts from Yellen’s testimony:

Our current program of asset purchases began in September 2012 amid signs that the recovery was weakening and progress in the labor market had slowed. The Committee said that it would continue the program until there was a substantial improvement in the outlook for the labor market in a context of price stability. In mid-2013, the Committee indicated that if progress toward its objectives continued as expected, a moderation in the monthly pace of purchases would likely become appropriate later in the year. In December, the Committee judged that the cumulative progress toward maximum employment and the improvement in the outlook for labor market conditions warranted a modest reduction in the pace of purchases, from $45 billion to $40 billion per month of longer-term Treasury securities and from $40 billion to $35 billion per month of agency mortgage-backed securities. At its January meeting, the Committee decided to make additional reductions of the same magnitude. If incoming information broadly supports the Committee’s expectation of ongoing improvement in labor market conditions and inflation moving back toward its longer-run objective, the Committee will likely reduce the pace of asset purchases in further measured steps at future meetings. That said, purchases are not on a preset course, and the Committee’s decisions about their pace will remain contingent on its outlook for the labor market and inflation as well as its assessment of the likely efficacy and costs of such purchases.

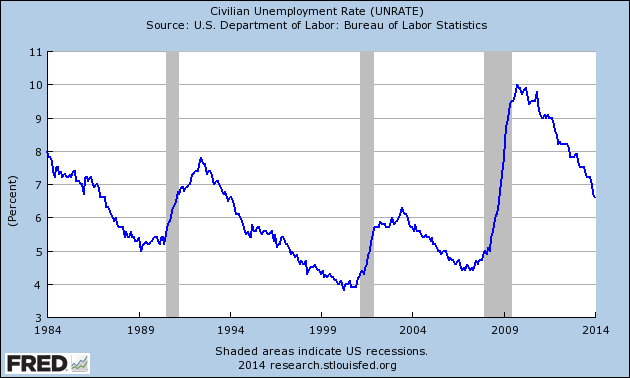

The Committee has emphasized that a highly accommodative policy will remain appropriate for a considerable time after asset purchases end. In addition, the Committee has said since December 2012 that it expects the current low target range for the federal funds rate to be appropriate at least as long as the unemployment rate remains above 6-1/2 percent, inflation is projected to be no more than a half percentage point above our 2 percent longer-run goal, and longer-term inflation expectations remain well anchored. Crossing one of these thresholds will not automatically prompt an increase in the federal funds rate, but will instead indicate only that it had become appropriate for the Committee to consider whether the broader economic outlook would justify such an increase. In December of last year and again this January, the Committee said that its current expectation–based on its assessment of a broad range of measures of labor market conditions, indicators of inflation pressures and inflation expectations, and readings on financial developments–is that it likely will be appropriate to maintain the current target range for the federal funds rate well past the time that the unemployment rate declines below 6-1/2 percent, especially if projected inflation continues to run below the 2 percent goal. I am committed to achieving both parts of our dual mandate: helping the economy return to full employment and returning inflation to 2 percent while ensuring that it does not run persistently above or below that level.

-

The Single-Best Metric: EV/EBITDA

Eddy Elfenbein, February 11th, 2014 at 9:50 amHere’s a post for new investors—and perhaps a refresher for more experienced ones.

I often tell readers not to rely on one metric or ratio. There’s simply no magic formula for stock success. Instead, investors should consult a broad spectrum of numbers to get a clear view of a company’s worth. Having said that, one of the best ratios out there is EV/EBITDA. In fact, some academic research has shown that it’s the single-best valuation measure there is.

So what do all these letters mean? I’ll break it down for you in plain English. EV/EBITDA stands for Enterprise Value divided by Earnings Before Interest, Taxes, Depreciation and Amortization.

Let’s start with the numerator, Enterprise Value (sometimes called total enterprise value), which is basically a fancier version of a company’s market value.

To calculate EV, you start with a company’s market value (the number of shares times the market price). You then add the amount of debt they hold, both short-term and long-term, and at current market value. Then you subtract the amount of cash they have.

This makes sense, because if you’re going to buy out a company, you’re acquiring their debt too, and you can pocket the cash.

Those are the most important differences between EV and market cap, but Enterprise Value also includes things like minority ownership in other companies. There are lots of public companies that own small stakes in other public companies. These may be spin-offs in which they’ve held onto some shares. Perhaps they were considering a merger. The problem is that when an asset you own soars in price, it inflates your equity and therefore tends to lower your ROE, even though you didn’t do anything.

Now let’s turn to the denominator, EBITDA, which stands for Earnings Before Interest, Taxes, Depreciation and Amortization. When we look at a business, we want to know about the dollars coming in compared with the dollars going out. Ideally, we want to isolate the numbers that are closest to showing us the firm’s pure business efficiency. In that regard, EBITDA is beneficial because it tries to be neutral about the company’s capital structure (that’s why we don’t include interest).

Think of it as taking all the revenue and subtracting the costs that solely go into running the business. It’s the business end of the business separated from the financing end of the business. When you look at net income, you’re also factoring in what the CFO has been up to, and of course, Uncle Sam’s cut. While those are important, these variables are a step removed from business operations. The downside of EBITDA is that it can be abused by companies declaring as “one-off” costs things that should really be considered normal costs.

Let me add another important generalization. Strong companies aren’t normally done in by too much debt. It’s certainly possible, and has happened many times. But the more common path is that weak companies acquire too much debt because they’re weak, in an attempt to cure their weakness.

You can find the EV/EBITDA for a stock on Yahoo Finance. Click on the Key Stats page, and it’s the ninth one down. As a rule of thumb, any EV/EBITDA below 10 is the sign of a good value.

-

Morning News: February 11, 2014

Eddy Elfenbein, February 11th, 2014 at 6:35 amSpot Gold Hits 3-Month High With Eyes on Yellen

Five Ways China’s Slowdown Will Ripple Across Globe

Blankfein Says Emerging Markets in Better State Than in ’98

Justice Department Sued Over $13 Billion JPMorgan Pact

Revelations by AOL Boss Raise Fears Over Privacy

Icahn Retreats From Apple Battle on Stock Buybacks

Casino Owners Battle Over Online Gambling

Branson Escalates War of Words With Qantas

L’Oreal to Buy Part of Nestle Stake After 40 Years of Ownership

McDonald’s US Sales Chilled by January Weather

Facebook’s Mark Zuckerberg is 2013’s Top Philanthropist. Youngest, Too.

Mary Barra’s GM Pay Could Top $14 Million, Putting Her in the Big Three

Where Alpha Chasers Dare to Venture

Epicurean Dealmaker: Gedankenexperiment

Joshua Brown: 41% of the S&P 500 Beating on Earnings and Revenue

Be sure to follow me on Twitter.

-

So Then This Happened

Eddy Elfenbein, February 10th, 2014 at 6:04 pmCNBC, First in Business Worldwide

-

The Market’s Two Speeds

Eddy Elfenbein, February 10th, 2014 at 9:18 am“How did you go bankrupt?” “Two ways. Gradually, then suddenly.”

― Ernest Hemingway, The Sun Also RisesOne of the important truths about investing is that the stock market tends to move at two speeds. Bull markets are long, slow, upwards crawls, while bear markets are sudden, precipitous and painful. These, of course, are generalizations, but they’re sufficiently accurate to merit further discussion.

The reason for this dichotomy is, in my opinion, the market’s fixation on disaster. You can create a small market with 1,000 happy, well-balanced investors; yet when they come together, the collective whole will be a sputtering, neurotic mess. That’s just how markets are. They always hold the suspicion, to a greater or lesser degree, that everything’s a fraud and utter ruin is just around the corner.

I can show this to you in concrete terms. Recently I looked at the S&P 500’s daily performance since 1957. I divided all the days into two groups: those with daily changes greater than 1.25%, and those with changes of less than 1.25%. The direction of the change, up or down, didn’t matter. I only looked at daily volatility.

The results were eye-opening. In terms of market performance, low volatility demolished high volatility. It wasn’t even close. The low-vol group, taken together, accounted for the market’s entire gain spread over 56 years. But the high-volatility days, coming an average of once every seven days, were net losers. Annualized, low volatility returned an average of 8.9% per year, while the high-volatility group lost 5.9% per year.

In simple terms, scared markets are bad markets.

Market gurus enjoy discussing tail risk and the importance of fat tails, but they neglect the other part—the tall peaks. Yet we can see that it’s in these numerous small changes that the difference is truly made.

Investors need to understand that freak-outs happen. They just do. They’re painful because they temporarily confirm and amplify the market’s worst fears.

Fortunately for us, these periodic panics are what give us the value premium. After all, you’re more likely to jump ship from the leakiest vessel. This is why the value premium shows up again and again and again. It’s not some transient anomaly, but rather the direct result of human nature.

-

Sir John Templeton: The Last Yankee

Eddy Elfenbein, February 10th, 2014 at 7:47 amThe disappearance of the WASP ruling class that once presided over American business has gone unlamented by almost everyone—including the WASPs themselves, whose moral confidence suffered a fatal wound during the Vietnam era and never recovered. Yet every so often, we’re reminded by certain figures of just how impressive the Protestant ethos at its best could be, and how much we’ve lost with its passing.

Sir John Templeton is one such figure. Templeton wasn’t a WASP: born and bred in rural Tennessee, he was too plebian ever to fit in with the yachting set at Bar Harbor, and too intellectually superior to want to do so in the first place. Nevertheless his life, which spanned the American century, embodied seemingly every one of the cardinal Yankee virtues—discipline, thrift, service to others, disdain for material display, always doing the right thing, even at cost to oneself—without any of the Anglophile trappings or snobbishness. All the more symbolic, then, was his demise on July 8, 2008, just two months before the markets plunged into turmoil. When he died, it was as though a whole era in American finance died along with him.

Templeton was born in 1912 in Winchester, Tennessee, a small hamlet later revitalized by the Tennessee Valley Authority. He seems to have inherited the distinctively Protestant conflation of moral probity and the profit motive from his father, a small-time entrepreneur and lawyer who ran a cotton-gin business after World War I. Harvey Templeton would buy up plots of land around Winchester, and if the tenant farmers living on them were hard up, he’d let them continue on free of charge. His ethically minded son appears to have taken due note of the charitable imperative.

It was hard not to, in those days. Especially in Tennessee, where a single bad harvest was often all that separated keeping afloat from going under. As it turned out, the Templetons themselves soon felt the sting of necessity: when the Depression hit, young John received a letter saying his father would no longer be able to finance his stint at Yale, then in its second semester. Undaunted, the future billionaire turned to poker to pay his tuition.

After graduation, Templeton decided he wanted to step outside the confines of the usual and see the world. So he booked deck passage on a series of steamers and wandered around Europe and the Middle East, sleeping out of doors and eating dry bread to save money—and occasionally hitting up the casinos to replenish his funds. His mother at one point gave her son up for dead. The 24-year-old was, however, very much alive, and the international outlook sown during his peregrinations would later bear rich fruit.

For in those days, globalization as a concept didn’t exist. Much of the world was still carved up into empires, usually under European control, rendering the notion of emerging markets a moot point. But Templeton saw opportunities everywhere he went. Many years later, that change of vision would be the key to his empire.

First, however, he had to amass some capital. So after marrying Judith Folk, an unconventional Nashville belle and Wellesley grad, and furnishing a sixth-story walkup in Manhattan with cast-off furniture picked up on street corners, he set about becoming an investor. From the start, he distinguished himself with his against-the-grain way of doing things. In September 1939, with the markets in free fall from the impending war, he borrowed $10,000 to buy up 100 shares of every stock worth $1 or less on the New York Stock Exchange. Of the 104 companies purchased, 100 turned a profit, sometimes sizeable, when industry picked up again after 1945. His motto, he said, was to wait till the moment of “maximum pessimism,” and then pounce.

Still, times were lean before those rewards started to roll in. When Templeton bought an investment company in 1944, he had only five families as clients and didn’t see a dime’s worth of profit for three years. Eventually, though, his buy-and-hold approach began to pay off, to the point where the family could at last take a vacation, to Nassau in the Bahamas. There, tragically, Judith was killed in a freak motor-scooter accident. She was just 39.

Judith’s death was, according to the family, a loss from which Templeton never fully recovered. He did remarry, however, seven years later, this time to Irene Reynolds Butler. During this time, too, his business underwent a profound transition, with the launching in 1954 of the Templeton Growth Fund, a pioneer in the now-ubiquitous field of globally diversified mutual funds. With seed capital of some $13 million dollars and offices in an attic above a police station in the Bahamas, it was among the first firms to invest in Japan and Korea, which in those days fell under the heading of emerging markets. To manage the fund, Templeton hired John Galbraith, a gifted analyst whose trust in his boss was so implicit that he worked for him until his retirement in the 1990s without ever signing a written contract.

It wasn’t long before Templeton Growth really started to pay dividends. Galbraith’s skillful management and Templeton’s own vision made their funds top performers: $10,000 invested with them in 1954 would have grown to $2 million in 1992, when Templeton sold his stake to the Franklin Group—an annualized average return of 14.5%. Money magazine called Templeton “arguably the greatest global stock picker of the century.”

As Templeton’s fortune grew, so did his philanthropy. A longtime elder of his Presbyterian church, he believed in a non-dogmatic, open-ended Christianity that allowed for dialogue with both science and other faiths. Such eschewals of doctrine were (and remain) common in much mainline Protestantism, and ultimately led him to set up the Templeton Foundation, a kind of spiritual think tank that gave grants to scholars interested in exploring the sacred implications of secular disciplines ranging from psychology to physics. He deliberately set the cash value of its top award, the Templeton Prize, at $1 million as an implicit critique of the Nobel, which ignored “life’s spiritual dimension.” Templeton would ultimately give away some $1 billion to charity, and even renounced his American citizenship to funnel the $100 million in taxes that he would otherwise have paid upon the sale of Templeton Growth towards more charitable ends. In 1987, Queen Elizabeth knighted him for his philanthropic efforts; twenty years later, Time named him as one of its 100 Most Influential People for the same reason.

Templeton maintained his spiritual serenity and curiosity well into old age, but he also voiced increasing skepticism regarding the barbarization of America’s economy. He pulled out of the dotcom and Nasdaq tech-stocks market in early 2000, just before the crash, and in 2003 predicted the collapse of the housing sector, which he saw as fueled by irrationalism and greed. More trenchantly, he wrote a private memorandum in 2005 predicting that the world would soon be plunged into financial chaos, and later publicly pronounced the stock market “broken.” For the man who all his life never flew first class and who made his own notebooks from scrap computer paper, dismay and consternation were the only possible reaction at finding the Depression-era values on which he’d been raised jettisoned in favor of the new Wall Street’s crassness and institutionalized grift. As though to signal the starkness of the change in the America he renounced, the truth of Templeton’s gloomy prophecies was already apparent when he died in late 2008.

The days of investors like John Templeton are done. The values he embodied are fast being replaced by, or transformed into, the self-seeking and self-promoting of the new careerist meritocracy. In the future, his life will serve as a reminder of another, older America, where money wasn’t everything and character was ultimately an individual’s greatest asset.

(Speaking of self-promoting, you can sign up for my free investing newsletter here.)

-

Morning News: February 10, 2014

Eddy Elfenbein, February 10th, 2014 at 6:27 amEU Banks’ Risk-Free Debt Addiction Threatens ECB-Led Overhaul

Japan Current Account Surplus Smallest on Record

Turkish Industrial Production Rose in December

Eyes On Federal Reserve’s Janet Yellen After Poor Jobs Print For Dollar

Yellen’s Fed: A Champion of Main Street

European Shares Nudge HIgher as Nokia Gains on HTC Settlement

Deutsche Telekom to Pay $1.1 Billion in Czech Unit Buyout

Boeing Sees Asia-Pacific Fleet Nearly Tripling Over Next 20 Years

Toyota to End Australia Production

Nissan Becomes Least Profitable Japan Carmaker Amid Yen Boon

Icahn’s Proposal for $50 Billion Apple Buyback Opposed by ISS

Barclays 2013 Profit Declines 26%, Missing Analyst Estimates

AOL’s Armstrong Apologizes After 401(k) Gaffe Stirs Controversy

Jeff Miller: Weighing the Week Ahead: Will Yellen Signal a Policy Change?

Be sure to follow me on Twitter.

-

JFK: “Life Is Un-Feah”

Eddy Elfenbein, February 7th, 2014 at 4:44 pm -

January NFP +113,000

Eddy Elfenbein, February 7th, 2014 at 10:32 amAnother tepid jobs report. The economy created 113,000 net new jobs last month, well below the estimate of 181,000. The unemployment rate falls to 6.6%. One good spot is that the labor force participation rate ticked up to 63.0% from 62.8% in December.

Private employers added 142,000 positions to their payrolls in January, while government at all levels shed 29,000. Among individual sectors, manufacturing had a gain of 21,000 jobs, while employment in construction jumped by 48,000.

The employment-population ratio, which has been falling as more workers drop out of the job market, edged up 0.2 percentage points to 58.8 percent. In recent years, the exit of people from the work force has reduced the unemployment rate, but it is a sign that people are giving up hope of finding a job amid slack conditions, hardly the way policy makers would like to see joblessness come down.

Despite Friday’s report, another steady reduction in bond purchases is likely when Fed policy makers next meet in March. A disappointing showing in February’s report, however, might change that.

Wintry conditions that held back hiring were blamed for the weakness in December, a theory popular among more optimistic economists after those numbers came out in early January.

-

CWS Market Review – February 7, 2014

Eddy Elfenbein, February 7th, 2014 at 6:44 am“The first principle is that you must not fool yourself, and

you are the easiest person to fool.” – Richard FeynmanThe tumult that we saw last week continued into this week. Thanks to a soggy ISM report, the S&P 500 had its worst day on Monday in more than seven months. The index plunged to its lowest level since mid-October.

But the bears don’t have the upper hand just yet. I’m not a proponent of technical analysis, but I do keep an eye on the S&P 500’s 200-day moving average (that’s simply the average of the previous 200 trading days). We’re still above it, and that’s good news for bulls.

The ISM Index for January dropped to 51.3 from 56.5 for December, which is a big move for just one month. The ISM is a survey, and a number of respondents said they had been affected by adverse weather. Bad weather in the winter shouldn’t be a surprise, but it will be interesting to see if there’s a sharp rebound when the next report comes out.

A positive report on jobless claims on Thursday helped the market rebound, and we had our best day of 2014. There had been a slight bump up in jobless claims recently, so Thursday’s report was welcome news. The number of Americans filing first-time jobless claims fell by 20,000 to 331,000. That was better than what economists had been expecting.

I’m writing this to you ahead of Friday’s big jobs report, and that’s been on Wall Street’s mind all week. Here’s where we stand: Since the Fed has already started tapering its bond purchases, these jobs reports aren’t quite as important as they used to be. But the December report was weak, so that could change the narrative that the jobs market is “gradually improving.” Was December just weak due to weather, or could this mean the economy has downshifted?

I suspect, though I’m not certain, that the recent weakness was due to lousy weather around the country. Normally, I’m skeptical of that kind of thing, but we saw it confirmed in other reports like retail sales and car sales. Ford, for example, had a poor month in January, and we know that business is going well for them. The market usually doesn’t rise that much on a good jobless-claims report. So why was Thursday an exception? My guess is that it eased the fears of a broader macro downturn.

We had some mixed earnings for our Buy List this week. AFLAC had a solid report and reiterated its earnings for next year. Cognizant had very strong earnings last quarter and announced a 2-for-1 stock split, but CTSH merely met expectations. Meeting expectations, apparently, wasn’t expected. The stock sold off following the report. Should we ditch CTSH? Not at all. I’ll have more on that in a bit. Also, one of the biggest news stories this week was that Microsoft named their new CEO, and Bill Gates is stepping down as Chairman of the Board. I’ll give you my take. But first, let’s take a closer look at AFLAC’s earnings report.

AFLAC Is a Buy up to $68 per Share

On Tuesday, our favorite insurance stock, AFLAC ($AFL), reported that it quacked out a profit of $1.40 per share for the fourth quarter. That beat Wall Street’s forecast by one penny per share. But with a company like AFLAC, I honestly don’t care so much if they beat or miss earnings by a little bit. That’s not that important. This is a very well-run company, and it’s far more important to me to show what the general trend is.

As much as I like AFLAC, there’s a fundamental issue we need to consider when we look at its earnings. Since AFLAC does most of its work in Japan, its earnings can be greatly impacted by the yen/dollar exchange rate. Sometimes that works for them and sometimes it doesn’t; and lately, it hasn’t. The government in Japan has tried everything to get its economy moving, and the latest effort has been to weaken the yen. (It actually may be working.)

The downside for AFLAC is that the currency exchange ate up 18 cents per share in profit last quarter. That’s more than 11% of their bottom line. Despite the strong headwind, the company still managed to deliver a solid profit. Three months ago, AFLAC gave us a range for Q4 of $1.38 to $1.43 per share, so they’re right inside their own range.

Another problem AFLAC faces is that fixed-income yields are very low. That’s not good if you’re an insurance company. AFLAC has been working to revamp how it invests, and they’ve made it clear to investors that they’re going to try new areas. But the recent weakness we’ve seen in emerging markets could be weighing on AFL’s portfolio, though we don’t know yet exactly how much exposure they have to such markets.

The best news from AFLAC’s earnings report is that they reiterated their full-year guidance. A lot of investors downplay reiterations. Not me. It’s a good sign to hear from your company that all’s well. AFLAC sees operating earnings growing by 2% to 5% this year on a currency-neutral basis. The company said that if the yen were to remain at 97.54 to the dollar (its average for last year), then its earnings should range between $6.31 and $6.49 per share for 2014. So the stock is going for less than 10 times this year’s estimate.

Here’s an easier way to understand their forex exposure. Every move of one yen in the exchange rate translates to 3 to 3.25 cents per share in earnings for 2014. My take: There’s no need to worry about AFLAC. Business is going very well. I’m lowering my Buy Below on AFLAC to $68 per share.

Cognizant Technology Solutions to Split 2 for 1

I feel like I have to clear up some confusion about this week’s earnings report from Cognizant Technology Solutions ($CTSH). The shares fell after the report, and the behavior of traders should never surprise us. But this time, it was truly bizarre. The truth is that Cognizant had an excellent fourth quarter.

Let’s break down the math. For Q4, Cognizant earned $1.06 per share, which matched Wall Street’s forecast. Revenues rose 20.9% to $2.36 billion, which again matched the Street. Let’s be clear that both figures represent very strong growth.

For the first quarter, Cognizant sees earnings rising to $1.18 per share on revenue of $2.42 billion. Both numbers hit forecasts on the nose. Bear in mind that Cognizant earned 93 cents per share for last year’s Q1. So we’re talking about growth from 93 cents to $1.18. There’s nothing disappointing about that.

For all of 2014, CTSH forecasts earnings of at least $5.02 per share and revenues of at least $10.3 billion. This is where we have our “miss.” Wall Street had been expecting 2014 earnings of $5.08 per share on revenue of $10.39 billion. Technically that’s a miss if we downplay the “at least” part. Again, no one who follows Cognizant should be surprised or disappointed by these numbers. It’s pretty much what you would expect—more strong growth. To add some context, CTSH earned $4.38 per share last year and $3.74 per share in 2012. Yet the stock dropped 4.3% on Wednesday (though it gained back half that on Thursday).

The other news was that Cognizant announced a 2-for-1 stock split that will take effect next month. This will be their first split in more than six years. I’m not a strict value investor. I think there are times when it’s appropriate to pay a premium for growth, and Cognizant is just such an example. Right now, shares of CTSH are going for 19 times the company’s guidance for this year. Given their growth, that’s a good value. Cognizant Technology Solutions remains a buy up to $104 per share. The split is expected to happen in the first week of March. I’ll remind you as we get closer.

28 Straight Years of Double-Digit Growth at Fiserv

After the closing bell on Wednesday, Fiserv ($FISV) reported Q4 earnings of 79 cents per share, which was one penny below expectations. Quarterly revenues rose 10.3% to $1.26 billion, which matched forecasts. This was only our second earnings miss this season; Moog was the first (11 beats, two misses and one in-line so far).

Jeffery Yabuki, Fiserv’s CEO, said, “Our fourth-quarter performance capped off a strong year of delivering on our financial commitments, including our 28th consecutive year of double-digit adjusted-earnings-per-share growth.” That’s an astounding achievement.

In last week’s issue, I said that Wall Street’s estimate for 2014 for Fiserv might be too high. I’m happy to say I was wrong. Fiserv sees EPS this year ranging between $3.28 and $3.37 per share. Wall Street was at $3.34, so they’re within range.

For all of 2013, Fiserv made $2.99 per share, compared with $2.54 in 2012 (that’s adjusting for December’s split). Going by Thursday’s closing price, FISV is trading between 16.3 and 16.7 times this year’s earnings estimate. I’m going to drop our Buy Below down to $59 per share. Fiserv remains a very good buy.

Satya Nadella Takes Over at Microsoft

On Tuesday, Microsoft ($MSFT) announced that Satya Nadella will be its new CEO. There had been a lot of speculation on who would follow Steve Ballmer. There had even been some thoughts that Ford’s Alan Mulally would take the job. Fortunately for us, he’s staying at Ford.

Nadella is a very impressive candidate. He’s been at MSFT for 22 years, and he’s the former EVP of their Cloud and Enterprise Group. Interestingly, Bill Gates is stepping down as Chairman of the Board and will be taking on the role of “technology advisor.” John Thompson, an independent director, will take over as Chairman of the Board.

I can’t say yet whether this is good or bad news for Microsoft, but the market seems pleased that the speculation game is over. Shares of MSFT climbed after Nadella’s announcement. I like MSFT as an investment, but it’s clear that the company is shifting to a new phase. It’s no longer the high-growth company it was, and therefore, it shouldn’t command the high earnings multiples that it used to.

I think we’re seeing Microsoft gradually evolve into a service company that makes most of its money by working with corporate clients. This is a more stable path for them. We have to remember that Microsoft generates a very large cash flow. Fifteen years ago, it would have seemed bizarre to highlight MSFT’s generous dividend yield, but we can today. The shares currently yield 3.1%, which is well above average. Microsoft continues to be a good buy up to $40 per share.

That’s all for now. We don’t have any Buy List earnings reports next week, but DirecTV ($DTV) and Express Scripts ($ESRX) report the week after next. This Wednesday, we’ll get a report on the Federal Budget. The news on the deficit has been encouraging lately. Or more accurately, the bad news hasn’t been quite as severe. On Thursday, we’ll get a report on retail sales. This sector has been weak lately, and it looks to be an overreaction. Even traders are getting the hint. Shares of Ross Stores ($ROST) rallied strongly on Thursday, even though there was no news. Then on Friday, it’s Valentine’s Day, and we’ll get the report on Industrial Production. (There’s a sentence you don’t get to type very often.) Be sure to keep checking the blog for daily updates. I’ll have more market analysis for you in the next issue of CWS Market Review!

– Eddy

-

-

Archives

- May 2025

- April 2025

- March 2025

- February 2025

- January 2025

- December 2024

- November 2024

- October 2024

- September 2024

- August 2024

- July 2024

- June 2024

- May 2024

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- July 2019

- June 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- May 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- July 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- March 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- July 2016

- June 2016

- May 2016

- April 2016

- March 2016

- February 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- July 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- April 2015

- March 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- December 2014

- November 2014

- October 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

- July 2014

- June 2014

- May 2014

- April 2014

- March 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- July 2013

- June 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- August 2012

- July 2012

- June 2012

- May 2012

- April 2012

- March 2012

- February 2012

- January 2012

- December 2011

- November 2011

- October 2011

- September 2011

- August 2011

- July 2011

- June 2011

- May 2011

- April 2011

- March 2011

- February 2011

- January 2011

- December 2010

- November 2010

- October 2010

- September 2010

- August 2010

- July 2010

- June 2010

- May 2010

- April 2010

- March 2010

- February 2010

- January 2010

- December 2009

- November 2009

- October 2009

- September 2009

- August 2009

- July 2009

- June 2009

- May 2009

- April 2009

- March 2009

- February 2009

- January 2009

- December 2008

- November 2008

- October 2008

- September 2008

- August 2008

- July 2008

- June 2008

- May 2008

- April 2008

- March 2008

- February 2008

- January 2008

- December 2007

- November 2007

- October 2007

- September 2007

- August 2007

- July 2007

- June 2007

- May 2007

- April 2007

- March 2007

- February 2007

- January 2007

- December 2006

- November 2006

- October 2006

- September 2006

- August 2006

- July 2006

- June 2006

- May 2006

- April 2006

- March 2006

- February 2006

- January 2006

- December 2005

- November 2005

- October 2005

- September 2005

- August 2005

- July 2005

Eddy Elfenbein is a Washington, DC-based speaker, portfolio manager and editor of the blog Crossing Wall Street. His

Eddy Elfenbein is a Washington, DC-based speaker, portfolio manager and editor of the blog Crossing Wall Street. His