-

Roubini’s Real Track Record

Posted by Eddy Elfenbein on October 11th, 2010 at 4:13 pmI’m glad to see Charles Gasparino’s column on Nouriel Roubini’s overhyped reputation:

A closer inspection of Roubini’s record shows that while he was predicting doom and gloom for the US in 2004, his initial call had nothing to do with a runaway housing bubble.

Rather he argued that the Bush Administration was racking up massive deficits to foreign investors, namely the Chinese, and that the Chinese would scale back on their purchases of US debt, causing interest rates to spike and the dollar to decline in value, resulting in “financial trainwrecks for the US economy in a matter of a couple of years.”

Sounds good, but the problem with the theory is that it didn’t happen.

While I’m as worried as anyone else about the Chinese financing US domestic spending, it should be noted that there’s little sign that they’re about to stop, even with the Obama administration making President Bush look like a deficit hawk.

Based on my research, it wasn’t until about August 2006 that Roubini began talking about a housing crisis, and he was hardly alone. Several economists and investors, from John Paulson to Stan Druckenmiller and around this time Goldman Sachs, were also predicting the housing decline.

Roubini, for his part, wasn’t available for comment, but a spokesman said in a statement that he has “built a strong and rapidly growing business,” and has more than “1,000 institutional clients.”

Maybe so, but how do they feel about his call on the price of gold? Last year he predicted that the rising price of gold was in fact a bubble, just like the housing one a few years earlier, and like housing, it would burst as well. But as we all know gold prices remain strong.

For the record, I think Roubini is a very smart guy and well worth listening to. But I don’t believe he predicted the financial crisis.

There are currently 837,000 Google matches for the search “predicted the financial crisis.” The top one, as it turns out, was written by me.

If so many people saw it coming, it’s a wonder how it happened.

-

The Federal Reserve’s Educational Links

Posted by Eddy Elfenbein on October 11th, 2010 at 3:55 pmThe Federal Reserve has a number of education resources, often in the form of online games. Here’s a quick rundown:

The Federal Reserve’s Kid’s Page

Great Economists Treasure Hunt

Peanuts & Crackerjacks, the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston’s interactive baseball game

Finally, are you looking for a Fed membership form? I got ya right here.

-

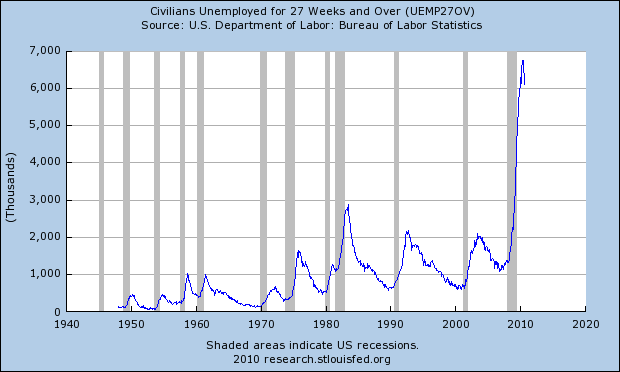

Scary Jobs Chart

Posted by Eddy Elfenbein on October 11th, 2010 at 1:55 pmThe number of Americans who have been unemployed 27 weeks or longer:

-

No Empirical Support for the 200-DMA?

Posted by Eddy Elfenbein on October 11th, 2010 at 1:13 pmThis is from the Q&A section of the Fama/French Forum:

Some researchers argue that a market timing strategy based on buy/sell signals generated by a 50- or 200-day moving average offers a more appealing combination of risk and return than a buy-and-hold approach. What is your view?

EFF/KRF: An ancient tale with no empirical support.

That’s simply not true. This is what I wrote about the 200-DMA last year:

One of the quick-and-dirty tools used by technical analysts is to see where a stock or index is compared with its average price over the past 200 days. This is an easy way to get a read of a stock’s momentum.

Yesterday was a big day for the 200DMA world. The S&P 500 closed above its 200DMA for the first time since December 26, 2007. That closed out the index’s longest run below its 200DMA according to my records which go back to 1932.

That streak, however, is still well short of the longest run above the 200DMA which ran from November 1953 all the way to May 1956. Since the index has gone up over time, the “above” streaks tend to be longer than the “below” streaks.

On November 20, 2008, the S&P was a stunning 39.6% below its 200DMA. That’s the biggest discount on my records. The only thing that comes close is the reading from this past March.

So does the 200DMA work? The evidence suggests that it’s a pretty good indicator of future price performance. When the S&P 500 has been below the 200DMA, it’s dropped a total of about 20% over the equivalent of 27 years. In other words, the S&P 500 has been below its 200DMA about one-third of the time.

Historically, the best time to invest has been when the S&P is less than 1.7% below the 200DMA.

When the index is above the 200DMA, well, then everything looks much brighter. All of the market’s gains and then some have happened when we’re above the 200DMA which occurs about two-thirds of the time.

The market seems to like nearly every point of being above the 200DMA. Danger only clicks in when the S&P 500 is over 17.5% above the 200DMA which is a very high reading.

This issue isn’t whether the 200-DMA works or not. It’s a dumb rule, but it reveals an important truth about investing: the market likes trends. If the market is going in one direction, it has a much better than average chance of staying in that direction.

-

Happy Columbus Day

Posted by Eddy Elfenbein on October 11th, 2010 at 11:31 amColumbus Day is unusual for Wall Street because the bond market is closed yet the stock market is open. I have absolutely no idea why. I believe the Columbus was financed by the original Sovereign Wealth Fund, with actual sovereigns!

Three months ago, I said Intel (INTC) would beat its earnings report and I was right. Then last month, I said Bed Bath & Beyond (BBBY) could earn as much as 70 cents per share. That was a gutsy call since it was well above Wall Street’s expectations. Nevertheless, I was right again.

Now Intel is due to report earnings again tomorrow. The Street’s current estimate is for 50 cents per share, and this time I’m not expecting much of an earnings beat, if any at all. Fifty cents per share sounds about right.

The stock that I think is a good candidate for an earnings beat is JPMorgan Chase (JPM). I hope to post more of my thoughts on that this week. The bank will report earnings on Wednesday. Except for Intel, the earnings reports for the rest of our Buy List won’t start coming in until next week.

-

Morning News: October 11, 2010

Posted by Eddy Elfenbein on October 11th, 2010 at 7:26 amTreasury 2-, 5-Year Yields Decline to Record Lows on Outlook for Fed Buys

Richard Bernstein to Manage Stock Mutual Fund for Eaton Vance

Everyone into the Pool: How to Invest in Twitter

Happy Fifth Blogiversary to Abnormal Returns

European Stocks Edge Higher Amid QE Hopes

Wage China Currency War With Light Armor, Investors Say

Foreclosure Freeze May Sideline U.S. Homebuyers as Legal Worry Cuts Sales

-

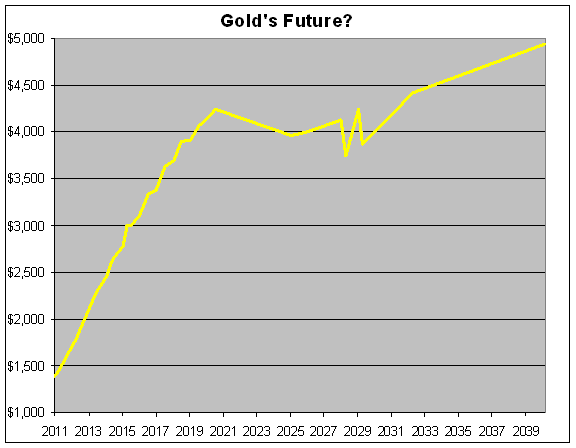

What’s the Future for Gold?

Posted by Eddy Elfenbein on October 10th, 2010 at 10:44 pmI took the current TIPs yield curve and plugged it into my Gold Model to see what the future may hold for gold:

Now let me add several major caveats.

This is not in any way my forecast for where gold will go. The model I made is just that, a model. Or more specifically, it’s a model of how a better model might look.

As to the specific constants I used (eight for leverage and 2% for equilibrium), those are just working estimates. If those numbers are changed even slightly, the chart above looks very different.

Of course, the numbers can also lead to an entirely different conclusion: that TIPs are far too high. (A real return of 0% for six years? No thank you!)

We should also bear in mind that estimates for the future based on what we know today are notoriously poor. In 1999, the TIP that was maturing in 2002 was showing a real yield of 3.5% to 4%.

The real takeaway is that the market thinks real rates will remained subdued for a long time. It won’t be another 10 years until real rates get back to normal.

-

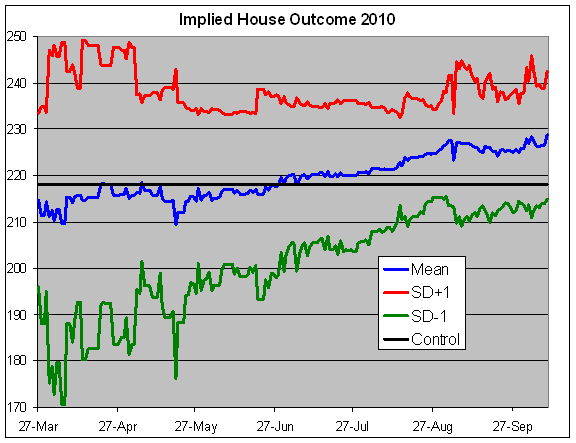

Implied Markets — House Elections

Posted by Eddy Elfenbein on October 10th, 2010 at 8:39 pmOne of the topics in finance I find most fascinating is implied prices. This is when we take the prices of two or more assets and use them to find an “implied” price for another asset.

For example, that’s what the VIX is all about—implied volatility. In the options pricing model, volatility is one of the variables. So what we can do is take the current market price of an index option and work backward to see what number the market has given to the volatility variable.

I’ve noticed that we can also find some implied prices in futures markets on current events listed at Intrade. (Note: This is not — repeat, not — a political post. It’s about implied markets.)

Here’s an example. The current price for the Republicans to win control of Congress is 78.2. That’s a gain of 40 seats. There’s another contract for the Republicans to gain 50 seats. The latest price for that contract is 52.0. (Second note: I don’t take these markets too seriously. I simply see them as entertainment.)

A 78.2% probability translates to +0.779 standard deviations above the mean (that’s NORMSINV in Excel). A 52% probability translates to +0.050 standard deviations above the mean. The difference between those must be 10 seats, so one full implied standard deviation works out to 13.7 seats.

From there we can see that the mean is a gain of 50.7 seats. With the GOP currently holding 178 seats, the market therefore currently expects the GOP to hold 228.7 seats after the election.

I downloaded the historical numbers and here’s what the market’s implied outcome is for the election. The black line is 218 which is a majority. The blue line is the implied mean for the GOP. The red line is one standard deviation above the mean and the green line is one standard deviation below.

-

Remembrance of Stocks Past

Posted by Eddy Elfenbein on October 10th, 2010 at 3:57 pmOne of my rules of investing is: “Never worry about what stocks do after you’ve sold them.” The stocks aren’t thinking of you, so why should you think of them? That’s a wise rule. Nevertheless, I’m ignoring it for the moment.

Each year, I add and delete five stocks to my 20-stock Buy List. As it turns out, the stocks I removed from the Buy List at the beginning of this year have done far better than their replacements.

Here are the five new stocks:

Company Ticker Symbol Price on 31-Dec Price on 8-Oct Profit Gilead GILD $43.27 $36.33 -16.04% Intel INTC $20.40 $19.52 -4.31% Johnson & Johnson JNJ $64.41 $63.23 -1.83% Reynolds American RAI $52.97 $58.73 10.87% Wright Express WXS $31.86 $36.36 14.12% Average 0.56% Here are the five stocks I cut:

Company Ticker Symbol Price on 31-Dec Price on 8-Oct Profit Ampehnol APH $46.18 $49.25 6.65% Cognizant Technology CTSH $45.33 $64.20 41.63% Donaldson DCI $42.54 $47.39 11.40% Danaher DHR $37.60 $41.39 10.08% FactSet Research FDS $65.87 $82.67 25.50% Average 19.05% Even though I limit myself to changing the portfolio by 25% just once per year, even that was too much. If I had made no changes at all, the Buy List would be up 11.59% instead of 6.97%.

OK, I’m going back to enforcing my rule. If anyone needs me, I’ll be pretending CTSH isn’t up 41% YTD.

-

Gold Model — Reader Response

Posted by Eddy Elfenbein on October 9th, 2010 at 4:50 pmHere’s a thoughtful email I received in response to my gold model:

I read your piece on your gold model and thought it was very good – really dead on. I think, however, you have the relationship somewhat backwards on two counts.

First, the dollar derives its value from its relationship to gold. So instead of the dollar price of an ounce of gold, it should be thought of as the gold price of a single dollar. (For instance, the current of gold price of single US dollar is presently about 1/1345th of an ounce of gold)

Second, on this basis, the relationship is somewhat clearer: when the purchasing power of an ounce of gold rises (i.e., when an ounce of gold commands more dollars) interest rates will be low; and, when the purchasing power of a an ounce of gold falls (i.e., when gold commands fewer dollars the interest rate will be high.

In the days of the gold standard, this meant when prices, denominated in gold backed money, fell, interest rates fell – for instance, during periods of depressions. This would also be the period when the purchasing power of gold backed money was at its highest.

When prices, denominated in gold backed money rose, interest rates also rose – for instances during periods of rapid expansion. This would have been the period when the purchasing power of gold backed money was at its lowest.

Under the gold standard, the purchasing power of money fell during expansions, or what is the same thing, prices rose. And, interest rates rose with prices. The purchasing power of money rose during depressions, or what is the same thing, prices fell. And interest rates fell with prices.

So, what you have shown is that the Gibson Paradox continues to work even in the absence of gold backed money. It did not disappear. It expresses itself through national currencies and thus reveal the underlying state of the real economy through this operation.

When the “dollar price” of gold is rising, it is likely that we are in a depression in the real economy. Hence, real interest rates should be at their lowest. And, when the “dollar price” of gold is falling, it is likely we are in a period of expansion. Hence, interest rates should be at their highest.

Both the movement of gold prices and interest rates are determined by the expansion or contraction of the real economy, and by an inverse relation between them. When the real economy is expanding, gold prices will fall and interest rates will be higher. When the real economy is contracting, gold prices will rise, and interest rates will be lower.

What rising gold prices are telling us today, and for the last decade, is that we are in a depression in the real economy – one that has lasted about a decade at present, and shows no signs of ending as yet. Layered over this real economy depression has been two monetary recessions – the first in 2001, and the present one; with, one period of monetary expansion between them.

-

-

Archives

- May 2025

- April 2025

- March 2025

- February 2025

- January 2025

- December 2024

- November 2024

- October 2024

- September 2024

- August 2024

- July 2024

- June 2024

- May 2024

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- July 2019

- June 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- May 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- July 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- March 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- July 2016

- June 2016

- May 2016

- April 2016

- March 2016

- February 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- July 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- April 2015

- March 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- December 2014

- November 2014

- October 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

- July 2014

- June 2014

- May 2014

- April 2014

- March 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- July 2013

- June 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- August 2012

- July 2012

- June 2012

- May 2012

- April 2012

- March 2012

- February 2012

- January 2012

- December 2011

- November 2011

- October 2011

- September 2011

- August 2011

- July 2011

- June 2011

- May 2011

- April 2011

- March 2011

- February 2011

- January 2011

- December 2010

- November 2010

- October 2010

- September 2010

- August 2010

- July 2010

- June 2010

- May 2010

- April 2010

- March 2010

- February 2010

- January 2010

- December 2009

- November 2009

- October 2009

- September 2009

- August 2009

- July 2009

- June 2009

- May 2009

- April 2009

- March 2009

- February 2009

- January 2009

- December 2008

- November 2008

- October 2008

- September 2008

- August 2008

- July 2008

- June 2008

- May 2008

- April 2008

- March 2008

- February 2008

- January 2008

- December 2007

- November 2007

- October 2007

- September 2007

- August 2007

- July 2007

- June 2007

- May 2007

- April 2007

- March 2007

- February 2007

- January 2007

- December 2006

- November 2006

- October 2006

- September 2006

- August 2006

- July 2006

- June 2006

- May 2006

- April 2006

- March 2006

- February 2006

- January 2006

- December 2005

- November 2005

- October 2005

- September 2005

- August 2005

- July 2005

Eddy Elfenbein is a Washington, DC-based speaker, portfolio manager and editor of the blog Crossing Wall Street. His

Eddy Elfenbein is a Washington, DC-based speaker, portfolio manager and editor of the blog Crossing Wall Street. His