-

Schumpeter’s Moment

Posted by Eddy Elfenbein on May 29th, 2009 at 9:16 amCarl Schramm has a good article on Joseph Schumpeter in today’s WSJ. Here’s a taste:

From Schumpeter’s vantage point, capitalism’s very success allows rich societies to use government to relax the impersonal rules that govern markets, creating new rules that buffer citizens from the rigors of risk-taking and failure. In that sense, government invents for itself the task of mediating market outcomes. Schumpeter had seen the dangers of this play out in Bismarck’s conception of Prussia’s welfare state. In the face of the Marxist threat, the elite secured its position by causing government to dispense social benefits. Political entrenchment, not charity, had motivated Bismarck. When distorted in such a way, free-market capitalism is seen to suppress — rather than to encourage — social and economic mobility.

Since the New Deal, Americans have come to see government as somehow the ultimate protector of their financial welfare. In reality, though, the evidence of the U.S. government behaving in this way during the New Deal is thin to say the least. Although it is largely forgotten now, much of the government’s action during the Depression actually had a marginal impact on individual lives. Monetary expansion and technological innovation boosted the economy, while the “second” depression of 1937-1938 is widely understood as having been induced by Roosevelt’s attempt to manipulate credit markets. -

Ted Tuner: AOL/TWX Meger “Better than Sex”

Posted by Eddy Elfenbein on May 29th, 2009 at 8:41 amMark Hulbert writes on the dissolution of AOL and Time Warner’s nine-year marriage. I had never heard this quote before but Ted Turner said that the deal was “better than sex.” He was married to Jane Fonda at the time.

-

Exceedingly Bizarre Marx Brothers Trivia That I Must Be the Only One Interested In

Posted by Eddy Elfenbein on May 28th, 2009 at 9:17 pmI noticed this story today that the two surviving Dionne quintuplets just turned 75. That’s whom Chico is referring to in the classic “contract” scene from A Night at the Opera (0:47 to 1:02):

-

The 90s Finally End

Posted by Eddy Elfenbein on May 28th, 2009 at 10:03 amTime Warner to Spin Off AOL

Time Warner says its board has approved plans to spin off AOL, the company’s lagging Internet unit.

The New York company, which owns 95 percent of AOL, said Thursday it will buy out Google’s 5 percent stake during the third quarter and spin the unit off to Time Warner shareholders.

The long-anticipated move is expected to be completed around the end of the year.

AOL and Time Warner combined in 2001 in a deal they said would produce a powerful marriage of content and the Internet. But it produced big losses instead.

In a statement, Time Warner Chief Executive Jeff Bewkes said, “We believe AOL will then have a better opportunity to achieve its full potential as a leading independent Internet company.”

Time Warner shares rose almost 3 percent in premarket trading.For a good laugh, here’s the CNN story announcing the merger more than nine years ago.

In a stunning development, America Online Inc. announced plans to acquire Time Warner Inc. for roughly $182 billion in stock and debt Monday, creating a digital media powerhouse with the potential to reach every American in one form or another.

With dominating positions in the music, publishing, news, entertainment, cable and Internet industries, the combined company, called AOL Time Warner, will boast unrivaled assets among other media and online companies.

The merger, the largest deal in history, combines the nation’s top internet service provider with the world’s top media conglomerate. The deal also validates the Internet’s role as a leader in the new world economy, while redefining what the next generation of digital-based leaders will look like.

“Together, they represent an unprecedented powerhouse,” said Scott Ehrens, a media analyst with Bear Stearns. “If their mantra is content, this alliance is unbeatable. Now they have this great platform they can cross-fertilize with content and redistribute.”

-

The Most Useless Index of the Financial Crisis

Posted by Eddy Elfenbein on May 28th, 2009 at 9:03 amDaniel M. Harrison awards the honor of most useless index of the financial crisis to Dow Jones and their Economic Stimulus Index:

In other words, the DJ Economic Stimulus Index aims to capture how well bailout recipients are faring among investors. That in turn is supposed to be some sort of indicator of U.S. economic momentum.

But there are two factors that make this index really redundant, and even dangerous to use.

Firstly, as I discussed yesterday, companies’ capitalizations are more or less irrelevant as a sign of economic growth unless consumer spending is being directed at the products these firms manufacture. Just because there’s a bunch of investors looking to get in on beaten-down share prices, that doesn’t mean that economic conditions in the U.S. are fundamentally getting any better.

For example, higher share prices among banks and automakers says nothing about lending conditions, home foreclosure rates, auto sales or any of the other indicators you would traditionally associate with economic growth.

Instead of tracking share prices, a really useful economic stimulus index would monitor the earnings of the top 50 stocks which are recipients of the bailout funds. Then we’d have a much better idea of how these companies are performing.

But most of all: why does anyone want an index tracking these companies when the stock market is pretty much moving in tandem with their trading patterns these days anyway? Since the stimulus packages were put in place, you could just as easily have glanced at any of the major indexes on pretty much any day and concluded how GM, Bank of America, Citigroup, or Ford are faring.Read the whole thing.

Update: S&P has upped the competition. They have a new index that follows companies that adhere to Sharia Islamic law. In other words, no alcohol, pork or tobacco. Best of all…it’s Canadian! -

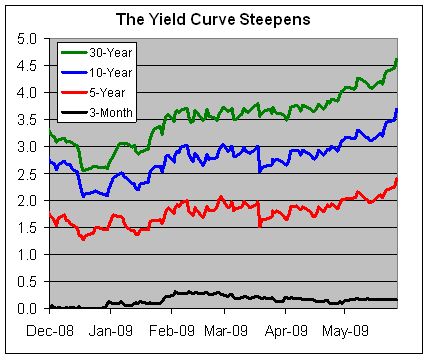

The Yield Curve Steepens

Posted by Eddy Elfenbein on May 28th, 2009 at 8:32 amThe widening yield curve is the most important recent development on Wall Street. Long-term interest rates had already been creeping upward, but they started to break out after mid-May.

Tyler Durden notes that the spread between the 2- and 10-year yield is now at an all-time record. Arnold Kling says that the short-term effect of stimulus package is negative.

Here’s a look at the yield curve since December.

-

South Wins Civil War

Posted by Eddy Elfenbein on May 28th, 2009 at 8:07 amThe WSJ reports:

Some laid-off workers in the financial-services industry are making a novel pitch for jobs: They are offering to work for nothing.

“People have been sending their CVs to our New York office saying, ‘hire me for free for six months.’” says Christophe Chouard, head of sales at French fund of hedge funds manager HDF Finance. “The CVs we are receiving are pretty good. These people are saying, ‘just let me show you what I can do.’”

Headhunters said redundant financial-services staffers, particularly those working on institutional sales, were keen to keep their knowledge of the industry and their contacts up to date when they weren’t earning.

It isn’t just the prospect of cheap labor that might appeal to companies. The chief executive of one asset-management company said it was sad to see rows of empty desks–fully equipped but vacated–as a result of cost cutting. -

Who Should Replace GM in the Dow?

Posted by Eddy Elfenbein on May 27th, 2009 at 8:52 pmI guess a 30-year Treasury bond makes the most sense.

Outside that, I’d vote for UPS (UPS). -

Why the Dow 36,000 Argument Doesn’t Work

Posted by Eddy Elfenbein on May 27th, 2009 at 2:26 pmFrom nine years ago, here’s my review of Dow 36,000:

Now that the Dow Jones Industrial Average has soared over 4,500 points since Alan Greenspan warned us of the market’s “irrational exuberance,” a mini-industry has evolved of publishing books that attempt to explain the “new market.” The latest addition to the genre is Dow 36,000 by James K. Glassman and Kevin A. Hassett, both of the American Enterprise Institute. To give you an idea of how crowded the field is becoming, two other books are titled Dow 40,000 and Dow 100,000.

Unfazed by the Dow’s stunning climb, mega-bulls Glassman and Hassett have developed their own theory as to why the market has risen so much and why it will continue to rise. Their theory isn’t the usual litany one hears from Wall Street bulls (demographics, triumph of capitalism). Instead, their “36,000” theory goes right to the heart of investment analysis by questioning one of its elemental suppositions: namely, the idea that investments in stocks should demand a premium over investments in bonds due to the riskier nature of stocks. This isn’t split hairs they’re taking on.

Reciting historical data, Glassman and Hassett show that over the long haul, there is no difference between the risks of stocks and Treasury bonds. Therefore, they reason, there should be no risk premium at all. The authors claim that with the risk premium excised from the market, the perfectly reasonable price, or PRP as they call it, for the Dow is 36,000 (more on that later). Mind you, they’re not merely saying the Dow will eventually hit this magic number sometime in the future. Instead, Glassman and Hassett claim that 36,000 is where the Dow ought to be right now. Or more precisely, that’s where the Dow should have been early this year when they started writing the book. Could they be onto something? At the time, the Dow was at 9000.

The Dow very well may head to 36K, but it will have little to do with Glassman and Hassett’s theory. Their theory is seriously flawed due to major methodological errors.

First, Glassman and Hassett err in their selection of an appropriate measure of risk for their purpose. The free market prices risk, just like it prices everything else. That price is included in the price of stocks. In order to measure risk, Glassman and Hassett should use a measurement that isolates risk from the price of stocks. They don’t do this. Instead, they compare the standard deviation of stock returns to the standard deviation of risk-free-bond returns. That’s a different animal. Sure enough, with progressively longer holding periods, stock returns’ standard deviations gradually get smaller. Upon realizing that at long term, the standard deviation of stock returns is the same as bond returns’, actually slightly less, Glassman and Hassett conclude that stocks are “no more risky” than Treasury bonds.

That’s a faulty conclusion. Even if the standard deviations are the same size, it doesn’t say anything about the risk that they’re looking for. The point is, that risk has still never been isolated: It’s inside those returns no matter how long term you go. The variability of risk’s part of all these returns may be diminishing as well. That can happen even if risk stays exactly the same size. With Glassman and Hassett’s method, we have no idea how big the risk inherent in stock ownership is.

Without all the mumbo-jumbo, think of two houses, identical in every way except one has a great view of the river, the other does not. How much does the river view cost? Easy. Compare the prices of the two homes, and the difference must be the price of the view. The fact that the prices paid may deviate from their own respective averages the same way, speaks nothing as to the price of the view. Glassman and Hassett are saying that since those deviations are the same, the river view is free.

Running with this assumption, Glassman and Hassett reason that since risk and reward are related, assets with the same risk will have the same return. Therefore, stocks and bonds will have the same returns. For this to happen, they claim, “the Dow should rise by a factor of four.” How do they get four?

Glassman and Hassett start with the “Old Paradigm” premise that bond returns plus a risk premium equals stock returns. With the risk premium “properly” removed, the yield on Treasuries—meaning their expected return—should be the same as the expected return for stocks. And that’s their dividend yield plus the dividend’s growth rate. So far, so good. Since the sum of these two is now about 1.5% above today’s Treasury yield, the yield on stocks needs to be adjusted downward in order to bring everything into balance. Specifically, it needs to drop from about 2% to 0.5%. With the yield dropping to one-fourth its previous level, stock prices will jump fourfold. Presto. That’s how we get from 9000 to 36000.

Not exactly. The authors have made another mistake. It’s impossible to have a one-time-only ratcheting down of the market’s dividend yield. The reason is that if long-term stock returns don’t change, as the authors do assume, a lower dividend yield will always create a commensurate increase in the dividend growth rate. As a result, there will always be a new higher dividend whose yield will always be in need of being notched back down. And as a result, the dividend growth rate will increase, and the cycle will continue ad infinitum. The correct conclusion from their model is not a one-time-only fourfold increase in stocks, but one-time-only infinite increase in stocks. This means the authors are actually insufficiently bullish and, moreover, they’ve mistitled their book.

Fortunately, the second half of the book is the more valuable by far. Once the authors stop making theories, they start making some sense. In this section, the authors discuss how investors can capitalize on the continuing market boom. The authors estimate the market has another three to five years perhaps before 36K is reached. In any case, their strategies are rather conservative: Buy and hold, diversify, don’t trade too much, don’t let market fluctuations rattle you, don’t time the market. All perfectly sound ideas and not specifically dependent on “Dow 36,000.”

Glassman and Hassett also give the names of stocks and mutual funds they like. There’s nothing wrong with their stocks in the realm of theory, but readers definitely ought to avoid the author’s so-called Perfectly Reasonable Prices, which invite comparison to the famous description of the Holy Roman Empire—not holy, not Roman, not an empire.

I’m not familiar with Kevin Hassett’s former work, but I’ve always liked James Glassman’s investing articles for The Washington Post. His articles are consistently incisive and informative. This book, however, is nothing of the sort. Dow 36,000 contains egregious errors and fallacious reasoning.

Still, I do admire their ambition. With this book, Glassman and Hassett challenged a well-entrenched perception of reality. Being that this perception underwrites trillions of dollars, it’s a very, very, very, well-entrenched perception. Glassman and Hassett lost, and they lost badly. Old paradigms die hard, but they do die.

-

Donaldson’s Earnings Plunge

Posted by Eddy Elfenbein on May 27th, 2009 at 1:16 pmDonaldson (DCI) is one of my favorite stocks. This company really should be better known. The problem holding them back is that their business is about as dull as you can get—filtration systems.

Still, the company has performed a remarkable feat. They’ve reported higher earnings for 19 straight years. Unfortunately, that’s all coming to an end this year.

For the first two quarter of this fiscal year (ending in July), Donaldson earned $1.03 a share which was a bit higher than the 95 cents a share from the same period last year.

The Q3 report came out yesterday and Donaldson earned just 35 cents a share which is a massive drop from the 57 cents a share last year. So for the first three quarters of this fiscal year, the company has made $1.37 a share compared with $1.52 from last year.

In November, Donaldson said they expect full-year EPS of $2.16 to $2.36. In February, they said you better make that $1.70 to $1.90. This confirms Elfenbein’s Investing Rule #174503B: One Earnings Warnings Leads to Another. Then yesterday, they said $1.55 to $1.70. They made $2.12 a share for all of 2008.

This is still a company I like a lot. Unfortunately, we’re in the worst part of its cycle right now. Even the best stocks will get slammed in order to please the market gods. I’m sticking with Donaldson but if you want to get in, you’ll probably see a better entry price in a few months.Year………….Sales……………..EPS

1990…………$422.9……………$0.19

1991…………$457.7……………$0.21

1992…………$482.1……………$0.23

1993…………$533.3……………$0.26

1994…………$593.5……………$0.30

1995…………$704.0……………$0.37

1996…………$758.6……………$0.42

1997…………$833.3……………$0.50

1998…………$940.4……………$0.57

1999…………$944.1……………$0.66

2000…………$1,092.3…………$0.76

2001…………$1,137.0…………$0.83

2002…………$1,126.0…………$0.95

2003…………$1,218.3…………$1.05

2004…………$1,415.0…………$1.18

2005…………$1,595.7…………$1.27

2006…………$1,694.3…………$1.55

2007…………$1,918.8…………$1.83

2008…………$2,232.5…………$2.12

-

-

Archives

- May 2025

- April 2025

- March 2025

- February 2025

- January 2025

- December 2024

- November 2024

- October 2024

- September 2024

- August 2024

- July 2024

- June 2024

- May 2024

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- July 2019

- June 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- May 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- July 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- March 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- July 2016

- June 2016

- May 2016

- April 2016

- March 2016

- February 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- July 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- April 2015

- March 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- December 2014

- November 2014

- October 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

- July 2014

- June 2014

- May 2014

- April 2014

- March 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- July 2013

- June 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- August 2012

- July 2012

- June 2012

- May 2012

- April 2012

- March 2012

- February 2012

- January 2012

- December 2011

- November 2011

- October 2011

- September 2011

- August 2011

- July 2011

- June 2011

- May 2011

- April 2011

- March 2011

- February 2011

- January 2011

- December 2010

- November 2010

- October 2010

- September 2010

- August 2010

- July 2010

- June 2010

- May 2010

- April 2010

- March 2010

- February 2010

- January 2010

- December 2009

- November 2009

- October 2009

- September 2009

- August 2009

- July 2009

- June 2009

- May 2009

- April 2009

- March 2009

- February 2009

- January 2009

- December 2008

- November 2008

- October 2008

- September 2008

- August 2008

- July 2008

- June 2008

- May 2008

- April 2008

- March 2008

- February 2008

- January 2008

- December 2007

- November 2007

- October 2007

- September 2007

- August 2007

- July 2007

- June 2007

- May 2007

- April 2007

- March 2007

- February 2007

- January 2007

- December 2006

- November 2006

- October 2006

- September 2006

- August 2006

- July 2006

- June 2006

- May 2006

- April 2006

- March 2006

- February 2006

- January 2006

- December 2005

- November 2005

- October 2005

- September 2005

- August 2005

- July 2005

Eddy Elfenbein is a Washington, DC-based speaker, portfolio manager and editor of the blog Crossing Wall Street. His

Eddy Elfenbein is a Washington, DC-based speaker, portfolio manager and editor of the blog Crossing Wall Street. His