-

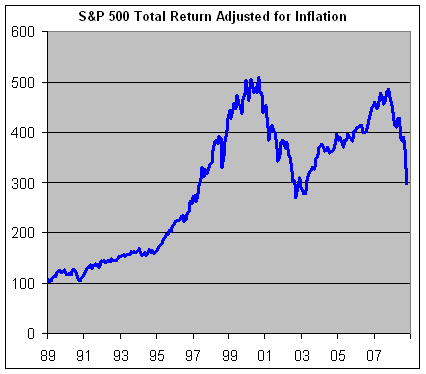

S&P 500 Total Return Adjust for Inflation

Posted by Eddy Elfenbein on November 3rd, 2008 at 2:33 pmHere’s a look at how the S&P 500 has done including dividends and adjusted for inflation:

Historically, the market’s real total return has been about 7% a year. The means it doubles every ten years, but in the last ten years, investors haven’t made a dime. -

Vote Tomorrow and Get a Free Cup of Coffee at Starbucks

Posted by Eddy Elfenbein on November 3rd, 2008 at 1:29 pm -

The Fall of AIG

Posted by Eddy Elfenbein on November 3rd, 2008 at 12:44 pmWhen economic historians pick through the rubble of the Panic of 2008, there will be lots of difficult questions to answers. The one I will never understand is how AIG (AIG) collapsed.

Sheesh…how frickin stupid do you have to be to ruin AIG?

Lehman and Bear I get, but let’s face it, insurance isn’t that difficult to make money in. Some companies make a lot more than others, but making a profit is a pretty easy concept in insurance. Manage your risk and charge more than you pay. Repeat.

Sure, a disaster can hurt or ruin your business, but you have to be an idiot to ruin it from the inside. Sure enough, that’s what AIG did. Actually, their insurance business was doing well. It was their idiotic forays in the CDS market that sank the company.

The Wall Street Journal looks at AIG’s collapse and Gary Gorton, the finance professor at the center of it all:AIG’s credit-default-swaps operation was run out of its AIG Financial Products Corp. unit, which had offices in London and Wilton, Conn. In essence, AIG sold insurance on billions of dollars of debt securities backed by everything from corporate loans to subprime mortgages to auto loans to credit-card receivables. It promised buyers of the swaps that if the debt securities defaulted, AIG would make good on them. AIG executives, not Mr. Gorton, decided which swaps to sell and how to price them.

The swaps expose AIG to three types of financial pain. If the debt securities default, AIG has to pay up. But there are two other financial risks as well. The buyers of the swaps — AIG’s “counterparties” or trading partners on the deals — typically have the right to demand collateral from AIG if the securities being insured by the swaps decline in value, or if AIG’s own corporate-debt rating is cut. In addition, AIG is obliged to account for the contracts on its own books based on their market values. If those values fall, AIG has to take write-downs.

Mr. Gorton’s models harnessed mounds of historical data to focus on the likelihood of default, and his work may indeed prove accurate on that front. But as AIG was aware, his models didn’t attempt to measure the risk of future collateral calls or write-downs, which have devastated AIG’s finances.

The problem for AIG is that it didn’t apply effective models for valuing the swaps and for collateral risk until the second half of 2007, long after the swaps were sold, AIG documents and investor presentations indicate. The firm left itself exposed to potentially large collateral calls because it had agreed to insure so much debt without protecting itself adequately through hedging.

The credit crisis hammered the markets for debt securities, sparking tough negotiations between AIG and its trading partners over how much more collateral AIG should have to post. Goldman Sachs Group Inc., for instance, has pried from AIG $8 billion to $9 billion, covering virtually all its exposure to AIG — most of it before the U.S. stepped in.

Such payments continued after the government bailout. AIG already has borrowed $83.5 billion from the Federal Reserve, a little more than two-thirds of the $123 billion in taxpayer loans made available to AIG so far. In addition, AIG affiliates recently obtained from the government as much as $21 billion in short-term loans called commercial paper. Much of the $83.5 billion has been used to meet the financial obligations of the financial-products unit. If turmoil in the markets causes prices of many assets to fall further, the government might have to cough up more money to help keep AIG afloat. Cutting it off would risk renewing the market upheaval the policy makers have struggled to tame. -

Sysco’s Earnings

Posted by Eddy Elfenbein on November 3rd, 2008 at 12:22 pmEven for a defensive stock, Sysco (SYY) tends to be pretty defensive. The quarterly numbers tend not to fluctuate much. For the September quarter, the company’s fiscal first quarter, Sysco earned 46 cents a share, which was a penny below Street estimates. Last year, it earned 43 cents a share.

While the S&P 500 is off by about 34% for the year, Sysco is “only” down around 18%. That’s a rough year but it’s a lot better than most. Sysco is currently going for about 13 times next year’s earnings. -

The Real Bubble

Posted by Eddy Elfenbein on November 3rd, 2008 at 10:09 amArnold Kling spots the real bubble. It’s not finance, but in macroeconomics:

I would not be surprised to see unorthodox theories of control gain traction. Perhaps, to justify current policy trends, a theory that socialized investment is necessary for stability.

To me. the logical thing for the economics profession to do is admit that we are nowhere near understanding what is happening. However, taking that position will not get you invited to panels.

I think that there are two questions. First, what are the generic causes and consequences of bubbles? Second, why did the specific bubble in real estate and mortgage finance occur? The first question is harder. But I would say that 99 percent of the economics profession cannot even correctly answer the second. -

The 28th Amendment

Posted by Eddy Elfenbein on October 31st, 2008 at 10:43 pmHow large should a representative assembly be relative to its population? My idea is that it should be the pi root of the population. I figure that since the Greeks invented democracy, it should have some connection to the ancients.

Personally, I’d like to see this as a constitutional amendment (called the Elfenbein Amendment) that will formally determine the size of the U.S. House of Representatives, although I don’t believe it’s required. I think a simple law will do.

I ran the idea passed John Derbyshire, and he had the best response—pi is appropriate given that the place is irrational.

I’ve attached a spreadsheet showing what the historical root has been, and it’s often hovered around 3.14.

-

Voting During a Recession

Posted by Eddy Elfenbein on October 31st, 2008 at 9:53 pmThis will be the first time Americans will be voting for president during a recession in 48 years. The National Bureau of Economic Research hasn’t officially declared this a recession, but I’m assuming they’re mark the beginning of this current recession as starting sometime in the second quarter. If I had to guess, I’d say May or June.

NBER has the dates of recessions going back to 1854 and this is the longest stretch without a recession election.

Here are the previous recession elections:

1860

1876

1884

1896

1900

1920

1932

1948

1960

Several of those are now viewed as pretty historic elections. Notice how often there was a change of parties. It’s also pretty amazing how Harry Truman pulled it off 60 years ago. -

The Nouriel Roubini Halloween Facemask

Posted by Eddy Elfenbein on October 31st, 2008 at 12:46 pmBe afraid.

Be very afraid. -

Charlie Gasparino Gets Philosophical…I Think

Posted by Eddy Elfenbein on October 30th, 2008 at 8:44 pm -

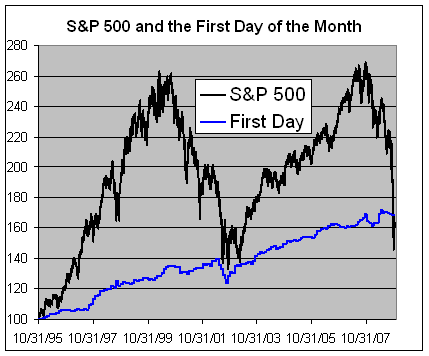

The First Trading Day of the Month

Posted by Eddy Elfenbein on October 30th, 2008 at 7:59 pmAs we get set for the weekend, I’ll remind you the first trading day of the month has performed very well. Over the last 13 years, the S&P 500 is up 64.1%, but the combined return of the first trading day is up 68.6%. The first day of the month makes up slightly less than 5% of trading days.

-

-

Archives

- May 2025

- April 2025

- March 2025

- February 2025

- January 2025

- December 2024

- November 2024

- October 2024

- September 2024

- August 2024

- July 2024

- June 2024

- May 2024

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- July 2019

- June 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- May 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- July 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- March 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- July 2016

- June 2016

- May 2016

- April 2016

- March 2016

- February 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- July 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- April 2015

- March 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- December 2014

- November 2014

- October 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

- July 2014

- June 2014

- May 2014

- April 2014

- March 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- July 2013

- June 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- August 2012

- July 2012

- June 2012

- May 2012

- April 2012

- March 2012

- February 2012

- January 2012

- December 2011

- November 2011

- October 2011

- September 2011

- August 2011

- July 2011

- June 2011

- May 2011

- April 2011

- March 2011

- February 2011

- January 2011

- December 2010

- November 2010

- October 2010

- September 2010

- August 2010

- July 2010

- June 2010

- May 2010

- April 2010

- March 2010

- February 2010

- January 2010

- December 2009

- November 2009

- October 2009

- September 2009

- August 2009

- July 2009

- June 2009

- May 2009

- April 2009

- March 2009

- February 2009

- January 2009

- December 2008

- November 2008

- October 2008

- September 2008

- August 2008

- July 2008

- June 2008

- May 2008

- April 2008

- March 2008

- February 2008

- January 2008

- December 2007

- November 2007

- October 2007

- September 2007

- August 2007

- July 2007

- June 2007

- May 2007

- April 2007

- March 2007

- February 2007

- January 2007

- December 2006

- November 2006

- October 2006

- September 2006

- August 2006

- July 2006

- June 2006

- May 2006

- April 2006

- March 2006

- February 2006

- January 2006

- December 2005

- November 2005

- October 2005

- September 2005

- August 2005

- July 2005

Eddy Elfenbein is a Washington, DC-based speaker, portfolio manager and editor of the blog Crossing Wall Street. His

Eddy Elfenbein is a Washington, DC-based speaker, portfolio manager and editor of the blog Crossing Wall Street. His