-

How Many Times Do I Have to Say it?

Posted by Eddy Elfenbein on May 13th, 2008 at 2:02 pmThe WSJ does it again. Every time someone comments on political markets, they have to say that these markets “fail” because the a contract going for over $0.50 didn’t pan out.

John McCain’s presidential campaign is doomed — at least, if you still believe what political futures markets indicate.

At the Irish electronic exchange Intrade, on which people bet on election outcomes and other events, the futures market suggests Mr. McCain has a 38% chance of becoming the 44th president. In the Iowa Electronic Markets, set up at the University of Iowa, Mr. McCain’s Republican Party gets a 41% chance of winning the popular vote for the White House.No. No. No.

They’re NOT predictions markets, they’re odds-setting markets. That’s something quite different. A 38% chance of winning is not a doomed campaign. I think a baseball player who’s batting .380 would be doing pretty well.

Google IPO’d at $85, today it’s at $585. That’s a $500 miss. Did the market fail? No, they adapted to new information.

As I’ve said several times before, these market are really just for fun and should be seen as nothing more than that.

Still, I don’t understand how people can so often miss this basic fact about the political markets. The markets move with new information. It doesn’t mean that a favored outcome is correct or incorrect. That’s not what the markets are trying to do. They’re trying to analyze new information as quickly as possible. They usually, but not always, do a pretty good job. -

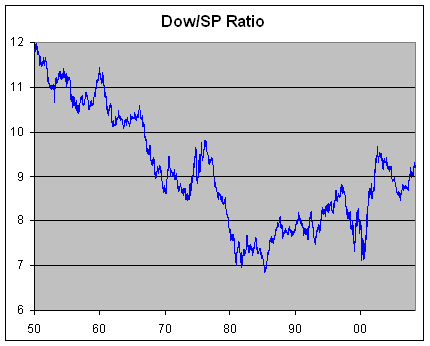

The Dow/S&P 500 Ratio

Posted by Eddy Elfenbein on May 13th, 2008 at 1:03 pmImagine if the Dow was 3,000 points higher than it is today. That’s where it would be if it had merely kept pace with the S&P 500 over the last few decades.

The Dow used to be about 10 or 11 times the S&P 500 (I’m referring to the index number, not market cap), but the ratio slowly sank for a long time.

The Dow/S&P 500 hit its low point in 1985 when the Dow was less than seven times the S&P. Since then, the Dow has had a bit of a comeback. In 2002, the ratio broke 9.5 for the first time in over 25 years.

After falling back some from 2002 to 2004, the Dow has outpaced the S&P 500 over the last two years.

-

Is Open Source Good for a Companies Stock?

Posted by Eddy Elfenbein on May 13th, 2008 at 11:02 amOliver Alexy looks at the impact of open source on a company’s shares:

But does giving ideas away help — or hurt — the company’s stock price? Will investors reward openness by driving up the company’s shares — or punish it by knocking the stock down?

Looking for News

To find out, I analyzed companies’ stock performance before and after they announced that they were making proprietary software open-source.

First, I searched through news releases from January 1999, shortly after the start of the open-source movement, to April 2007, looking for announcements that fit the bill. I then weeded out a number of companies, mostly because their announcements contained other news that might affect the stock price. That left 38 announcements from 30 companies.

Next, I analyzed the companies’ stock performance for 125 days prior to the announcement — to get a baseline for performance — and then watched the stock activity the day before the announcement and the day of the announcement. (I looked at the day before in case the markets had anticipated the news.)

Make It Clear

The results? Companies saw their stock price rise if they met one crucial condition: explaining how they expected their open strategy to bring in short-term revenue. Companies that clearly communicated a short-term revenue model saw an average stock-price increase of 1.6%. Companies that didn’t saw an average decline of 1.6%.That’s interesting though I’m a little uneasy about the robustness of that survey. It would be interesting to see if there could be more research done on a broader scale.

-

Guess What Stock Market Is at a New High?

Posted by Eddy Elfenbein on May 13th, 2008 at 1:08 amI’ll give you a hint.

Toronto.

Give up?Much of the momentum on the TSX has been caused by strength in resource stocks. The energy sector has climbed 40 per cent since January while the price for crude oil rose above US$125.

Investors have been turning to commodities stocks as a reliable investment alternative to international financial institutions, whose results have been bruised by the credit crisis.

“People were extremely nervous so they pulled in their horns, and they took their money out of risky investments,” said Bob Tebbutt, vice-president risk management at Peregrine Financial Group Canada.

“When people are nervous they automatically flock to things that are real — for example they flock to gold. It’s a risk place that they can put their money in and know that they’re theoretically going to get it back fairly easily.” -

Gazprom Meets Deep Purple

Posted by Eddy Elfenbein on May 12th, 2008 at 11:27 amThe New York Times has an article about the influence that Gazprom has on the Russian government. It’s not too much of a leap to say that Gazprom is the Russian government. The company’s president Dmitri Medvedev became Russia’s president last week. Putin, the former president, is now prime minister. And Viktor Zubkov, the former prime minister, will become the new head of Gazprom.

It’s hard to overemphasize Gazprom’s role in the Russian economy. It’s a sprawling company that raked in $91 billion last year; it employs 432,000 people, pays taxes equal to 20 percent of the Russian budget and has subsidiaries in industries as disparate as farming and aviation.

But I was most impressed to find that at the company’s 15th birthday party, they invited Medvedev’s band to play, Deep Purple.

“The gig at the Kremlin was fun, but it wasn’t wild,” Ian Gillan, Deep Purple’s frontman, wrote in an article for The Times of London after the show. “The young guys and more junior staff were all up on their feet, although they were looking nervously over at their bosses to see whether they could loosen their ties. It was as if they were asking, ‘How much fun are we allowed to have?’ ”

-

Get Over The Gap

Posted by Eddy Elfenbein on May 12th, 2008 at 10:31 amFrom IBD:

Trade Deficit: We have long been told that when the dollar “corrects,” making our goods cheaper abroad, the trade deficit will begin to fall sharply. Well, it’s finally happening. Now that it is, do you feel any better?

You shouldn’t. Because even though the trade gap narrowed by $3.5 billion, or 5.7%, to $58.2 billion in March from February, it was a sign of weakness rather than strength.

Compared with a year earlier, March exports rose 15.5% — a good thing, we suppose. But imports increased just 7.9%, a gain that would have been a lot lower if not for oil.

True enough, the deficit appears to be declining — after hitting repeated records in recent years. Exports are booming while import growth has slowed noticeably, due mainly to the slumping dollar.

On the surface, this looks like a good thing. After all, don’t we want to buy less from abroad and more from our own country? The answer is no if it means that the U.S. economy has slowed and is no longer pulling its weight in the world.

Journalists and pundits call the smaller deficit an “improvement,” or “good news.” It isn’t. We run a trade deficit not because we’re uncompetitive or others protect their markets, two great economic myths; we run deficits because we’re such an attractive place for investors from around the world to park their money. The deficit, in other words, is a sign of strength.

As any economist can tell you, the flip side of our trade deficit is our capital surplus, which measures foreign investment flows into and out of the U.S. When we run a trade deficit, by definition we must run a capital surplus — and vice versa.

Last year, for instance, we rang up a record $708.5 billion deficit for both goods and services. But we imported the equivalent of $738.6 billion in investment capital to offset that. This was used to buy Treasury notes, bonds and stocks, and to fund real estate, plants, equipment and worker training.

That foreign capital created jobs and added to our ability to consume. It may even have helped keep us out of recession.

So what does it say that our deficit is now shrinking?

On the whole, it means foreign investors find the U.S. economy a less inviting place to be, maybe because of the housing meltdown and concern over the upcoming election. But if the trend continues, it means we’re all going to have to consume less and save more to make up for the decline in foreign capital.

That might not be a bad thing, but don’t let anyone tell you it will be painless. In the short run, a falling trade deficit will boost GDP. Indeed, based on Friday’s data, it’s likely first-quarter GDP growth will be revised up from the first estimate of 0.6% to roughly 1.2%.

But in the long term, having less foreign investment means our economy will grow more slowly. That’s the downside.

Don’t believe it? Just look at Germany and Japan. They’ve run huge trade surpluses for years, yet their economies have grown slowly at best since at least 1990. They export lots of their capital, as all trade surplus nations do, so they have less to grow on. We import it — and grow faster.

As such, should we root for a smaller deficit? Well, a smaller trade deficit doesn’t have to be a negative. If it got smaller because Congress wised up and created private investment accounts for Social Security — which would raise the U.S. private savings rate — that might be a good thing.

But making the deficit smaller isn’t necessarily a laudable goal, since doing so often covers for other bad policies such as raising taxes, devaluing the dollar and reverting to protectionism.

All these things, by the way, have been proposed as “remedies” for the trade deficit, mostly by wrongheaded Democratic candidates and talk-show hosts. What they’d do, in fact, is shrink the deficit by shrinking the U.S. economy. We’d rather keep the deficits. -

Schwarzman’s Subprime Analogy

Posted by Eddy Elfenbein on May 10th, 2008 at 1:23 pm[It’s like] being a noodle salesman in Nagasaki when they dropped the A-bomb – not a lot of noodles left, and not a lot of people either.

My prediction: This will not end well.

-

Nicholas Financial’s Earnings

Posted by Eddy Elfenbein on May 9th, 2008 at 3:09 pmYesterday, Nicholas Financial (NICK) reported quarterly earnings of 20 cents a share. That’s for the company’s fourth quarter which ended on March 31. For the same quarter one year before, NICK earned 29 cents a share. Revenue dropped 6% to $12.7 million.

Yes, I still think this is an absurdly undervalued stock. For the entire fiscal year, NICK earned 94 cents a share. That still means the company is going for about seven times earnings. Nicholas Financial has now reported revenue increases for 18 straight years. -

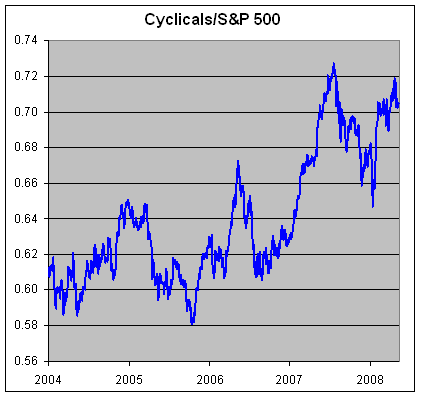

The Cyclicals are Still Overpriced

Posted by Eddy Elfenbein on May 7th, 2008 at 12:38 pmHere’s a look at something I wrote a lot about last year, it’s the ratio of the Morgan Stanley Cyclical Index (^CYC) to the S&P 500 (^GSPC):

The ratio peaked on July 19 and started falling for the next few months. It eventually reached a bottom on January 9 and has been steadily climbing ever since. -

Signs of Health in the Credit Markets

Posted by Eddy Elfenbein on May 7th, 2008 at 10:42 amIn the course of a three-and-a-half- hour dinner at Manhattan’s Smith & Wollensky steakhouse, Emil Assentato went from also-ran to the top of the world’s fastest-growing credit market.

By the end of the meal, Assentato, 58, the head of Cie. Financiere Tradition’s North American securities business who races cars on weekends, had persuaded more than a dozen credit- derivatives brokers led by Donald Fewer and Michael Babcock to defect from rival GFI Group Inc., court documents allege. In the end, 21 would leave for Tradition with the promise of $130 million over three to five years, about $6 million apiece.

Tradition’s attack did more than decimate GFI’s credit- default swap desk. It also raised the bar for the “extraordinary” pay commanded by derivatives brokers who match buyers and sellers between banks, according to affidavits filed by New York-based GFI in a suit against Tradition. As Wall Street buckles under the biggest credit-market losses in history, brokerage firms are seeking to tap the $10 billion of fees generated by middlemen, who spend as much as $500 million a year entertaining traders with strippers, football games and evenings at trendy Manhattan bars, based on court records and interviews with industry officials.

-

-

Archives

- June 2025

- May 2025

- April 2025

- March 2025

- February 2025

- January 2025

- December 2024

- November 2024

- October 2024

- September 2024

- August 2024

- July 2024

- June 2024

- May 2024

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- July 2019

- June 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- May 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- July 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- March 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- July 2016

- June 2016

- May 2016

- April 2016

- March 2016

- February 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- July 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- April 2015

- March 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- December 2014

- November 2014

- October 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

- July 2014

- June 2014

- May 2014

- April 2014

- March 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- July 2013

- June 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- August 2012

- July 2012

- June 2012

- May 2012

- April 2012

- March 2012

- February 2012

- January 2012

- December 2011

- November 2011

- October 2011

- September 2011

- August 2011

- July 2011

- June 2011

- May 2011

- April 2011

- March 2011

- February 2011

- January 2011

- December 2010

- November 2010

- October 2010

- September 2010

- August 2010

- July 2010

- June 2010

- May 2010

- April 2010

- March 2010

- February 2010

- January 2010

- December 2009

- November 2009

- October 2009

- September 2009

- August 2009

- July 2009

- June 2009

- May 2009

- April 2009

- March 2009

- February 2009

- January 2009

- December 2008

- November 2008

- October 2008

- September 2008

- August 2008

- July 2008

- June 2008

- May 2008

- April 2008

- March 2008

- February 2008

- January 2008

- December 2007

- November 2007

- October 2007

- September 2007

- August 2007

- July 2007

- June 2007

- May 2007

- April 2007

- March 2007

- February 2007

- January 2007

- December 2006

- November 2006

- October 2006

- September 2006

- August 2006

- July 2006

- June 2006

- May 2006

- April 2006

- March 2006

- February 2006

- January 2006

- December 2005

- November 2005

- October 2005

- September 2005

- August 2005

- July 2005

Eddy Elfenbein is a Washington, DC-based speaker, portfolio manager and editor of the blog Crossing Wall Street. His

Eddy Elfenbein is a Washington, DC-based speaker, portfolio manager and editor of the blog Crossing Wall Street. His