-

Wall Street and the Family Feud

Posted by Eddy Elfenbein on August 24th, 2007 at 10:05 am

From the Web site, the worst Family Feud Answers:Question: Name the worst kind of shoe to run a marathon in.

#1 Answer: High heels

Worst Answer: Scuba flippers

Louie Anderson’s Response: If it’s up there… I’ll be surprised.There’s something fascinating about the game show the Family Feud. You don’t have to give the best answer, or the funniest answer. You don’t even need to give a correct answer. All you need to do is give the answer everyone else gives. The show rewards people for being exactly like the largest amount of other people. Anything exceptional is not only discouraged, it’s actively punished.

I couldn’t help but think of the show as I read this WSJ article on why so many quant funds are having trouble:A number of quant funds, which use statistical models to find winning trading strategies, reported heavy losses this month. In many cases, the managers pointed their fingers at other quantitative hedge funds, essentially saying they all owned many of the same stocks and their models told them all to sell at the same time, driving down the share prices, hurting everyone in the process.

In a letter to investors, Jim Simons of the hedge fund Renaissance Technologies wrote the quantitative funds behind the selling “undoubtedly share some signals in common with our own, and the result has been losses.” It didn’t help that quant funds are among the fastest expanding categories of hedge funds.In other words, a lot of folks are running down Wall Street in scuba slippers.

Filings with the Securities and Exchange Commission show that as of the end of June, quantitative hedge funds often shared large positions in the same stocks. Renaissance held 1.1% of the shares outstanding of NVR Inc., a Virginia construction and home-building company. AQR Capital Management, another quant fund, held 0.9% of the company’s shares and quant fund Numeric Investors had a 1.6% stake.

NVR stock, which closed yesterday at $571 a share, trades less than most companies of its size. The shares have bounced higher since the selloff, but they are off 8.4% over the past month.

The overlap in quant funds’ positions wasn’t limited to NVR. Satya Pradhuman, director of research at Cirrus Research, which analyzes small and midsize stocks, found 148 other companies with market capitalizations between $2 billion and $10 billion where large quant funds owned 5% or more of the shares outstanding.

As a whole, those companies’ shares underperformed the shares of other midcap stocks during the selloff. Mr. Pradhuman found 473 small-cap stocks, with market capitalizations of $250 million to $2 billion, where the quant funds owned 5% or more of the shares outstanding. These stocks also performed worse than other similar stocks.

The midcap companies where quant funds held big stakes included packaging company Pactiv Corp., toy maker Hasbro Inc. and managed care provider WellCare Health Plans Inc. Small caps included printer Deluxe Corp., consumer-products company Russ Berrie & Co. and health-care equipment maker Zoll Medical Corp.The Life of Brian:

Brian: Please, please, please listen! I’ve got one or two things to say.

The Crowd: Tell us! Tell us both of them!

Brian: Look, you’ve got it all wrong! You don’t NEED to follow ME, You don’t NEED to follow ANYBODY! You’ve got to think for your selves! You’re ALL individuals!

The Crowd: Yes! We’re all individuals!

Brian: You’re all different!

The Crowd: Yes, we ARE all different!

Man in crowd: I’m not… -

Intangible Wealth

Posted by Eddy Elfenbein on August 24th, 2007 at 9:49 amReason has a fascinating interview with Kirk Hamilton on what really makes a country wealthy, its intangible wealth. This is from the intro:

Oil, soil, copper, and forests are forms of wealth. So are factories, houses, and roads. But according to a 2005 study by the World Bank, such solid goods amount to only about 20 percent of the wealth of rich nations and 40 percent of the wealth of poor countries.

So what accounts for the majority? World Bank environmental economist Kirk Hamilton and his team in the bank’s environment department have found that most of humanity’s wealth isn’t made of physical stuff. It is intangible. In their extraordinary but vastly underappreciated report, Where Is The Wealth Of Nations?: Measuring Capital for the 21st Century, Hamilton’s team found that “human capital and the value of institutions (as measured by rule of law) constitute the largest share of wealth in virtually all countries.” -

Not a Good Day for Pro Athletes’ Investments

Posted by Eddy Elfenbein on August 23rd, 2007 at 3:02 pmFirst, we learn that Joe Montana’s hedge fund was down 12% in August.

Now, we hear that Latrell Sprewell had his 70-foot yacht seized. Apparently, he’s behind on his mortgage payments. -

Spiers 2, Portfolio 0

Posted by Eddy Elfenbein on August 23rd, 2007 at 2:58 pmElizabeth Spiers takes a look at the second issue of Portfolio, and she’s not impressed (via DealBreaker):

The second issue of Condé Nast’s big-budget business mag, Portfolio, arrived on newsstands last week and I plucked one from atop an enormous stack of them at the Union Square Barnes & Noble in New York. Between the weeks of media coverage citing long weekends, staff disagreements, reports of fewer ad pages in the second issue and more recently, the public firing of deputy editor Jim Impoco, the magazine has created enough internal melodrama to stoke curiosity–mine, anyway–about how well the second effort stacks up to the first. The temptation to speculate about the skyscraper stack of Portfolios being indicative of oversupply (the money and resources the company is pouring into the publication) or lack of demand (the target audience isn’t interested in reading it) lingers, but one retail outlet isn’t a legitimate sample size.

And neither is one reader. But if Portfolio were a high-end business magazine, I’d be an enthusiastic subscriber. The problem is that it’s not. Press coverage has referred to it as a “Vanity Fair for business.” It’s not that, either.

The unfortunate thing is that it could be both. Portfolio should be a magazine about power, specifically in the private sector: who has it, how they got it, what they do with it, and whether they’re using it for good or evil. (If you’re going to write about Cerberus, for example, I have less interest in how secretive Steve Feinberg claims the firm is than what sort of deals John Snow is cutting in China, with whom, and to what extent the Chinese government is involved–something that has wider-ranging implications than the notion that some hedge-fund managers play against stereotypes and drive pickup trucks.) The magazine should exploit the biggest major advantage that print has over the web and that monthlies can generally do better than weeklies–long-form narrative journalism. There are huge swaths of the private sector that aren’t materially covered right now. These are stories that existing mass-market business publications mostly bypass: They tend to cover large public companies; which are most relevant to the average investor. But that’s a very narrow view of the business world. It’s fine for The Wall Street Journal, which purposefully and usefully focuses on investors, but limiting for a general-interest business magazine.

That Portfolio hasn’t taken advantage of its opportunity is probably a reflection of editor-in-chief Joanne Lipman’s background, which most famously consists of launching The Wall Street Journal’s “Weekend Journal,” a lifestyle-oriented section that had little to do with covering hard business stories. And Portfolio’s flaws seem to be rooted in its editor’s entrenched habits from doing a very different sort of journalism. -

45 Years Ago Today

Posted by Eddy Elfenbein on August 22nd, 2007 at 4:31 pm -

Wednesday Again

Posted by Eddy Elfenbein on August 22nd, 2007 at 4:02 pmFor the 21st time in the last 30 Wednesdays, the S&P 500 closed higher. This is also the 56th up Wednesday in the last 81.

-

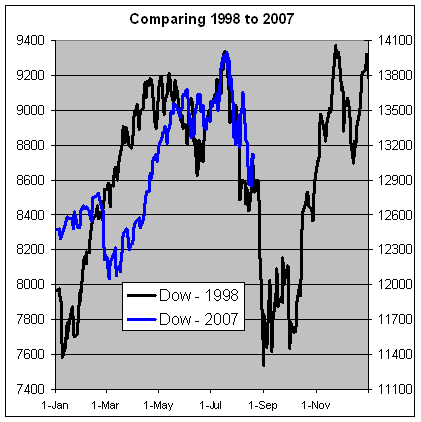

Comparing 1998 and 2007

Posted by Eddy Elfenbein on August 22nd, 2007 at 3:11 pmThis chart has been making the rounds and it’s supposed to be telling us EXACTLY WHAT’S GOING TO HAPPEN!!!

Honestly, I don’t see it but I’ll let you be the judge.

The Dow from 1998 is the black line and the left scale; 2007 is the blue line and the right scale.

-

FactSet Research Systems

Posted by Eddy Elfenbein on August 22nd, 2007 at 12:36 pmFactSet Research Systems (FDS) is a company whose products most professional money manager are familiar with, but it’s the stock that’s been catching my eye lately.

The story here is pretty simple: Wall Street is addicted to data and FDS is their dealer. The fundamentals are solid; fat margins, zero debt and nice history of churning out 20% EPS increases. I’ll warn you, FDS is expensive although it recently got a little less expense. The shares are off about 20% from their high. I think the market is concerned that many of FDS’ clients are these dearly departed hedge funds. I doubt that’s the case. FDS has a large diversified client base (2,000 clients and 33,000 users). This is a well-entrenched business. -

The Financial Times: Don’t Cut

Posted by Eddy Elfenbein on August 22nd, 2007 at 10:26 amNot everyone is on the rate-cut bandwagon. The Financial Times opines against one:

Credit fuels the modern economy, and if the dislocation in the money markets lasts another month or two, investment, consumption and growth in the real economy will suffer. Central banks must restore confidence, but rather than cut interest rates they should extend liquidity operations to longer maturities, more collateral and possibly even different counterparties.

Liquidity injections by the Federal Reserve and European Central Bank have brought down overnight interest rates, but longer-term borrowing is still unusually expensive, while US Treasury bills have been trading at panic levels of below 3 per cent. It is hard to borrow using collateral not issued or guaranteed by a government. Central bank intervention has not worked so far.

This is not a recession panic, as in 1998, when the Long-Term Capital Management crisis coincided with weak economic data.

Nor is it a panic caused by serious credit losses. Defaults on US subprime mortgages are miles off a level at which triple-A bonds backed by them would suffer losses. When they do trade, the prices can be reasonable: as part of its acquisition by Kaupthing last week, the Dutch bank NIBC sold its subprime portfolio for 78 cents on the dollar.

The problem is that the bonds do not trade – the crisis is one of liquidity – and that has spread to short-term debt sold by investment vehicles that may be exposed.

The futures market expects the Fed to cut interest rates aggressively, but unless the Fed expects harm to the real economy, that policy makes little sense. It is indiscriminate and so creates moral hazard in the markets, but there is also a good chance it would not work.

The Fed has already pushed its main funds rate down well below its 5.25 per cent target, but the problem is not overnight liquidity at banks, it is perceived credit risk on three-month commercial paper. Giving cheaper money to banks might or might not change that perception.

The lenders of last resort need to find ways to get money through the traditional banking system to the markets where the trouble is. They can do so by agreeing to lend against more securities (the Bank of Canada is already accepting commercial paper); by lending for a few months rather than overnight; and possibly by dealing with off-balance-sheet vehicles directly.

There should be no handouts – lending should be at penalty interest rates – but what is needed to jump-start the credit markets is more targeted liquidity. Central banks should not crack and cut their policy rates while they have more suitable tools in the box. -

Fed: Cautiously Optimistic!

Posted by Eddy Elfenbein on August 22nd, 2007 at 10:20 amGreat news! The WSJ reports:

Federal Reserve officials are cautiously optimistic that the series of steps they have taken to stabilize markets have started to work.

Ugh! “Cautiously optimistic” is one of the great all-purpose bullshit media phrases of all-time. It means nothing. It sounds thoughtful and sober, but it really communicates nothing. You can see why central bankers love using it.

Neil Westergaard nailed the phrase a few years ago:What a great all-purpose, meaningless qualifier to keep from looking stupid. It’s much better than just saying “I don’t know.” It implies that that the person really does know something important, but is being conservative and careful in the distribution of information, holding back the unverifiable facts for the good of the republic.

Or covering their behinds.

“Cautiously optimistic.” If the economy goes into the dumper again, we can say our earlier caution was warranted. If things pick up, we were right to be optimistic and “knew it all along.”The Journal continues:

Officials acknowledge conditions are far from calm, and markets could easily take a turn for the worse. But they cite stable stock prices, a pickup in issuance of jumbo mortgages and other factors as evidence that in recent days conditions have improved, though gradually, instead of worsened.

Many on Wall Street are more pessimistic, and believe the Fed will still have to cut interest rates sharply, perhaps starting in the next week or two. But as long as Fed officials think things are getting better, they are less likely to feel pressured to cut interest rates immediately and more likely to wait until their scheduled meeting Sept. 18 to decide.Going by the futures market, I’d say the Federal Reserve will cut in September and again in October. I don’t think the Fed wants to break out of its pattern of only cutting rates at meetings. It could, but I don’t think it sees the current situation as being that drastic.

One of my long-standing criticisms of mainstream market analysis is the centrality placed on the Federal Reserve. This is classic over-agency bias. Sure, the Fed is important, but it’s not that important. The Fed really can’t fight what the market wants. If the market demands a rate cut, well…sooner or later, it will get one.

Another issue that I’ve noticed is that some observers are treating the market’s recent activity as some major come-uppance for speculators. The market’s decline is not very steep and the most severe pain is confined to a small number of stocks. Yet, people will use any decline as an excuse for public moralizing.

Let’s keep in mind that equity valuations are still quite modest. Also, growth stocks have outperformed value stocks since the market broke. That’s hardly a come-uppance to irrational exuberance. Viewed from the long-term, this summer is barely a hiccup.

I still think the risk/reward tradeoff greatly favors equity investors. You could even say that I’m cautiously optimistic.

-

-

Archives

- May 2025

- April 2025

- March 2025

- February 2025

- January 2025

- December 2024

- November 2024

- October 2024

- September 2024

- August 2024

- July 2024

- June 2024

- May 2024

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- July 2019

- June 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- May 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- July 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- March 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- July 2016

- June 2016

- May 2016

- April 2016

- March 2016

- February 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- July 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- April 2015

- March 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- December 2014

- November 2014

- October 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

- July 2014

- June 2014

- May 2014

- April 2014

- March 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- July 2013

- June 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- August 2012

- July 2012

- June 2012

- May 2012

- April 2012

- March 2012

- February 2012

- January 2012

- December 2011

- November 2011

- October 2011

- September 2011

- August 2011

- July 2011

- June 2011

- May 2011

- April 2011

- March 2011

- February 2011

- January 2011

- December 2010

- November 2010

- October 2010

- September 2010

- August 2010

- July 2010

- June 2010

- May 2010

- April 2010

- March 2010

- February 2010

- January 2010

- December 2009

- November 2009

- October 2009

- September 2009

- August 2009

- July 2009

- June 2009

- May 2009

- April 2009

- March 2009

- February 2009

- January 2009

- December 2008

- November 2008

- October 2008

- September 2008

- August 2008

- July 2008

- June 2008

- May 2008

- April 2008

- March 2008

- February 2008

- January 2008

- December 2007

- November 2007

- October 2007

- September 2007

- August 2007

- July 2007

- June 2007

- May 2007

- April 2007

- March 2007

- February 2007

- January 2007

- December 2006

- November 2006

- October 2006

- September 2006

- August 2006

- July 2006

- June 2006

- May 2006

- April 2006

- March 2006

- February 2006

- January 2006

- December 2005

- November 2005

- October 2005

- September 2005

- August 2005

- July 2005

Eddy Elfenbein is a Washington, DC-based speaker, portfolio manager and editor of the blog Crossing Wall Street. His

Eddy Elfenbein is a Washington, DC-based speaker, portfolio manager and editor of the blog Crossing Wall Street. His