-

Text of Bernanke’s Speech

Posted by Eddy Elfenbein on October 1st, 2012 at 12:35 pmChairman Ben S. Bernanke

At the Economic Club of Indiana, Indianapolis, Indiana

October 1, 2012

Five Questions about the Federal Reserve and Monetary PolicyGood afternoon. I am pleased to be able to join the Economic Club of Indiana for lunch today. I note that the mission of the club is “to promote an interest in, and enlighten its membership on, important governmental, economic and social issues.” I hope my remarks today will meet that standard. Before diving in, I’d like to thank my former colleague at the White House, Al Hubbard, for helping to make this event possible. As the head of the National Economic Council under President Bush, Al had the difficult task of making sure that diverse perspectives on economic policy issues were given a fair hearing before recommendations went to the President. Al had to be a combination of economist, political guru, diplomat, and traffic cop, and he handled it with great skill.

My topic today is “Five Questions about the Federal Reserve and Monetary Policy.” I have used a question-and-answer format in talks before, and I know from much experience that people are eager to know more about the Federal Reserve, what we do, and why we do it. And that interest is even broader than one might think. I’m a baseball fan, and I was excited to be invited to a recent batting practice of the playoff-bound Washington Nationals. I was introduced to one of the team’s star players, but before I could press my questions on some fine points of baseball strategy, he asked, “So, what’s the scoop on quantitative easing?” So, for that player, for club members and guests here today, and for anyone else curious about the Federal Reserve and monetary policy, I will ask and answer these five questions:

1. What are the Fed’s objectives, and how is it trying to meet them?

2. What’s the relationship between the Fed’s monetary policy and the fiscal decisions of the Administration and the Congress?

3. What is the risk that the Fed’s accommodative monetary policy will lead to inflation?

4. How does the Fed’s monetary policy affect savers and investors?

5. How is the Federal Reserve held accountable in our democratic society?What Are the Fed’s Objectives, and How Is It Trying to Meet Them?

The first question on my list concerns the Federal Reserve’s objectives and the tools it has to try to meet them.As the nation’s central bank, the Federal Reserve is charged with promoting a healthy economy–broadly speaking, an economy with low unemployment, low and stable inflation, and a financial system that meets the economy’s needs for credit and other services and that is not itself a source of instability. We pursue these goals through a variety of means. Together with other federal supervisory agencies, we oversee banks and other financial institutions. We monitor the financial system as a whole for possible risks to its stability. We encourage financial and economic literacy, promote equal access to credit, and advance local economic development by working with communities, nonprofit organizations, and others around the country. We also provide some basic services to the financial sector–for example, by processing payments and distributing currency and coin to banks.

But today I want to focus on a role that is particularly identified with the Federal Reserve–the making of monetary policy. The goals of monetary policy–maximum employment and price stability–are given to us by the Congress. These goals mean, basically, that we would like to see as many Americans as possible who want jobs to have jobs, and that we aim to keep the rate of increase in consumer prices low and stable.

In normal circumstances, the Federal Reserve implements monetary policy through its influence on short-term interest rates, which in turn affect other interest rates and asset prices.1 Generally, if economic weakness is the primary concern, the Fed acts to reduce interest rates, which supports the economy by inducing businesses to invest more in new capital goods and by leading households to spend more on houses, autos, and other goods and services. Likewise, if the economy is overheating, the Fed can raise interest rates to help cool total demand and constrain inflationary pressures.

Following this standard approach, the Fed cut short-term interest rates rapidly during the financial crisis, reducing them to nearly zero by the end of 2008–a time when the economy was contracting sharply. At that point, however, we faced a real challenge: Once at zero, the short-term interest rate could not be cut further, so our traditional policy tool for dealing with economic weakness was no longer available. Yet, with unemployment soaring, the economy and job market clearly needed more support. Central banks around the world found themselves in a similar predicament. We asked ourselves, “What do we do now?”

To answer this question, we could draw on the experience of Japan, where short-term interest rates have been near zero for many years, as well as a good deal of academic work. Unable to reduce short-term interest rates further, we looked instead for ways to influence longer-term interest rates, which remained well above zero. We reasoned that, as with traditional monetary policy, bringing down longer-term rates should support economic growth and employment by lowering the cost of borrowing to buy homes and cars or to finance capital investments. Since 2008, we’ve used two types of less-traditional monetary policy tools to bring down longer-term rates.

The first of these less-traditional tools involves the Fed purchasing longer-term securities on the open market–principally Treasury securities and mortgage-backed securities guaranteed by government-sponsored enterprises such as Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. The Fed’s purchases reduce the amount of longer-term securities held by investors and put downward pressure on the interest rates on those securities. That downward pressure transmits to a wide range of interest rates that individuals and businesses pay. For example, when the Fed first announced purchases of mortgage-backed securities in late 2008, 30-year mortgage interest rates averaged a little above 6percent; today they average about 3-1/2 percent. Lower mortgage rates are one reason for the improvement we have been seeing in the housing market, which in turn is benefiting the economy more broadly. Other important interest rates, such as corporate bond rates and rates on auto loans, have also come down. Lower interest rates also put upward pressure on the prices of assets, such as stocks and homes, providing further impetus to household and business spending.

The second monetary policy tool we have been using involves communicating our expectations for how long the short-term interest rate will remain exceptionally low. Because the yield on, say, a five-year security embeds market expectations for the course of short-term rates over the next five years, convincing investors that we will keep the short-term rate low for a longer time can help to pull down market-determined longer-term rates. In sum, the Fed’s basic strategy for strengthening the economy–reducing interest rates and easing financial conditions more generally–is the same as it has always been. The difference is that, with the short-term interest rate nearly at zero, we have shifted to tools aimed at reducing longer-term interest rates more directly.

Last month, my colleagues and I used both tools–securities purchases and communications about our future actions–in a coordinated way to further support the recovery and the job market. Why did we act? Though the economy has been growing since mid-2009 and we expect it to continue to expand, it simply has not been growing fast enough recently to make significant progress in bringing down unemployment. At 8.1 percent, the unemployment rate is nearly unchanged since the beginning of the year and is well above normal levels. While unemployment has been stubbornly high, our economy has enjoyed broad price stability for some time, and we expect inflation to remain low for the foreseeable future. So the case seemed clear to most of my colleagues that we could do more to assist economic growth and the job market without compromising our goal of price stability.

Specifically, what did we do? On securities purchases, we announced that we would buy mortgage-backed securities guaranteed by the government-sponsored enterprises at a rate of $40 billion per month. Those purchases, along with the continuation of a previous program involving Treasury securities, mean we are buying $85 billion of longer-term securities per month through the end of the year. We expect these purchases to put further downward pressure on longer-term interest rates, including mortgage rates. To underline the Federal Reserve’s commitment to fostering a sustainable economic recovery, we said that we would continue securities purchases and employ other policy tools until the outlook for the job market improves substantially in a context of price stability.

In the category of communications policy, we also extended our estimate of how long we expect to keep the short-term interest rate at exceptionally low levels to at least mid-2015. That doesn’t mean that we expect the economy to be weak through 2015. Rather, our message was that, so long as price stability is preserved, we will take care not to raise rates prematurely. Specifically, we expect that a highly accommodative stance of monetary policy will remain appropriate for a considerable time after the economy strengthens. We hope that, by clarifying our expectations about future policy, we can provide individuals, families, businesses, and financial markets greater confidence about the Federal Reserve’s commitment to promoting a sustainable recovery and that, as a result, they will become more willing to invest, hire and spend.

Now, as I have said many times, monetary policy is no panacea. It can be used to support stronger economic growth in situations in which, as today, the economy is not making full use of its resources, and it can foster a healthier economy in the longer term by maintaining low and stable inflation. However, many other steps could be taken to strengthen our economy over time, such as putting the federal budget on a sustainable path, reforming the tax code, improving our educational system, supporting technological innovation, and expanding international trade. Although monetary policy cannot cure the economy’s ills, particularly in today’s challenging circumstances, we do think it can provide meaningful help. So we at the Federal Reserve are going to do what we can do and trust that others, in both the public and private sectors, will do what they can as well.

What’s the Relationship between Monetary Policy and Fiscal Policy?

That brings me to the second question: What’s the relationship between monetary policy and fiscal policy? To answer this question, it may help to begin with the more basic question of how monetary and fiscal policy differ.In short, monetary policy and fiscal policy involve quite different sets of actors, decisions, and tools. Fiscal policy involves decisions about how much the government should spend, how much it should tax, and how much it should borrow. At the federal level, those decisions are made by the Administration and the Congress. Fiscal policy determines the size of the federal budget deficit, which is the difference between federal spending and revenues in a year. Borrowing to finance budget deficits increases the government’s total outstanding debt.

As I have discussed, monetary policy is the responsibility of the Federal Reserve–or, more specifically, the Federal Open Market Committee, which includes members of the Federal Reserve’s Board of Governors and presidents of Federal Reserve Banks. Unlike fiscal policy, monetary policy does not involve any taxation, transfer payments, or purchases of goods and services. Instead, as I mentioned, monetary policy mainly involves the purchase and sale of securities. The securities that the Fed purchases in the conduct of monetary policy are held in our portfolio and earn interest. The great bulk of these interest earnings is sent to the Treasury, thereby helping reduce the government deficit. In the past three years, the Fed remitted $200 billion to the federal government. Ultimately, the securities held by the Fed will mature or will be sold back into the market. So the odds are high that the purchase programs that the Fed has undertaken in support of the recovery will end up reducing, not increasing, the federal debt, both through the interest earnings we send the Treasury and because a stronger economy tends to lead to higher tax revenues and reduced government spending (on unemployment benefits, for example).

Even though our activities are likely to result in a lower national debt over the long term, I sometimes hear the complaint that the Federal Reserve is enabling bad fiscal policy by keeping interest rates very low and thereby making it cheaper for the federal government to borrow. I find this argument unpersuasive. The responsibility for fiscal policy lies squarely with the Administration and the Congress. At the Federal Reserve, we implement policy to promote maximum employment and price stability, as the law under which we operate requires. Using monetary policy to try to influence the political debate on the budget would be highly inappropriate. For what it’s worth, I think the strategy would also likely be ineffective: Suppose, notwithstanding our legal mandate, the Federal Reserve were to raise interest rates for the purpose of making it more expensive for the government to borrow. Such an action would substantially increase the deficit, not only because of higher interest rates, but also because the weaker recovery that would result from premature monetary tightening would further widen the gap between spending and revenues. Would such a step lead to better fiscal outcomes? It seems likely that a significant widening of the deficit–which would make the needed fiscal actions even more difficult and painful–would worsen rather than improve the prospects for a comprehensive fiscal solution.

I certainly don’t underestimate the challenges that fiscal policymakers face. They must find ways to put the federal budget on a sustainable path, but not so abruptly as to endanger the economic recovery in the near term. In particular, the Congress and the Administration will soon have to address the so-called fiscal cliff, a combination of sharply higher taxes and reduced spending that is set to happen at the beginning of the year. According to the Congressional Budget Office and virtually all other experts, if that were allowed to occur, it would likely throw the economy back into recession. The Congress and the Administration will also have to raise the debt ceiling to prevent the Treasury from defaulting on its obligations, an outcome that would have extremely negative consequences for the country for years to come. Achieving these fiscal goals would be even more difficult if monetary policy were not helping support the economic recovery.

What Is the Risk that the Federal Reserve’s Monetary Policy Will Lead to Inflation?

A third question, and an important one, is whether the Federal Reserve’s monetary policy will lead to higher inflation down the road. In response, I will start by pointing out that the Federal Reserve’s price stability record is excellent, and we are fully committed to maintaining it. Inflation has averaged close to 2 percent per year for several decades, and that’s about where it is today. In particular, the low interest rate policies the Fed has been following for about five years now have not led to increased inflation. Moreover, according to a variety of measures, the public’s expectations of inflation over the long run remain quite stable within the range that they have been for many years.With monetary policy being so accommodative now, though, it is not unreasonable to ask whether we are sowing the seeds of future inflation. A related question I sometimes hear–which bears also on the relationship between monetary and fiscal policy, is this: By buying securities, are you “monetizing the debt”–printing money for the government to use–and will that inevitably lead to higher inflation? No, that’s not what is happening, and that will not happen. Monetizing the debt means using money creation as a permanent source of financing for government spending. In contrast, we are acquiring Treasury securities on the open market and only on a temporary basis, with the goal of supporting the economic recovery through lower interest rates. At the appropriate time, the Federal Reserve will gradually sell these securities or let them mature, as needed, to return its balance sheet to a more normal size. Moreover, the way the Fed finances its securities purchases is by creating reserves in the banking system. Increased bank reserves held at the Fed don’t necessarily translate into more money or cash in circulation, and, indeed, broad measures of the supply of money have not grown especially quickly, on balance, over the past few years.

For controlling inflation, the key question is whether the Federal Reserve has the policy tools to tighten monetary conditions at the appropriate time so as to prevent the emergence of inflationary pressures down the road. I’m confident that we have the necessary tools to withdraw policy accommodation when needed, and that we can do so in a way that allows us to shrink our balance sheet in a deliberate and orderly way. For example, the Fed can tighten policy, even if our balance sheet remains large, by increasing the interest rate we pay banks on reserve balances they deposit at the Fed. Because banks will not lend at rates lower than what they can earn at the Fed, such an action should serve to raise rates and tighten credit conditions more generally, preventing any tendency toward overheating in the economy.

Of course, having effective tools is one thing; using them in a timely way, neither too early nor too late, is another. Determining precisely the right time to “take away the punch bowl” is always a challenge for central bankers, but that is true whether they are using traditional or nontraditional policy tools. I can assure you that my colleagues and I will carefully consider how best to foster both of our mandated objectives, maximum employment and price stability, when the time comes to make these decisions.

How Does the Fed’s Monetary Policy Affect Savers and Investors?

The concern about possible inflation is a concern about the future. One concern in the here and now is about the effect of low interest rates on savers and investors. My colleagues and I know that people who rely on investments that pay a fixed interest rate, such as certificates of deposit, are receiving very low returns, a situation that has involved significant hardship for some.However, I would encourage you to remember that the current low levels of interest rates, while in the first instance a reflection of the Federal Reserve’s monetary policy, are in a larger sense the result of the recent financial crisis, the worst shock to this nation’s financial system since the 1930s. Interest rates are low throughout the developed world, except in countries experiencing fiscal crises, as central banks and other policymakers try to cope with continuing financial strains and weak economic conditions.

A second observation is that savers often wear many economic hats. Many savers are also homeowners; indeed, a family’s home may be its most important financial asset. Many savers are working, or would like to be. Some savers own businesses, and–through pension funds and 401(k) accounts–they often own stocks and other assets. The crisis and recession have led to very low interest rates, it is true, but these events have also destroyed jobs, hamstrung economic growth, and led to sharp declines in the values of many homes and businesses. What can be done to address all of these concerns simultaneously? The best and most comprehensive solution is to find ways to a stronger economy. Only a strong economy can create higher asset values and sustainably good returns for savers. And only a strong economy will allow people who need jobs to find them. Without a job, it is difficult to save for retirement or to buy a home or to pay for an education, irrespective of the current level of interest rates.

The way for the Fed to support a return to a strong economy is by maintaining monetary accommodation, which requires low interest rates for a time. If, in contrast, the Fed were to raise rates now, before the economic recovery is fully entrenched, house prices might resume declines, the values of businesses large and small would drop, and, critically, unemployment would likely start to rise again. Such outcomes would ultimately not be good for savers or anyone else.

How Is the Federal Reserve Held Accountable in a Democratic Society?

I will turn, finally, to the question of how the Federal Reserve is held accountable in a democratic society.The Federal Reserve was created by the Congress, now almost a century ago. In the Federal Reserve Act and subsequent legislation, the Congress laid out the central bank’s goals and powers, and the Fed is responsible to the Congress for meeting its mandated objectives, including fostering maximum employment and price stability. At the same time, the Congress wisely designed the Federal Reserve to be insulated from short-term political pressures. For example, members of the Federal Reserve Board are appointed to staggered, 14-year terms, with the result that some members may serve through several Administrations. Research and practical experience have established that freeing the central bank from short-term political pressures leads to better monetary policy because it allows policymakers to focus on what is best for the economy in the longer run, independently of near-term electoral or partisan concerns. All of the members of the Federal Open Market Committee take this principle very seriously and strive always to make monetary policy decisions based solely on factual evidence and careful analysis.

It is important to keep politics out of monetary policy decisions, but it is equally important, in a democracy, for those decisions–and, indeed, all of the Federal Reserve’s decisions and actions–to be undertaken in a strong framework of accountability and transparency. The American people have a right to know how the Federal Reserve is carrying out its responsibilities and how we are using taxpayer resources.

One of my principal objectives as Chairman has been to make monetary policy at the Federal Reserve as transparent as possible. We promote policy transparency in many ways. For example, the Federal Open Market Committee explains the reasons for its policy decisions in a statement released after each regularly scheduled meeting, and three weeks later we publish minutes with a detailed summary of the meeting discussion. The Committee also publishes quarterly economic projections with information about where we anticipate both policy and the economy will be headed over the next several years. I hold news conferences four times a year and testify often before congressional committees, including twice-yearly appearances that are specifically designated for the purpose of my presenting a comprehensive monetary policy report to the Congress. My colleagues and I frequently deliver speeches, such as this one, in towns and cities across the country.

The Federal Reserve is also very open about its finances and operations. The Federal Reserve Act requires the Federal Reserve to report annually on its operations and to publish its balance sheet weekly. Similarly, under the financial reform law enacted after the financial crisis, we publicly report in detail on our lending programs and securities purchases, including the identities of borrowers and counterparties, amounts lent or purchased, and other information, such as collateral accepted. In late 2010, we posted detailed information on our public website about more than 21,000 individual credit and other transactions conducted to stabilize markets during the financial crisis. And, just last Friday, we posted the first in an ongoing series of quarterly reports providing a great deal of information on individual discount window loans and securities transactions. The Federal Reserve’s financial statement is audited by an independent, outside accounting firm, and an independent Inspector General has wide powers to review actions taken by the Board. Importantly, the Government Accountability Office (GAO) has the ability to–and does–oversee the efficiency and integrity of all of our operations, including our financial controls and governance.

While the GAO has access to all aspects of the Fed’s operations and is free to criticize or make recommendations, there is one important exception: monetary policymaking. In the 1970s, the Congress deliberately excluded monetary policy deliberations, decisions, and actions from the scope of GAO reviews. In doing so, the Congress carefully balanced the need for democratic accountability with the benefits that flow from keeping monetary policy free from short-term political pressures.

However, there have been recent proposals to expand the authority of the GAO over the Federal Reserve to include reviews of monetary policy decisions. Because the GAO is the investigative arm of the Congress and GAO reviews may be initiated at the request of members of the Congress, these reviews (or the prospect of reviews) of individual policy decisions could be seen, with good reason, as efforts to bring political pressure to bear on monetary policymakers. A perceived politicization of monetary policy would reduce public confidence in the ability of the Federal Reserve to make its policy decisions based strictly on what is good for the economy in the longer term. Balancing the need for accountability against the goal of insulating monetary policy from short-term political pressure is very important, and I believe that the Congress had it right in the 1970s when it explicitly chose to protect monetary policy decisionmaking from the possibility of politically motivated reviews.

Conclusion

In conclusion, I will simply note that these past few years have been a difficult time for the nation and the economy. For its part, the Federal Reserve has also been tested by unprecedented challenges. As we approach next year’s 100th anniversary of the signing of the Federal Reserve Act, however, I have great confidence in the institution. In particular, I would like to recognize the skill, professionalism, and dedication of the employees of the Federal Reserve System. They work tirelessly to serve the public interest and to promote prosperity for people and businesses across America. The Fed’s policy choices can always be debated, but the quality and commitment of the Federal Reserve as a public institution is second to none, and I am proud to lead it.Now that I’ve answered questions that I’ve posed to myself, I’d be happy to respond to yours.

-

S&P 500 +14.56% YTD

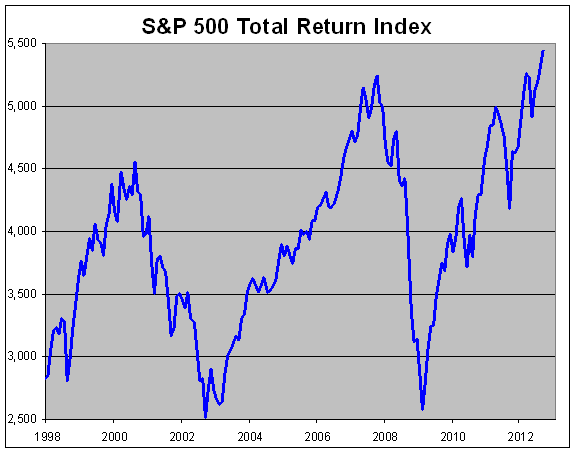

Posted by Eddy Elfenbein on October 1st, 2012 at 12:26 pmThe third quarter is now history. Let’s take a look at how the market is doing. Despite some fits, the S&P 500 is up 14.56% for the year. Add in dividends and we’re up 16.44%.

Here’s how the S&P 500’s total return index has performed over the past several years:

Over the last 12 years, the S&P 500 is up a grand total of 0.29% while the S&P 500 total return index is up 26.12%.

-

ISM = 51.5

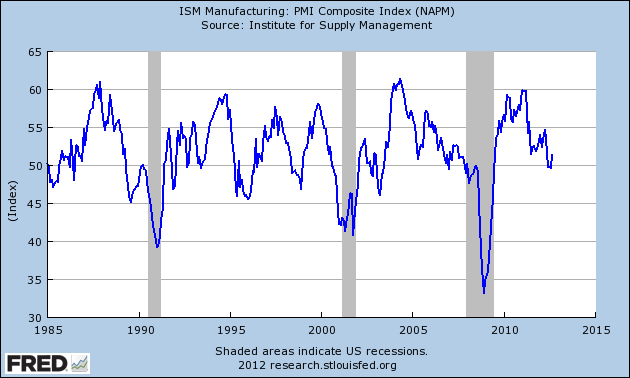

Posted by Eddy Elfenbein on October 1st, 2012 at 12:12 pmThe stock market is doing well today, especially financial stocks. JPMorgan Chase ($JPM) is up over 2% and Hudson City ($HCBK) finally broke $8 per share.

Today’s ISM reported rose to 51.5 which is the highest reading since May. The number for August was 49.6. Any number above 50 means the manufacturing is growing, and below 50 means contraction. Generally, recessions line up with ISM numbers below 45.

Traders are waiting to hear remarks from Ben Bernanke later today.

-

Morning News: October 1, 2012

Posted by Eddy Elfenbein on October 1st, 2012 at 5:17 amEuro Zone Sept Factory Data Flags “New Recession”

Credit Agricole In Talks To Hand Greek Bank To Alpha

Euro-Region Unemployment Rate Rises to Record 11.4% on Crisis

Europe Face Crisis October of Unrest as Troika Returns to Athens

Greek-Spanish Pension Split Illustrates Europe’s Dilemma

Analysts Cut Profit 52% as Europe Valuations Hit 2-Year High

Asian Factory Sector Struggles To Shake Off Euro Malaise

Oil Declines From One-Week High as China Manufacturing Weakens

Airlines’ Profit Outlook Recovering

Xstrata Board Recommends Glencore Deal

EADS Investor Lagardere Calls BAE Terms Unsatisfactory

Kodak Pulls Plug on Another Business

Student-Loan Default Rates Rise as Federal Scrutiny Grows

Jeff Carter: If Things Are So Bad, Why Won’t the Stock Market Break?

Jeff Miller: Weighing the Week Ahead: The Debate about Jobs

Be sure to follow me on Twitter.

-

Best Industries Over the Last Three Months

Posted by Eddy Elfenbein on September 28th, 2012 at 12:17 pmHere are the top-performing industries of the last three months. What’s interesting is how many seem related to QE3.

Industry Gain Dow Jones U.S. Platinum & Precious Metals Index 42.87% Dow Jones U.S. Mobile Telecommunications Index 29.12% Dow Jones U.S. Mortgage Finance Index 23.49% Dow Jones U.S. Internet Index 23.13% Dow Jones U.S. Gold Mining Index 21.88% Dow Jones U.S. Paper Index 21.40% Dow Jones U.S. Forestry & Paper Index 21.40% Dow Jones U.S. Consumer Electronics Index 20.18% Dow Jones U.S. Durable Household Products Index 16.87% Dow Jones U.S. Home Construction Index 16.78% CWS Market Review – September 28, 2012

Posted by Eddy Elfenbein on September 28th, 2012 at 7:23 amDon’t try to buy at the bottom and sell at the top. It can’t be done, except by liars. – Bernard Baruch

I’ve been warning investors that the stock market may be in for a rough patch, and we got a taste of that this week. On Thursday, the stock market finally snapped its five-day losing skid. Once again, the problems stem from Europe.

I know it sounds like a broken record but the economics of that continent seem terminally dysfunctional. There have been anti-austerity riots this week in Spain and Greece. Investors are beginning to realize that even if the euro survives, there will be a severe recession in Europe, and there’s a continent-wide rebellion against austerity policies.

In this week’s CWS Market Review, I want to take a closer at the economy and show you the best ways to protect yourself during the weeks ahead. The good news is that the worst of the euro crisis has already passed, but the road to recovery won’t be easy. Remember that the U.S. stock market bottomed out six months after Lehman Brothers went bankrupt.

The third quarter officially ends on Sunday, and we’ll soon get a look at Q3 earnings reports. Earnings season is Judgment Day for Wall Street; the good will be rewarded and the bad will be severely punished. I expect that our stocks on the Buy List will again demonstrate their superior attributes. Before we get to that, let’s dig into the surprising comeback of U.S. consumers.

U.S. Consumers Are Finally Waking Up

Putting Europe aside, not all the economic news has been dire. In fact, there’s been more evidence that U.S. consumers are finally waking up from their looong hibernation. This week, the Conference Board said that consumer confidence rose to a seven-month high. I was impressed to see that the expectations index rose as well.

This confirms previous evidence that there’s some emergent optimism in the air. Earlier this month, for example, Monster Worldwide, the job search website, said that there was an increase in online labor demand in August. And on Thursday, the Labor Department said that new claims for unemployment benefits dropped by 28,000 (though this number tends to bounce around a lot).

So what’s behind the new-found optimism of U.S. consumers? The main reason boils down to one word—housing. Economic recoveries in the U.S. have typically, but not always, been led by the housing sector. If you think about it, this makes a lot of sense. Not only is housing a major expense for consumers, but it also spills over into several other industries from retail (think Bed Bath & Beyond) to construction, transportation and finance.

The problem with this past recession is that we had so much overbuilding during the good times, that were was no need to build more homes. The homes built during the bubble weren’t going to disappear, so it’s taken us five years to work off the excess inventory. Only now are we getting the first clues that home prices are rising again. The CEO of Lennar ($LEN) recently said, “the housing market has stabilized, and the recovery is well underway.” Let’s hope so because higher home values cause a “wealth effect” which makes consumers happier and more willing to spend.

I’ll show you an example. Check out this chart. It shows the Homebuilders ETF ($XHB) in black along with the Retailers ETF ($XRT) in gold.

As you can see, the two ETFs have risen together. I’d say that they’re both lifting each other up. Homebuilders have done better because that sector had suffered more damage. I don’t think this trend will let up soon. A recent survey of retailers indicates that many plan to hire more holiday workers this year. Toys R Us just said they plan to hire 45,000 employees for this holiday season. Both Walmart ($WMT) and Kohl’s ($KSS) plan to add 50,000 workers for the holidays.

In the near-term, Wall Street will be focused on events in Europe and the election battle in America. Those events will most likely lead to greater volatility and a soggy market for stocks. The Spanish ETF ($EWP) recently gained 50% in just 52 days so some give back is probably due. But once the market gets past that, the signs are pointing to a strong year-end rally. Until that happens, investors need to play it safe.

Focus on High-Quality Dividends

The best way to protect yourself over the next few weeks is by making sure your portfolio has high-quality high-yield stocks. On our Buy List, this includes stocks like Reynolds American ($RAI), our tobacco stock. Reynolds is a classic consumer staples stock because their business is barely impacted by the twists and turns of the broader economy. RAI currently yields a very generous 5.42%. That’s the equivalent of 730 Dow points a year just in dividends. Reynolds is a buy up to $45.

I know some investors are skittish about investing in tobacco but there are several other top-notch stocks that pay big dividends. Thanks to its recent pullback, Nicholas Financial ($NICK) now yields 3.58%. Not only is NICK in good shape but I think the business has gotten stronger this year. Plus, the Fed’s willingness to keep short-term rates low is very good for NICK’s bottom line. Buy up to $15.

I highlighted Sysco ($SYY) in the CWS Market Review from three weeks ago, and the stock just broke out to a new 52-week high. The food service industry tends to be quite stable. Despite the rally for Sysco, the shares currently yield 3.46%. SYY is a buy up to $32.

AFLAC ($AFL) isn’t one of our higher yielders but I expect we’ll get another dividend increase when the company reports earnings next month. I’m not expecting a major increase. The quarterly dividend is currently 33 cents per share, and it will probably rise by one or two cents per share which means AFL may be yielding close to 3% right now. It’s frustrating that the market is treating AFL as if it’s a proxy for Europe. That’s simply not the case. AFL has dumped most of its lousy European holdings. This is a very undervalued stock. AFLAC is a strong buy up to $50 per share.

Another stock with an above-average dividend is Hudson City ($HCBK). The bank is the process of being taken over by M&T Bank ($MTB). Thanks to a rally for M&T, the buyout price for Hudson City has also increased. It will be a while before the deal is complete and management seems committed towards maintaining Hudson’s eight-cent-per-share quarterly dividend. At Thursday’s close, that works out to a yield of 4.07%. Hudson is a buy up to $8.

Thanks to its recent pullback, CA Technologies ($CA) now yields 3.86%. I’m looking forward to another good earnings report next month. CA Technologies is a good buy up to $30 per share.

Moog ($MOG-A) isn’t a dividend payer but I wanted to highlight it this week because it’s become one of the best values on our Buy List. Even though Moog gave us decent earnings guidance for 2013, and beat Wall Street’s earnings forecast in January, April and July, the stock hasn’t done much at all. Moog should be a $45 stock.

That’s all for now. Next week is the start of the fourth quarter, plus we’ll get the big jobs report on Friday. The summer is over so expect to see more volatility. Be sure to keep checking the blog for daily updates. I’ll have more market analysis for you in the next issue of CWS Market Review!

– Eddy

Morning News: September 28, 2012

Posted by Eddy Elfenbein on September 28th, 2012 at 6:33 amEuro Holds $1.29 On Spain Bailout Hopes

UK Seeks To Mend “Broken” Libor, Not Scrap It

For Sale, Cheap: The Cranes in Spain

Moody’s Downgrades Vietnam on Bank-Related Weaknesses

Oil Poised for Strongest Quarter This Year on Economic Optimism

Commodities Gain With European Stocks

Second-Quarter U.S. Growth Cut To 1.3%

Report: Federal Agencies Behind In Paying Taxes

Obama Economy Has Created Jobs as Payroll Revisions Raise Count

Sony to Buy Olympus Stake as Hirai Seeks Revival From Losses

RIM Defies Critics by Finding BlackBerry Sales Overseas

Heineken Wins Control Of Tiger Beer Maker; Focus Shifts To F&N

Tata Global Rallies As Starbucks Set To Open First Café

Cyber Attacks on U.S. Banks Expose Computer Vulnerability

Edward Harrison: Dennis Gartman On Commodities, Reserve Currencies And Gold

Joshua Brown: The Death of the College Bar Scene

Be sure to follow me on Twitter.

Q2 GDP Revised Down

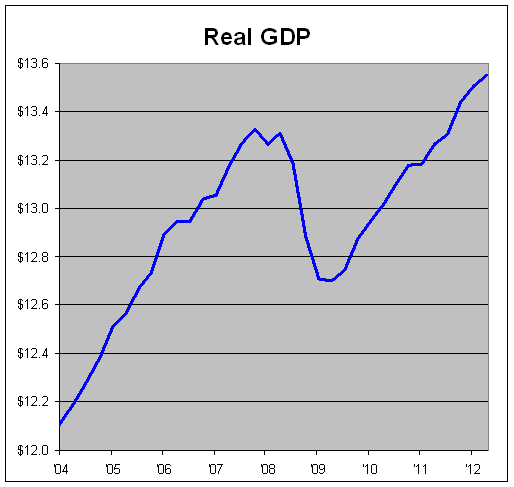

Posted by Eddy Elfenbein on September 27th, 2012 at 10:49 amThis morning, the government revised second-quarter GDP growth down to 1.3% from its initial estimate of 1.7%. For the first quarter, the economy grew by 2.0%.

Output was also revised down to reflect weaker rates of consumer and business spending than previously estimated. Outlays on residential construction export growth were also not as robust as had been previously estimated.

Economists polled by Reuters had expected second-quarter GDP growth would be unrevised at a 1.7 percent pace. The economy grew at a 2.0 percent pace in the January-March period.

The worst drought in half a century, which gripped large parts of the country in the summer, saw farm inventories dropping $5.3 billion in the second quarter after slipping $1 billion in the first three months of the year.

Data in hand for the third-quarter suggest little improvement in the growth pace, even as the housing market digs out of a six-year slump. Manufacturing, the pillar of the recovery from the 2007-09 recession is cooling, hurt by fears of tighter U.S. fiscal policy in January and slower global demand.

The GDP report also showed that after-tax corporate profits unexpectedly rose at a 2.2 percent rate instead of the previously reported 1.1 percent increase. After-tax profits fell 8.6 percent in the first quarter.

Morning News: September 27, 2012

Posted by Eddy Elfenbein on September 27th, 2012 at 6:32 amMarkets Falter in Europe Amid Protests on Austerity

Focus Turns to Spanish Budget Plan

Hollande Struggles to Match Sarkozy Budget-Gap Wins

China Stocks Jump Most in Three Weeks on Market Support Prospect

Yuan Snaps Two-Day Gain as PBOC Cuts Fixing Amid Growth Concern

Oil Recovers From Eight-Week Low After U.S. Inventories Dropped

Fracking Makes U.S. Surprise Energy Power

Gold Prices Crawl Back From Two-Week Lows

Banks Fail to Repel Cyber Threat

Beyond Wall St., Curbs on High-Speed Trades Proceed

Toyota Moves to Revamp Its Lexus Luxury Line

VW Says Some Carmakers May Go Bankrupt Without Assistance

H&M Profit Misses Analyst Estimates as Gap to Inditex Widens

Howard Lindzon: Google will be the First Trillion Dollar Company

Phil Pearlman: High Reactivity: Neurotic Market Continues

Be sure to follow me on Twitter.

The Importance of Extreme Events

Posted by Eddy Elfenbein on September 26th, 2012 at 11:05 pmOver the 116 years of its existence, the Dow Jones Industrial Average has risen by 4% or more in a single day 138 times, which works out to about once every ten months.

Now if we take the combined gain of these 138 days, it comes to more than six times the entire gain of the Dow over its entire 116 years.

In other words, most of the stock market’s gain has come on just 0.5% of the trading days. The other 99.5% of the time, the market is a net loser (this is just capital gain, not dividends).

Now let me stop for a second. While these stats are accurate, they’re slightly misleading. The problem happens with extreme events — at the far tails of the distribution. For example, the 138 days aren’t evenly spread out. Seventy of those days, a slim majority, came during the 1930s. There were only two 4% or more days between Pearl Harbor and JFK’s assassination.

The lesson is that finance tends to move in two speeds. The vast majority is slow and boring. Then, very suddenly, things get very, very dramatic.

-

-

Archives

- May 2025

- April 2025

- March 2025

- February 2025

- January 2025

- December 2024

- November 2024

- October 2024

- September 2024

- August 2024

- July 2024

- June 2024

- May 2024

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- July 2019

- June 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- May 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- July 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- March 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- July 2016

- June 2016

- May 2016

- April 2016

- March 2016

- February 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- July 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- April 2015

- March 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- December 2014

- November 2014

- October 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

- July 2014

- June 2014

- May 2014

- April 2014

- March 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- July 2013

- June 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- August 2012

- July 2012

- June 2012

- May 2012

- April 2012

- March 2012

- February 2012

- January 2012

- December 2011

- November 2011

- October 2011

- September 2011

- August 2011

- July 2011

- June 2011

- May 2011

- April 2011

- March 2011

- February 2011

- January 2011

- December 2010

- November 2010

- October 2010

- September 2010

- August 2010

- July 2010

- June 2010

- May 2010

- April 2010

- March 2010

- February 2010

- January 2010

- December 2009

- November 2009

- October 2009

- September 2009

- August 2009

- July 2009

- June 2009

- May 2009

- April 2009

- March 2009

- February 2009

- January 2009

- December 2008

- November 2008

- October 2008

- September 2008

- August 2008

- July 2008

- June 2008

- May 2008

- April 2008

- March 2008

- February 2008

- January 2008

- December 2007

- November 2007

- October 2007

- September 2007

- August 2007

- July 2007

- June 2007

- May 2007

- April 2007

- March 2007

- February 2007

- January 2007

- December 2006

- November 2006

- October 2006

- September 2006

- August 2006

- July 2006

- June 2006

- May 2006

- April 2006

- March 2006

- February 2006

- January 2006

- December 2005

- November 2005

- October 2005

- September 2005

- August 2005

- July 2005

Eddy Elfenbein is a Washington, DC-based speaker, portfolio manager and editor of the blog Crossing Wall Street. His

Eddy Elfenbein is a Washington, DC-based speaker, portfolio manager and editor of the blog Crossing Wall Street. His