-

The Derivatives Mess

Posted by Eddy Elfenbein on February 28th, 2006 at 10:02 amI meant to post this earlier. This WSJ article highlights the problems of the growth of derivatives on Wall Street.

Derivatives allow banks, companies and investors to transfer financial risk, much as homeowners buy insurance to shift the risk of repairing fire damage to an insurer. In the simplest form, Joe’s Manufacturing Inc. borrows $5 million at an interest rate that moves up and down with market rates, and then cuts a deal with Frank’s Investment Bank in which Joe promises to pay a fixed rate and Frank pays the variable rate.

The subspecies known as credit-default swaps allow banks that have lent money to, say, General Motors Corp. to shift risk of default to a risk-loving investor for a fee. As the market has evolved and drawn speculators, as well as banks looking to lay off risk, investors now place bets not only on individual firms, but on baskets of credits and on risks sliced and diced in increasingly complex ways.

You would think that Wall Street would have computerized this when the market started taking off a few years ago. But deals were, and often still are, done by telephone and fax. Detailed confirmations, important in avoiding nettlesome disputes later, weren’t completed. One firm confessed in June that it had 18,000 undocumented trades, several thousand of which had been languishing in the back office for more than 90 days. It wasn’t unusual.

That’s not all. One party to a two-party deal was routinely turning obligations over to a third party without telling the first one. It was as if you lent money to your brother-in-law and later learned that he had passed the debt to his deadbeat cousin without so much as an email. “When I realized how widespread that was, I was horrified,” says Gerald Corrigan, a former New York Fed president now at Goldman Sachs. “What it meant was that if you and I did a trade, and you assigned it without my knowing it, I thought you were my counterparty — but you weren’t.”

In LTCM’s case, each player knew the dimensions of its exposure; no one realized how exposed other firms were and how fragile LTCM’s strategy was. In the case of credit derivatives, the problem has been worse: Record-keeping, documentation and other practices have been so sloppy that no firm could be sure how much risk it was taking or with whom it had a deal. That’s a particularly embarrassing problem for an industry that has resisted regulation of derivatives by arguing that big firms would police each other.

Stocks, bonds and options traded on exchanges go through clearinghouses, which pick up the pieces when something goes awry with a trade. In this market, there’s no clearinghouse yet. Until recently, dealers didn’t even enter most credit-default-swap trades into a computer database to be sure both sides agreed on the terms.

Mr. Geithner, the Paul Revere of this story, began shouting about all of this before the end of his first year on the job. In an October 2004 speech, he noted that inadequate financial plumbing was “a potential source of uncertainty that can complicate how counterparties and markets respond in conditions of stress.” That’s central-bank speak for: The car is careening down the highway at 85 miles an hour and the lug nuts aren’t tight. If we hit a pothole, look out! -

Fourth-Quarter GDP

Posted by Eddy Elfenbein on February 28th, 2006 at 9:01 amGDP growth raised to 1.6%.

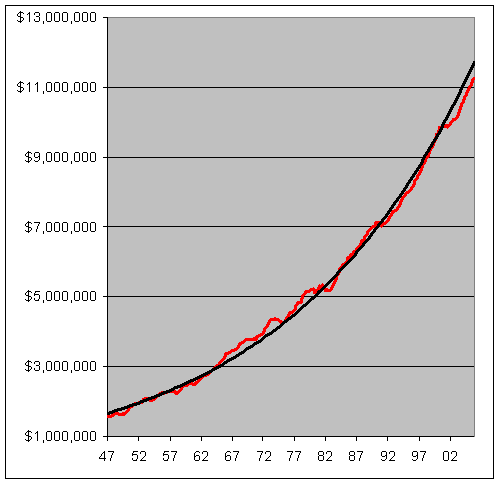

You wouldn’t know this from how people talk about the economy, but GDP growth is far more stable than most people realize. I often hear that the economy is “surging” or “crashing.” In reality, economic growth is a pretty stable trend that occasionally has some minor bumps.

Here’s a graph of real GDP growth over the last 60 years (red line) with a trend line line (black line).

Here’s a look at the trailing three-quarter growth rate of real GDP. I’m not sure why, but the nine-month view seems to work the best.

Notice how over the last 20 years, the economy has become far less cyclical. The peaks are getting lower, and the valleys are getting higher.

The Stalwart has speculated that as the overall economy has become more stable, the individual pieces have become more volatile. I think he’s right. Perhaps the price for collective security is the growth of constituent risk. -

PhytoMedical Technologies

Posted by Eddy Elfenbein on February 27th, 2006 at 10:06 pmDavid Phillips at 10Q Detective is unimpressed with PhytoMedical Technologies (PYTO.OB):

The 10Q Detective suggests that if PhytoMedical Technologies really wants to be taken seriously by the investment community—Perchance the Company could design a clinical trial that examines the safety and efficacy on the potential appetite-stimulating properties of a well-known plant-derived compound on the cachexia of cancer, HIV/AIDS symptomatology, and other wasting syndromes. This medicinal plant is called, cannabis sativa.

To be blunt (BA!)—given the Company’s current fundamental outlook—one would have to be smoking cannabis daily to even consider buying this stock.I guarantee you’ll never read that in a Merrill research report.

-

The Future of Food

Posted by Eddy Elfenbein on February 27th, 2006 at 7:59 pmSteven Milloy, the author of Junk Science Judo: Self-defense Against Health Scares and Scams, looks at the film “The Future of Food.”

Produced by Deborah Koons Garcia, the widow of the Grateful Dead’s Jerry Garcia, the movie’s overriding themes are allegations that biotech crops and food are unsafe and that a government-industry cabal is foisting dangerous products on an unwitting public.

Nothing could be farther from the truth.

Biotech crops and foods are among the most thoroughly tested products available. No other food crops in history have been so thoroughly tested and regulated. Before biotech products are marketed, they undergo years of safety testing including thousands of tests for potential toxicity, allergenicity and effects on non-target insects and the environment.

‘The Future of Food,’ for example, dredges up the 2000 scare involving a biotech corn that had not yet been approved for human consumption but that was detected in Taco Bell taco shells. A few consumers, egged on by anti-biotech activists, alleged the corn caused allergic reactions. But the movie glossed over the fact that the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention tested those consumers and reported there was no evidence that the biotech corn caused any allergic reaction in anyone.

Another long-buried myth excavated by Garcia was that biotechnology harms biodiversity. But so far it doesn’t appear to represent any greater risk to biodiversity than conventional agriculture and it actually seems to have some demonstrable beneficial impacts on biodiversity. An infamous biodiversity scare featured in the movie involved Monarch butterflies. The scare occurred during 1999-2000 when the media trumpeted alarmist results from two laboratory studies reporting that biotech corn might harm Monarch butterfly larvae. Subsequent field studies soon debunked the scare, reporting that Monarch larvae actually fared better inside biotech cornfields than in natural areas because of less pressure from predators. Needless to say, Monarchs in biotech cornfields also did much better than those in conventional cornfields sprayed with insecticides.

The movie claims that once biotech crops are planted, control over them is lost and they ‘contaminate’ non-biotech or organic crops. This is misleading since 100 percent purity has never been the reality in agriculture. Biological systems are dynamic environments, meaning that regardless of the method of production — conventional, organic or biotech — trace levels of other materials are always present in seed and grain. Since all commercial biotech traits are fully approved by U.S. regulatory agencies, their presence — in large amounts or trace amounts — is fully legal and safe.

With respect to organic farmers, the Department of Agriculture’s rules for organic products specifically say that the certification of organic products is process-based — meaning that if the proper processes are followed, the unintended presence of non-organic or biotech traits doesn’t disqualify the product from being labeled as ‘organic.’

To date, biotech crops haven’t harmed organic farmers. The coexistence of biotech, conventional and organic corn, soybean, and canola has been effectively working since 1995, when the first biotech crops were introduced. During that period, in fact, both biotech and organic farming have grown remarkably.

Garcia wants movie viewers to overlook the fact that U.S. regulators — including the Department of Agriculture, Environmental Protection Agency and the Food and Drug Administration — have established a robust framework and rigorous process for evaluating biotech product safety. Developers spend years generating data for one product to be submitted for approval.

A major take-home message of the movie is that consumers should demand labeling of biotech foods. But this would only increase the cost of food production while failing to provide any meaningful information to consumers. Biotech crops have been determined by regulators to be essentially equivalent to those of conventional crops. Corn is corn, in other words, no matter what anti-biotech activists would have us believe.

While emphasizing ‘scare,’ the movie overlooks biotechnology’s advantages. Biotech crops require less tilling. This reduces soil erosion; improves moisture retention; increases populations of soil microorganisms, earthworms and beneficial insects; and reduces sediment runoff into streams.

The movie mocks biotechnology’s potential value to the developing world, characterizing the argument as one designed for public relations use. But biotech crops such as ‘golden rice’ could help with the severe Vitamin A deficiency that afflicts hundreds of millions in Africa and Asia, ¬ including 500,000 children who lose their eyesight each year.

As pointed out by Greenpeace co-founder Patrick Moore, now a vociferous critic of the activist group, ‘Greenpeace activists threaten to rip the biotech rice out of the fields if farmers dare to plant it. They have done everything they can to discredit the scientists and the technology.

‘A commercial variety is now available for planting, but it will be at least five years before Golden Rice will be able to work its way through the Byzantine regulatory system that has been set up as a result of the activists’ campaign of misinformation and speculation,’ Moore said. ‘So the risk of not allowing farmers in Africa and Asia to grow Golden Rice is that another 2.5 million children will probably go blind.’

Garcia’s ‘The Future of Food’ is steeped in the Greens’ tragic campaign of misinformation. Many long-time anti-biotech campaigners helped her make the movie, in which not a balancing thought or counter-opinion is presented.

The ‘Future of Food’ purports to be a ‘documentary’ – a movie that sticks to the facts. It doesn’t. Hollywood will need a new Oscar category for this one. How about ‘crockumentary’? -

Lowe’s Vs. Home Depot

Posted by Eddy Elfenbein on February 27th, 2006 at 2:19 pmLowe’s reported great earnings today. Stephen D. Simpson looks at the battle between Lowe’s and Home Depot:

For those who would suggest that home improvement retailing ultimately has to be like The Highlander (“in the end, there can be only one…”), I’d observe that Wal-Mart and Target have profitably co-existed, as well as Office Depot, Staples, Wal-Mart’s Sam’s Club, and Costco.

All that said, it’s clearly true that Lowe’s is the pluckier and faster-growing of the two concepts. Sales in the fourth quarter climbed over 26% (nearly 8% on a comp-store basis), and earnings per share rose nearly 36%. Certainly those numbers outstrip what Home Depot managed to accomplish.

And there are certainly aspects of Lowe’s model that could be seen as working better than Home Depot’s. Lowe’s is generally thought to have better customer service, and the notion of trying out metro/urban stores is interesting.

By the way, Home Depot still has superior returns on capital. Home Depot also has a leg up in terms of international expansion and is moving aggressively into service businesses and MRO/industrial supply. So in this Fool’s opinion, comparing Home Depot and Lowe’s is no longer a fair straight-away comparison. -

Good Day Today

Posted by Eddy Elfenbein on February 27th, 2006 at 12:57 pmIf the market holds, the S&P 500 will close at a four-year high. The S&P 600 Small-Cap Index (^SML) and S&P 400 Mid-Cap Index (^MID) might close at new all-time highs. Plus, all 20 stocks on the Buy List are higher today.

-

Failure Never Felt So Good

Posted by Eddy Elfenbein on February 27th, 2006 at 11:21 amAttention corporate weasals. Don’t try to get anything past Michelle at Footnoted.org. It just ain’t gonna fly.

And speaking of former executives, there was also this little snippet buried in Morgan Stanley’s (MS) proxy, which was also filed late Friday. Again, while the broad-brush details were known, such as Philip Purcell’s $44 million bonus, the blow-by-blow was included in the proxy (do a search for CEO settlement to find it quickly). Among the pearls are that Purcell’s secretary, which the company has agreed to pay for as long as Purcell lives, will cost the company $1.8 million and that donations to Purcell’s favorite charities (again for life) will cost the company $2.9 million. And there’s another $3.1 million for benefits the company will provide the former executive, again for the rest of his life.

Indeed, failure never felt so good.And it pays well too.

Can you order Michelle’s book? But of course. I’ll be here when you get back. -

Owning a Toll Booth

Posted by Eddy Elfenbein on February 27th, 2006 at 11:15 amGroovyStocks on Intel (INTC):

According to Yahoo Finance, shares of Intel are now trading at 14.7 times trailing earnings and 14.1 times forward earnings with an EV/EBITDA ratio of 6.7. We think these are very reasonable multiples to pay for such a high quality company.

Sticking with Yahoo’s numbers, INTC has an operating margin of 31.1% and a profit margin of 22.3%. Return on assets is 15.7% and return on equity is 23.2%. The balance sheet has $12.8 billion in cash and $2.4 billion in debt, or over $10 billion in net cash. If you know another place where we can buy such high profitability and returns with balance sheet strength even half as good, please let us know!

Intel’s size gives it a huge competitive advantage. Here’s a quote from Columbia Business School professor Bruce Greenwald that sums the matter up:

“When Intel goes after the next generation chip, because it’s got some degree of customer captivity — which is crucial to scale advantages — Intel can expect, if it’s successful, to get 10 times as many customers as AMD. That means Intel can spend 10 times as much on developing and marketing the new chip. That’s the advantage of scale. So who’s going to win that race every time? Intel.” (Related Post)

We view owning Intel as owning a toll booth: (almost) every time somebody buys a computer you collect a fee. Sounds like a good business to us! -

Back Where We Started

Posted by Eddy Elfenbein on February 27th, 2006 at 10:34 amPrice chart of Intel (gold line) and Microsoft (black line) over the last eight years:

-

Confessions of an Economic Hit Man

Posted by Eddy Elfenbein on February 27th, 2006 at 9:44 amThe latest offering from the Grassy Knoll gang is “Confessions of an Economic Hit Man” by John Perkins. The book has become a bestseller. In it, he claims that the world is governed by big, evil corporations who use “a combination of bribes, assassins and seductive women to enslave the poorest countries.” In contrast, Sebastian Mallaby uses a combination of facts, reason and logic to expose this nonsense.

Perkins likes to say that of the world’s 100 biggest economies, 51 are companies. This old chestnut is based on a fallacious comparison of companies’ sales to countries’ gross domestic product: Whereas GDP measures the amount of value added in an economy, sales lump together a firm’s value-added with inputs bought in from suppliers. According to an apples-to-apples comparison done by the United Nations, just two of the world’s top 50 economies were companies in the year 2000. Of the top 100 economies, 29 were companies.

That may still sound like a lot, but remember that companies compete against each other. In the world as Perkins dreams it, the top 100 or so firms are joined in a shadowy conspiracy. But the reality is that Exxon Mobil schemes to undermine BP and Shell, and General Electric plots against Siemens and Hitachi. Countries don’t face a united corporatocracy. They play firms off against each other.

-

-

Archives

- June 2025

- May 2025

- April 2025

- March 2025

- February 2025

- January 2025

- December 2024

- November 2024

- October 2024

- September 2024

- August 2024

- July 2024

- June 2024

- May 2024

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- July 2019

- June 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- May 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- July 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- March 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- July 2016

- June 2016

- May 2016

- April 2016

- March 2016

- February 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- July 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- April 2015

- March 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- December 2014

- November 2014

- October 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

- July 2014

- June 2014

- May 2014

- April 2014

- March 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- July 2013

- June 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- August 2012

- July 2012

- June 2012

- May 2012

- April 2012

- March 2012

- February 2012

- January 2012

- December 2011

- November 2011

- October 2011

- September 2011

- August 2011

- July 2011

- June 2011

- May 2011

- April 2011

- March 2011

- February 2011

- January 2011

- December 2010

- November 2010

- October 2010

- September 2010

- August 2010

- July 2010

- June 2010

- May 2010

- April 2010

- March 2010

- February 2010

- January 2010

- December 2009

- November 2009

- October 2009

- September 2009

- August 2009

- July 2009

- June 2009

- May 2009

- April 2009

- March 2009

- February 2009

- January 2009

- December 2008

- November 2008

- October 2008

- September 2008

- August 2008

- July 2008

- June 2008

- May 2008

- April 2008

- March 2008

- February 2008

- January 2008

- December 2007

- November 2007

- October 2007

- September 2007

- August 2007

- July 2007

- June 2007

- May 2007

- April 2007

- March 2007

- February 2007

- January 2007

- December 2006

- November 2006

- October 2006

- September 2006

- August 2006

- July 2006

- June 2006

- May 2006

- April 2006

- March 2006

- February 2006

- January 2006

- December 2005

- November 2005

- October 2005

- September 2005

- August 2005

- July 2005

Eddy Elfenbein is a Washington, DC-based speaker, portfolio manager and editor of the blog Crossing Wall Street. His

Eddy Elfenbein is a Washington, DC-based speaker, portfolio manager and editor of the blog Crossing Wall Street. His