-

Raise the Price

Posted by Eddy Elfenbein on March 19th, 2008 at 8:08 amI really don’t see how Bear shareholders will approve the $2 deal. Apparently, I’m not alone. The stock is currently at $6 and it went as high as $8 yesterday.

Part of that the buying is being driven by BSC creditors (hedge funds, mainly) who don’t mind taking a small equity loss in exchange for a big debt gain—they just want the deal done. No one knows how much equity Bear truly has, but there’s around $300 billion of Bear Stearns bonds out there. If the whole mess goes to a bankruptcy court, then the stock holders go to the back of the line.

Of course, the debtor’s strategy could backfire if the price goes too high and JPM gets cold feet. Still, I doubt that would happen. As always, one shouldn’t fight the Fed.

I would say that the most likely outcome is that JP Morgan will sweeten the offer. To add some context, it’s really not that much for them. The company’s market value has already increased by $20 billion this week. The offer for Bear will cost them $236 million. What’s the big deal if they double or even triple it? Plus, it could win them some goodwill. Dimon is a very smart guy, and it might be a shrewd move to get out in front of what could become very unpleasant. If I were him, I’d meet with Joe Lewis, Legg Mason and other major BSC holders. He’s already won big. He can afford to be magnanimous.

On top of that, let’s not forget that JPM owns a gigantic call contract of whenever-$2s, and there’s also the building deal. Plus, it’s not unreasonable for the U.S. credit market to recover over the next few weeks. That could be a huge boon for BSC’s debt. To quote Michael Scott, it’s win-win-win. In fact, taxpayers could win as well.

I think we ought to move beyond the question of whether the Fed should be involved in—what I’ll call—a quasi-bailout. Instead, let’s look at the deal that was made, and it makes JPM look Putin-esque. The WSJ reminds us that it’s not uncommon for the government to make money off bailouts:During the 1995 peso crisis, the Clinton administration offered Mexico $20 billion in loans, with the country’s oil revenues as security. The International Monetary Fund offered another $18 billion. Critics condemned the loans as a bailout. In the end, Mexico didn’t require the entire amount, and the country’s finances recovered. The U.S. ended up making a profit on the interest payments.

The government also turned a profit from the Air Transportation Stabilization Board, an entity set up after the Sept. 11 attacks to support the airline industry. The board ultimately provided a total of $1.56 billion in loan guarantees to six carriers. The government earned just under $350 million from fees and stock sales, according to the Treasury Department.Last year, the Fed made a profit of $34 billion. It’s very possible that the central bank could make money on whatever they’ll get from Bear’s book. I still don’t understand who gets what. This seems to be a classic case of we don’t know what we don’t know. Perhaps the best move for the Fed is to hold the bonds to maturity.

-

Has Bill Miller Lost His Magic

Posted by Eddy Elfenbein on March 19th, 2008 at 7:42 amLegg Mason Value Trust (LMVTX) has badly lagged the market since the beginning of 2006. It has only gotten worse recently.

-

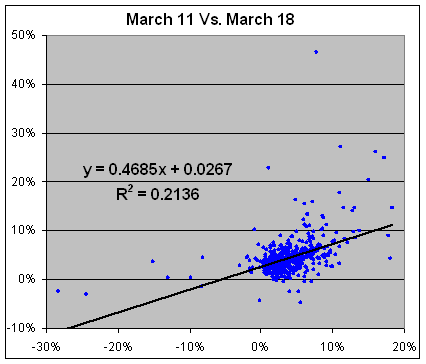

Today Compared with March 11

Posted by Eddy Elfenbein on March 18th, 2008 at 10:25 pmThe S&P 500 had another great day today. Today’s rally was more broad-based than the rally from last week.

Here’s a look at how the stocks in the S&P 500 fared. The X-axis is March 11, the Y-axis is today.

Here’s a spreadsheet listing how every stock in the S&P 500 did today. -

Ftizgerald Was Wrong

Posted by Eddy Elfenbein on March 18th, 2008 at 4:56 pmThere are second acts in American lives. Joe Weisenthal writes:

Google’s New Banking Partner?

Qatalyst. Release.“The launch of Qatalyst is an important development for the technology industry,” said Eric Schmidt, Chairman and CEO of Google. “Frank and his team bring unparalleled industry knowledge, a unique 25-year market perspective and candid, insightful judgment that CEOs greatly value on important strategic initiatives. I look forward to working with him again and am very enthusiastic about Qatalyst’s prospects for success.”

That Frank would be Frank Quattrone, continuing the comeback/American dream.

-

The Best Day in Five Years

Posted by Eddy Elfenbein on March 18th, 2008 at 4:29 pmRemember how I said that last Tuesday was the best day in five years. Well, I’ve changed my mind. I meant to say that this Tuesday was the best day in five years.

Date……………Gain

18-Mar-08…….4.24%

11-Mar-08…….3.71%

17-Mar-03…….3.54%

13-Mar-03…….3.45%

18-Sep-07…….2.92%

13-Nov-07…….2.91%

28-Nov-07…….2.86%

2-Apr-03……….2.61%

17-Aug-07…….2.46%

6-Aug-07………2.42%

21-Mar-03…….2.30%

16-Jun-03……..2.24%

1-Oct-03……….2.23% -

“Open the Kimono”

Posted by Eddy Elfenbein on March 18th, 2008 at 4:17 pmWow! I just heard Lehman’s CFO, Erin Callan, use the phrase “open the kimono” in a CNBC interview with Maria Bartiromo. By my math, that’s +1 to any company’s P/E.

By the way, Portfolio has just dubbed Ms. Callan as “Wall Street’s Most Powerful Woman.” I was waiting for Maria to ask about that. -

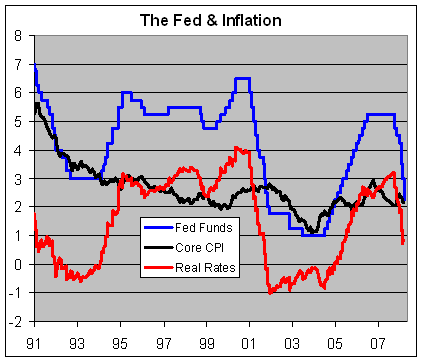

The Fed Cuts By 0.75%

Posted by Eddy Elfenbein on March 18th, 2008 at 2:19 pmThe Fed Funds rate is now down to 2.25%. Here’s the statement:

The Federal Open Market Committee decided today to lower its target for the federal funds rate 75 basis points to 2-1/4 percent.

Recent information indicates that the outlook for economic activity has weakened further. Growth in consumer spending has slowed and labor markets have softened. Financial markets remain under considerable stress, and the tightening of credit conditions and the deepening of the housing contraction are likely to weigh on economic growth over the next few quarters.

Inflation has been elevated, and some indicators of inflation expectations have risen. The Committee expects inflation to moderate in coming quarters, reflecting a projected leveling-out of energy and other commodity prices and an easing of pressures on resource utilization. Still, uncertainty about the inflation outlook has increased. It will be necessary to continue to monitor inflation developments carefully.

Today’s policy action, combined with those taken earlier, including measures to foster market liquidity, should help to promote moderate growth over time and to mitigate the risks to economic activity. However, downside risks to growth remain. The Committee will act in a timely manner as needed to promote sustainable economic growth and price stability.

Voting for the FOMC monetary policy action were: Ben S. Bernanke, Chairman; Timothy F. Geithner, Vice Chairman; Donald L. Kohn; Randall S. Kroszner; Frederic S. Mishkin; Sandra Pianalto; Gary H. Stern; and Kevin M. Warsh. Voting against were Richard W. Fisher and Charles I. Plosser, who preferred less aggressive action at this meeting.

In a related action, the Board of Governors unanimously approved a 75-basis-point decrease in the discount rate to 2-1/2 percent. In taking this action, the Board approved the requests submitted by the Boards of Directors of the Federal Reserve Banks of Boston, New York, and San Francisco.

-

FactSet Research Systems

Posted by Eddy Elfenbein on March 18th, 2008 at 2:07 pmThe popular belief seems to be that FactSet (FDS) is somehow a proxy for bad news in money management. The company’s results, however, continue to upset that thesis.

For Q2, FDS just reported a sales increase of 22% and adjusted EPS rose from 52 cents to 62 cents. Breaking down to the decimals, that’s an increase of 20.4%, and it beat the Street by two cents a share.

The company also said that Q3 revenues would be between $145 million to $149 million which is higher than the Street’s estimate. Best of all, that assumes no money from Bear Stearns (which is a safe assumption).

The shares are up over 20% but it’s really just making up for a lot of lost ground.

This is from the earnings call:Randy Hugen – Piper Jaffray Companies

Okay. And then, finally, was Bear Stearns a top 10 client?

Philip A. Hadley

No. Our largest client is less than 3% of our total ASV. And Bear Stearns was significantly less than 1%.

If you were to add some history to it, as similar in size as what Roberson Stevens was to us in the last cycle. It seems like every cycle one soldier goes down and that just happens to be the one in this cycle. Hopefully only one. -

The Pro Bailout Case

Posted by Eddy Elfenbein on March 18th, 2008 at 11:34 amIn Slate, Elizabeth Spiers argues in favor of the Bear bailout:

The alternative would have been to let Bear slide into a Chapter 11 bankruptcy, which would have happened quickly. Among other things, Moody’s, S&P, and Fitch all downgraded Bear on Friday, potentially forcing the firm to put up additional collateral to meet the requirements of a credit-default swap triggered by the downgrades—collateral it didn’t have. Bear notionally holds $13 trillion in derivatives contracts, and even if credit-default swaps were only a small fraction of that, any sort of credit event would have been catastrophic for both Bear and its buyers, the latter of whom would find themselves holding guarantees from a firm that was not in a position to guarantee anything.

Bear’s client assets would also have been frozen in the event of a bankruptcy, crippling not just the brokerage but many of the hedge funds that have collateral at the firm. (Fear of this happening is part of reason that the run on the bank—or run on the brokerage, rather—happened in the first place.) Taxpayers would have ended up footing the bill for assets that were federally insured, effectively a different kind of bailout. -

Inside the Demise of Bear Stearns

Posted by Eddy Elfenbein on March 18th, 2008 at 10:06 amThe Wall Street Journal has an excellent recap of the crisis that led to JPMorgan’s purchase of Bear Stearns. As this story initially broke, you got the feeling that this simply had to happen and there wasn’t much else policy makers could so. Yet, as I read the story, it becomes clear how arbitrary the whole mess was. I’m not sure it had to happen.

The more the sources stress the urgency, the more skeptical I become. Why was time so critical? If the problem is liquidity, then I would think that some breathing room could help out. Also, if tax dollars can be used to facilitate this deal, what’s to prevent them from propping up, say, Wal-Mart or General Motors?

My real enjoyment from these stories is figuring out how it was put together and seeing if you can see who the unnamed sources are. In every story, there are many motives. Naturally, anyone involved in the deal will want to speak with the WSJ as soon as possible to get their version of the story out.

The article begins:The past six days have shaken American capitalism.

Cute. That, of course, comes from John Reed’s famous book on the Russian Revolution, Ten Days that Shook the World. Reread that sentence again, but this time, take out the word “American.”

Now let’s start looking for clues:The mood changed daily, as did the apparent scope of the problem. On Friday, Treasury Secretary Henry Paulson thought markets would be calmed by the announcement that the Federal Reserve had agreed to help bail out Bear Stearns. President Bush gave a reassuring speech that day about the fundamental soundness of the U.S. economy. By Saturday, however, Mr. Paulson had become convinced that a definitive agreement to sell Bear Stearns had to be inked before markets opened yesterday.

Bear Stearns’s board of directors was whipsawed by the rapidly unfolding events, in particular by the pressure from Washington to clinch a deal, says one person familiar with their deliberations.

“We thought they gave us 28 days,” this person says, in reference to the terms of the Fed’s bailout financing. “Then they gave us 24 hours.”The “person” person is clearly a key source. Note that they’re playing up the sense of urgency. We’re being told that a deal simply had to be done before markets opened. This is the key goal of the story—explaining why a month delay was unacceptable.

The terms of the Bear Stearns sale contained some highly unusual features. For one, J.P. Morgan retains the option to purchase Bear’s valuable headquarters building in midtown Manhattan, even if Bear’s board recommends a rival offer (That’s a nice trick.). Also, the Fed has taken responsibility for $30 billion in hard-to-trade securities on Bear Stearns’s books, with potential for both profit and loss.

The question now looming over the transaction: Has the government set a precedent for propping up failing financial institutions at a time when its more traditional tools don’t appear to be working?Actually, there’s no question involved at all. Take that last sentence and delete the first word and the question mark.

Cutting interest rates — which the Fed is expected to do again today, by between a half percentage point and a full point — hasn’t yet done much to loosen capital markets gummed up by piles of bad debt.

Even though the transaction ultimately could leave taxpayers on the hook for losses, the political response so far has been fairly positive. “When you’re looking into the abyss, you don’t quibble over details,” said New York Democratic Senator Charles Schumer.Sorry Chuck, but I do. This is the closest relationship between government and private enterprise since Eliot Spitzer, although the roles now seem reversed.

Last Tuesday, we’re told, Wall Street started to turn against Bear.That same day, the market began turning on Bear Stearns. Phones were ringing off the hook at rival firms such as Goldman Sachs Group Inc., Morgan Stanley and Credit Suisse Group. Clients of those firms were growing worried about trades they had entered into with Bear Stearns — about whether Bear Stearns would be able to make good on its obligations. The clients asked the other investment banks whether they would be willing to take the clients’ places in the trades. But credit officers at Goldman, Morgan Stanley and others — worried themselves about Bear Stearns’s condition — began to say no.

At Bear Stearns, Chief Financial Officer Samuel Molinaro, along with company lawyers and Treasurer Robert Upton, were trying to make sense of the situation. They felt comfortable with their capital base of roughly $17 billion and were looking forward to reporting Bear Stearns’s first-quarter earnings, which had been respectable amid the market carnage.

One theory began developing internally: Hedge funds with short positions on Bear — bets that the company’s stock would fall — were trying to speed the decline by spreading negative rumors.Sounds like they were spreading the truth.

Bear Stearns’s hope was that the Fed would make a loan from its discount window to provide several weeks of breathing room. That, the firm hoped, would perhaps halt a run on the bank by allowing it to swap bonds for the cash necessary to return to customers.

The Fed’s standard preference in dealing with a troubled institution is to first seek a private-sector solution, such as a sale or financing agreement. But the possibility of a bankruptcy filing Friday morning created a hard deadline.

A trigger point was looming for Bear Stearns in the so-called repo market, where banks and securities firms extend and receive short-term loans, typically made overnight and backed by securities. At 7:30 a.m., Bear Stearns would have to begin paying back some of its billions of dollars in repo borrowings. If the firm didn’t repay the money on time, its creditors could start selling the collateral Bear had pledged to them. The implications went well beyond Bear Stearns: If other investors questioned the safety of loans they made in the repo market, they could start to withhold funds from other investment banks and companies.

The $4.5 trillion repo market isn’t a newfangled innovation like subprime-backed collateralized debt obligations. It is a decades-old, plain-vanilla market critical to the smooth functioning of capital markets. A default by a major counterparty would have been unprecedented, and could have had unpredictable consequences for the entire market.But why is the unprecedented action that was taken better than the unprecedented of allowing a default in the repo market? Obviously, no one likes a default, but the risk of a default is priced in. Now the market has to price in the participant’s political influence as well.

Federal Reserve Bank of New York President Timothy Geithner worked into the night, grabbing just two hours of sleep near the bank’s downtown Manhattan headquarters. His staff spent the night going over Bear’s books and talking to potential suitors including J. P. Morgan. The hard reality was that even interested buyers said they needed more time to go over the company.

The pace and complexity of events left Bear’s board of directors groping for answers. “It was a traumatic experience,” says one person who participated. Sleep deprivation set in, with some of the hundreds of attorneys and bankers sleeping only a few hours during a 72-hour sprint. Dress was casual, with neckties quickly shorn.A detail like “two hours of sleep” strongly suggests that Geithner was a source, as was “one person” from Bear’s board.

J.P. Morgan’s effort to buy Bear kicked into high gear on Friday afternoon, just hours after the big bank and the Fed had provided Bear with the 28-day lifeline. Steve Black, co-head of J.P. Morgan’s investment bank, returned early from vacation in the Caribbean, spearheading the bank’s efforts with his J.P. Morgan counterpart in London, Bill Winters.

Mr. Black’s role was pivotal. He was a longtime associate of J.P. Morgan Chief Executive James Dimon. And Mr. Black had a long relationship with Bear’s CEO, Mr. Schwartz, dating back to the 1970s, when the two were fraternity brothers at Duke University.There’s a nice little nugget. So the whole deal was started over a 30-year-old keg party. So I’m guessing Black was a source as well.

Wait a second, don’t Black and Schwartz really have the same name? Freaky….

On Saturday, the deal started to come together.That evening, Mr. Black got on the phone to Mr. Schwartz, Bear Stearns’s CEO. J.P. Morgan would be willing to buy Bear Stearns, subject to the conclusion of due diligence, he told Mr. Schwartz. The J.P. Morgan executives didn’t set a specific price, instead providing a dollars-per-share range, according to people familiar with the matter. At the high end was a figure in the low double digits, these people say.

So how did it go from the low double digits to the low single digits? It’s not really clear. JPMorgan started to get cold feet. Now for the climax:

Finally, they came to a conclusion. J.P. Morgan wouldn’t buy Bear Stearns on its own. The bank needed help before it would do the deal.

Mr. Paulson was frequently on the phone with Bear and J. P. Morgan executives, negotiating the details of the deal, the senior Treasury official said. Initially, Morgan wanted to pick off select parts of Bear, but Mr. Paulson insisted that it take the entire Bear portfolio, the official said.

This was no normal negotiation, says one person involved in the matter. Instead of two parties, there were three, this person explains, the third being the government. It is unclear what explicit requests were made by the Fed or Treasury. But the deal now in place has a number of features that are highly unusual, according to people who worked on the transaction.

In addition to its option to purchase Bear’s headquarters building, J.P. Morgan has the option to purchase just under 20% of Bear Stearns’s shares at a price of $2 each. That feature gives J.P. Morgan an ability to largely block a rival offer, says a person with knowledge of the contract.

The deal also is highly “locked up,” meaning that J.P. Morgan cannot walk, even if there is a heavy deterioration in Bear’s business or future prospects. Bear Stearns holders can, of course, vote the deal down. But the effect that would have on J.P. Morgan’s ongoing managerial oversight and the Fed’s guarantees is largely unknown.

“We’re in hyperspace,” says one person who worked on the deal. All these matters are very likely to be litigated in court eventually, this person adds.

The Fed spent the weekend putting together a plan to be announced Sunday evening, regardless of the outcome of Bear’s negotiations, that would enable all Wall Street banks to borrow from the central bank. Mr. Bernanke called the Fed’s five governors together for a vote Sunday afternoon. All five voted in favor, using for the second time since Friday the Fed’s authority to lend to nonbanks.

The steps were announced at the same time the Fed agreed to lend $30 billion to J.P. Morgan to complete its acquisition of Bear Stearns. The loans will be secured solely by difficult-to-value assets inherited from Bear Stearns. If the assets decline in value, the Fed — and therefore the U.S. taxpayer — will bear the cost.

-

-

Archives

- May 2025

- April 2025

- March 2025

- February 2025

- January 2025

- December 2024

- November 2024

- October 2024

- September 2024

- August 2024

- July 2024

- June 2024

- May 2024

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- July 2019

- June 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- May 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- July 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- March 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- July 2016

- June 2016

- May 2016

- April 2016

- March 2016

- February 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- July 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- April 2015

- March 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- December 2014

- November 2014

- October 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

- July 2014

- June 2014

- May 2014

- April 2014

- March 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- July 2013

- June 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- August 2012

- July 2012

- June 2012

- May 2012

- April 2012

- March 2012

- February 2012

- January 2012

- December 2011

- November 2011

- October 2011

- September 2011

- August 2011

- July 2011

- June 2011

- May 2011

- April 2011

- March 2011

- February 2011

- January 2011

- December 2010

- November 2010

- October 2010

- September 2010

- August 2010

- July 2010

- June 2010

- May 2010

- April 2010

- March 2010

- February 2010

- January 2010

- December 2009

- November 2009

- October 2009

- September 2009

- August 2009

- July 2009

- June 2009

- May 2009

- April 2009

- March 2009

- February 2009

- January 2009

- December 2008

- November 2008

- October 2008

- September 2008

- August 2008

- July 2008

- June 2008

- May 2008

- April 2008

- March 2008

- February 2008

- January 2008

- December 2007

- November 2007

- October 2007

- September 2007

- August 2007

- July 2007

- June 2007

- May 2007

- April 2007

- March 2007

- February 2007

- January 2007

- December 2006

- November 2006

- October 2006

- September 2006

- August 2006

- July 2006

- June 2006

- May 2006

- April 2006

- March 2006

- February 2006

- January 2006

- December 2005

- November 2005

- October 2005

- September 2005

- August 2005

- July 2005

Eddy Elfenbein is a Washington, DC-based speaker, portfolio manager and editor of the blog Crossing Wall Street. His

Eddy Elfenbein is a Washington, DC-based speaker, portfolio manager and editor of the blog Crossing Wall Street. His